Haiku: The Overlooked Poetry

An appreciation of the haiku as an artform

The haiku is a poetic form that is light to handle but difficult to master. Underappreciated for its simplicity, it is sometimes thought of as the poet’s hors d'oeuvre: that is, a bite-sized piece about some minor observation used only as an entrance or complement to real writing.

This is an unfair characterisation; one mustn’t confuse ease of reading with ease of writing. Taken a step further, one should not approach haiku as something easy to read.

As a form of poetry, the haiku is peerless in its ability to seize the moment. In few words, it captures the ephemeral: it freezes a thought so that it shows itself differently from many facets. The true mark of literary wit, they say, is in brevity, and this is the haiku’s greatest strength and challenge.

But to understand its virtues, one must see it in its full, cultural context.

The History of Haiku

This genre finds its origins in Japan as a sort of prologue to the longer-form renga. By the seventeenth century, Japanese poets began to work in short, concise stanzas that would come to stand on their own as individual haiku, known then as hokku. As with most works of the time, the form emphasized the natural and often couched its meaning in seasonal imagery.

In the West, haiku are infamous for following a strict, three-line structure with a syllable count of 5-7-5. Traditional Japanese haiku divide their words into on, a linguistic element not unlike the syllable but distinct in its own right. Due to this minor point of difference, there is some disagreement on whether a 17-syllable count in English makes for a culturally faithful haiku. Modern haikuists even use this argument to occasionally reorder the 5-7-5 structure to something more like 4-6-4 or even 3-6-3.

But lesser-known of the haiku is the incorporation of the kigo and kireji. Kigo in this instance refers to a word that identifies the season of the haiku, affording the poet a greater freedom of words, while the kireji – or the “cutting word” – creates a kind of poetic dichotomy by juxtaposing themes or images in the piece.

The combination of these poetic tools allows for a clearly-defined mood within the poem as well as a reflective turn-of-attention. Both of these are necessary components of traditional haiku.

“Oh, tranquillity!

Penetrating the very rock,

A cicada’s voice.”

– Matsuo Bashō

In this example, we are confronted by the breaking of the quiet – the tranquillity of the moment – by the hum of a cicada. But it’s a contemplative action, “penetrating the very rock”, meditative in its harshness. The separation of the lines leaves some ambiguity as to what penetrates the rock: the quiet or the interruption. And these two elements are cleanly cut by this action upon the rock, creating a juxtaposition of two opposites.

Mono no Aware

Parallel to the innovation of standalone haiku was that of the philosophical concept mono no aware.

Pinning down a precise meaning to this phrase is difficult, but it is understood in English most simply as an appreciation for the transience of things. This expression invokes a sense of pleasant, passing surprise: one might think of the flitting of a butterfly or the scintillation of a rainbow looming wide over a wet city. One could also imagine the shape of water or the roll of thunder as captured in their infinitesimal moments.

In its essence, mono no aware conveys the notion that things are precious because they do not last.

This concept pervades all aspects of Japanese culture, from their art and music down to their written forms. But the haiku typifies this above all by distilling the complex, beautiful forms of nature into a three-line stanza as simple as a photograph. In few words, it captures a moment that is as beautiful as it is impermanent: and we, the readers, come to understand that they are beautiful because they are impermanent.

“Light of the moon

Moves west, flowers' shadows

Creep eastward.”

– Yosa Buson

Here, the reader is brought into the powerful image of the moon in its travels across the sky. Flowers below, in a meadow or on the bough of a tree, cast shadows in what can be understood to be the clear, silver light of a full moon. We see here captured a moment that, while magnificent in its imagery, is also fleeting and unreplicable.

As readers, we are invited to take in these moments in our own lives as they come.

Famous Haikuists Through the Ages

Matsuo Bashō

One could not possibly write an article about the haiku without mentioning master Matsuo Bashō, a man of Edo Japan, born halfway through the 17th century. He is considered one of the greatest haiku writers in history and is credited with inventing the form itself.

