Dream Country

A historical fiction short story about the artist Chiura Obata and his departure from the Topaz Internment Camp

Author's note: During World War II, people of Japanese origin were placed in internment camps across the American West. One of those people was the great sumi-e artist Chiura Obata. The following is a work of historical fiction depicting his time in the Topaz Internment Camp, including a violent assault he suffered at the hands of a fellow internee - likely because Obata was seen as an American apologist. Though I have endeavored to make it as factually accurate as possible, I have taken some small liberties. The work was informed by Obata's art, his writing, his family's memories of this time period, the documentary work of his fellow internees, and government records.

1. April 4, 1943. Topaz.

Under my cheek, a salty pool has collected in the ancient lakebed. Have the waters returned to the delta? I imagine a flood, channeling swiftly from the top of Topaz Mountain. The dust, fine as lime and charcoal, churned into a thick suck of mud. The buried mollusk shells regenerating their sticky inhabitants and crawling over the barracks. I extend my tongue to taste the waters, but there is no cool relief. Just a gritty mouthful of iron.

I blink. My right eye responds. My left eye – my left –

There is no flood. I lie in a pool of my own blood, and the thirsty chalk floor of Topaz drinks it.

I stand, haltingly, my face numb and pulsing. Half-blind, blood flowing over my robe, I lurch through Block Five, counting numbly. I am at the showers. I must cross four buildings east, nine north. I must hope my attackers have fled, left me for dead on the desert floor. I must hope Haruko is safe, waiting for me, worrying by the cherry glow of the stove.

Somewhere I have lost my geta. My bare feet feel me through the powdery dark in a shuffle. I trace along the sides of our hobbled houses. 12 to a barrack. I count, keeping track by the muffled sounds of their inhabitants. The scream of a newborn by building four: the Ishikawa baby, not yet two weeks old and wracked with colic. A muffled argument by building eight: Tane Hakayama lecturing her troublesome son. I grow closer, I think.

I reach 9d, listing from side to side. Is that a whiff of juniper from the stunted trees Haruko has planted at our door? I call for her, “Mama!” But what comes out is nothing but a dry wheeze. I cough and stumble, the rock path catching my weaving feet and pulling me back to the ground. I lie on my back. I squint at the sky.

My vision shudders. There is no moon tonight. The hulk of Topaz Mountain is only an absence of stars. Fear clouds my throat, choking as a dust storm. My country has shunned me, my people have turned from me, even Great Nature is hidden from my blurry eyes.

What is left to salvage?

“Papa? Papa!” Haruko’s voice from mere meters away. Lamplight breaks the caul of blood and confusion. “Chiura! What have they done to you?”

2. 1890. Sendai.

A blank piece of paper lies before me. Beside it is an old brush and a palette of watery ink. “Give me a circle,” Rokuichi tells me, “very small.” I pick up the brush clumsily and soak its worn sheep-hair bristle in the dish, then bring it to the surface of the page. A circle appears, even and proportional. I blow at the sheen of the fresh ink. “Again. No elbows this time. Only lazy painters use elbows.”

I smirk. Rokuichi uses his elbows sometimes. I try, but my arm shakes and the circle wobbles. For the next, I return my elbow back to the table. A shock of sharp pain on the back of my arm jerks my hand across the page. I shout in surprise and the brush skids into a long smudge. Rokuichi, rapping my arms with a thin stick: “I said no elbows. Again.”

I, a small boy at the edge of the Natori River. Sketching brave men and mountains with my fingers in the mud. Away from Rokuichi, the hand is steady even as thick red welts swell. Someone should tell me: In seven years, you will run. It will get worse. And then it will get better.

3. April 5, 1943. Topaz.

I wake to a foreign feeling of warmth, the luxury of two blankets wrapped around me. I can still sense the powdery sift of alkaline dust in the air, but it is cut by a sharp tang of antiseptic. I made it to the hospital, then. My face no longer feels numb. The whole left of my head feels lumpy and thick. I attempt to open my eyes and a hot noose of panic descends. Like before, my left eye will not respond. My right eye is open, but still I see nothing. Blurs of color swim before me, dust-clouded. I have lost my sight. If I cannot see, how will I paint? I blink. Again.

In long seconds, a picture comes into focus. Eddies of nurses in striped aprons swirl unhurriedly around the long rows of beds. They scuff and jump over the pine-board floor, warped already from just one year of Topaz’s extreme temperature shifts. At my bedside table, a small vase carved from desertwood sits, stuffed with a harmonious arrangement of cramped blossoms and long, reaching sticks. Haruko has been busy.

And at the foot of my bed the artist herself sits, knitting needles in hand. Haruko roils knits and purls too tightly, an unusually lumpy sock emerging from the chaos.