In one of his earliest works, Bashō writes:

“On a withered branch

A crow is perched

An autumn evening”

This single poem has been dissected by haiku experts and poetry enthusiasts alike for centuries. Its meanings are specific to its time: the crow was revered by the feudal Japanese as a messenger of heaven.

But Bashō, ever the artist, believed that the human experience is best expressed through metaphor. We imagine what he might have worn in the autumns of Edo: a black robe, flowing and warm for cooling nights, which might have called to mind the wings of a great crow. Perhaps he was describing some loneliness in himself as he passed the short nights of autumn alone, or perhaps the turn of the season inspired the observation of heaven’s messenger alighting upon a branch.

Whatever the inspiration, the interpretations are endless, and this haiku is truly timeless.

Jack Kerouac

Many Western writers have taken to the haiku for its simplicity and observational power.

Kerouac, an American writer of French-Canadian descent, sought to reinvent the haiku and often broke its rules to that end. But his more traditional haiku can be described as purely observational, with little of the mono no aware that inhabited the first forms.

Here, Jack Kerouac observes:

“Nightfall,

boy smashing dandelions

with a stick.”

There’s certainly something to be said for the human condition, here, but it doesn’t speak to our greatness. Kerouac’s works are known for their spontaneity, and as such, they often capture sorry, faithless moments as much as the uplift and wonder of more traditional haiku. In him you will find a varied, nuanced soul, and a fascinating read.

Elizabeth Searle Lamb

Another American poetess who was once described as the “First Lady of American Haiku,” Elizabeth Searle Lamb is a literary giant all her own. Like Kerouac, her haiku forms tend more towards the observational, but has a habit of giving voice to inanimate objects. The focus in much of her work lies in the visual arts, with many of her poems dedicated to sculptures and paintings by famous artists.

She writes of Picasso,

“Picasso’s ‘Bust of Sylvette’

not knowing it is a new year

smiles in the same old way”

In this poem, she captures the timelessness of the sculpture itself, but also speaks to a kind of endearing ignorance in it.

One interpretation is that it acts as a commentary on the role of the woman in 1970’s America, an era which saw great social changes to the concept of gender roles; that, as an object, the Bust of Sylvette shows a woman who seems to be unaware of the change of the times, but continues smiling despite her objectification.

Haiku in Other Forms

The haiku has captivated the world with its ability to crystallize a scene. Like photography, it allows the briefest of moments to live on long after they’re over.

While the idea behind the haiku has evolved in form, its spirit remains intact.

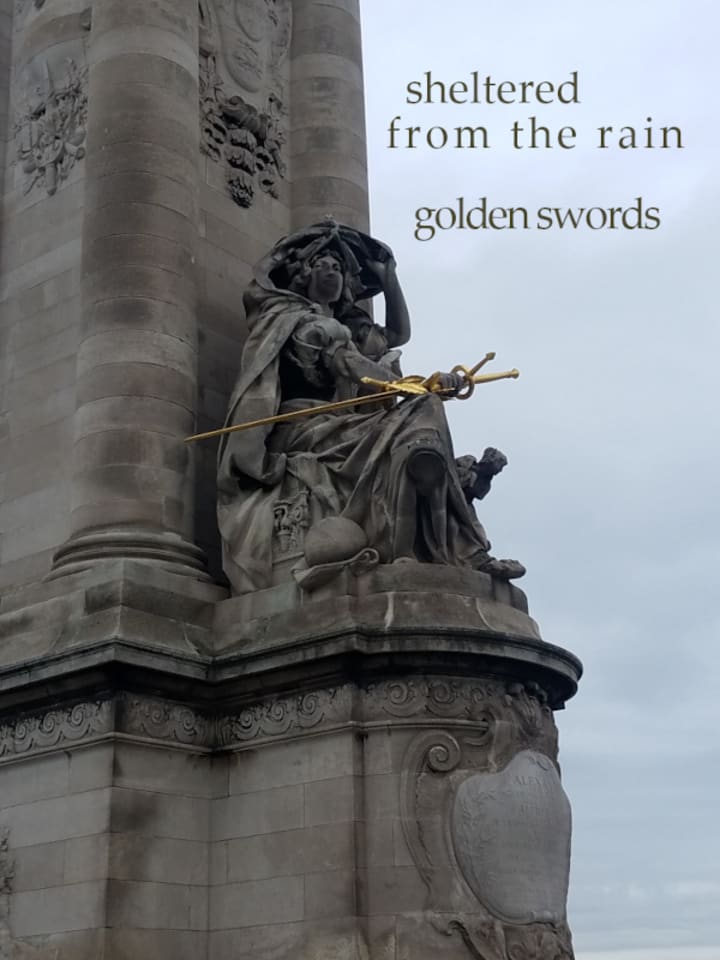

As a fantastic pairing to photography, the haiku appears in other forms such as the sixku, invented by poet-photographer Cendrine Marrouat. In this genre, one is limited to an expression of just six words inspired by and superimposed over a photograph.

Here, I try my hand at Marrouat’s form. The expression is simple, but powerful; it contrasts cover from the coming storm – a vulnerability – with golden weapons, a symbol of victory or power.

To find out more about the sixku and its rules, check out its page.

The Vardhaku

The haiku as a written form is flexible and easy-to-adapt to tastes and moods. So it evolves further.

I have had the pleasure of working with Cendrine Marrouat towards crafting a new kind of poetic form that builds on the idea of the haiku. We spent long hours agonizing over the name of it, but we always knew what we wanted it to accomplish.

From the first, we wanted to create a kind of haiku form that encouraged a feeling of growth or resolution from some initial problem. We knew vaguely that we wanted it to be 5 lines, with each line growing in either word or syllable count. The final line, we agreed, would succinctly demonstrate a movement away from the problem, either by resolution, personal growth, or self-reflection.

After consulting rather conflicting etymological records and pingponging several word roots between us, we arrived at the vardhaku, which consists of the elements vardha- (Sanskrit vardhana: growth, increase, gladdening) and -ku, which designates the form as a simple, Japanese poem.

So we tried a couple on for size:

“This

the long hours

the long forgotten

embrace of our yesterday:

we are still swimming in a deep ocean of love.”

©2021 Cendrine Marrouat. All rights reserved.

“Writer’s block:

a clipping of wings

on words to lose their flight,

that in trees they dwell with no descent

but the writer climbed that trunk and found a nest.”

©2021 Justin Smith. All rights reserved.

– and we found a form which visually conveys a sense of growth while also offering relief from the opening trouble.

If you’d like to learn more about this form and its specific rules, please head over to Cendrine’s page. You’ll also find some fantastic work from her in both poetry and photography, so be sure to check her out!

In a world of instant sharing and limited characters, one might find it surprising that such shorthand, observational poetry is often overlooked – but so it is.

The haiku is a timeless, thoughtful form that offers much while saying little. With a simple composition, it often holds complex concepts that can be interpreted according to one's experiences. As a discipline, it can actually assist writers to express themselves more succinctly.

My recent fascination with haiku stems from my relationship with the aforementioned Cendrine Marrouat, who sees the beauty of the world in its mundanity. She's shown me that the haiku is a small pen that draws big shapes in the heart, and for that I am grateful.

I encourage anyone with a fascination with nature and a wonder of the world to try any of these forms. If you do, please reach out to me at @ismsofallsorts on Twitter and share them with me.

About the Creator

Justin

An American writer with a flair for dark fiction. Currently living in Brisbane, Australia.

Chocolate, wine, and coffee are all acceptable tribute.

Twitter: @ismsofallsorts

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.