Her mouth twitches back and forth, as though she chastises the sock for being so willfully ugly. I attempt to rise and can only rustle the blankets before falling weakly back. I attempt to speak, but dust catches in my throat and I cough instead. The sharp movement pounds pain into my injuries anew, like birds startled into an aching flight.

She stops knitting but does not look up. “So,” she says in tight, clipped Japanese. “Is it enough now? Or will they have to kill you next time?” Her voice like steel. “I told you, we should never have come here. We could have left. We could have –” She trails off. “Gyo is waiting for us in St. Louis. These aren’t our people anymore, Chiura.”

Experimentally, I curl my fingers. Stiff, but workable. “Bring me my sketchbook, Haruko.”

“The doctors say – ”

“My pens and brushes, too.” There is a silence, pregnant with disapproval. She finally looks at me. I watch her eyes worry my forehead, the swollen flesh sitting heavily over my left eye. She will do as I have asked. I can tell from the gentle shake of her head even as she chides me.

“Art will not heal you. It will not heal this camp, either. You did what you could.” She collects her knitting and leaves my bedside.

If I had felt better, perhaps I would have argued with her. But it is an old argument, one we may never settle. Perhaps it is by merit of our chosen art forms: Haruko’s ikebana, glorious and stirring, is ephemeral. Petals will fall and greenery will rot.

But my paintings stay. My ink settles the storms of Yosemite. It stills the endless sway of mile-high pines. It preserves the mist of the mornings. It will save us, too.

4. 1899. Tokyo.

Murata-sensei and I, sitting in a teahouse. The evening wakes around us, men spilling out of their offices and over the narrow streets like leaves in a stream. “So, Zoroku. You will be shown at the exhibition.” Relief flows through me. “They have, however, asked me what your name is.” I rub at my forehead. I had not thought this far, had only hoped my painting would be accepted.

“Can it not be Murata?” I ask. He smiles wryly, shaking his head.

“That would be disingenuous. When you came to me, you were already a sumi-e artist. I will not claim to be your first teacher.” He stands. “They do not need an answer until tomorrow. Take the night.”

I do as he says. I walk the busy docks of Tokyo and think of Sendai. The thousands of bays I sketched, away from Rokuichi’s demands of requital. The grumbling sway of loose rocks in the tide, the thin curls of white sand, the distant mountain crests. I smile to think of the days I spent in the island’s little inlets, learning from their ever-changing shores.

I will not take Rokuichi’s name, even if he was my first teacher.

I learned from the bays of Sendai. Chi-ura. Thousand Bays.

5. April 6, 1943. Topaz.

It is midday. One of the nurses has propped me up against a pillow, but through its thin pad I can still feel the bed’s metal bars dig into my back. In my lap, my paper and a pen. Ready for my work.

Haruko dropped them at the front while I slept. I am sleeping too much, I think. Dr. Goto brought them to me with a warning. “Obata-san, you have undergone extensive trauma. You must rest your head, do not try to work so hard.”

“It will not hurt me to move my hand.”

“You most definitely have a concussion. I can only speculate you have some swelling in your brain, as well. Your hand is not the issue – I worry about your brain, and your eye.”

“I will be very careful with this strenuous activity, Goto-sensei.” At this, he laughed.

“If you are still calling me sensei after I have lost my license, perhaps you were hit even harder than I thought. Go on, Obata, sketch to your heart’s content. But you will not convince me to sketch at the window yet – you will stay in this bed. Understood?”

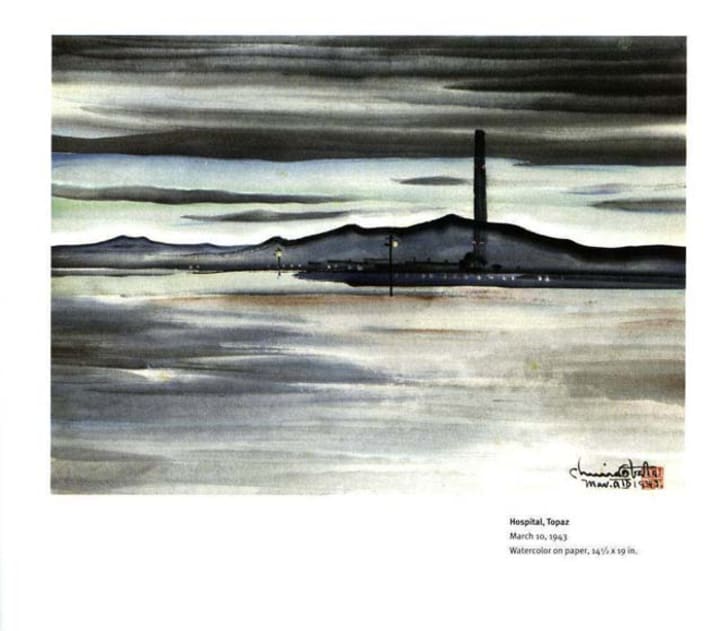

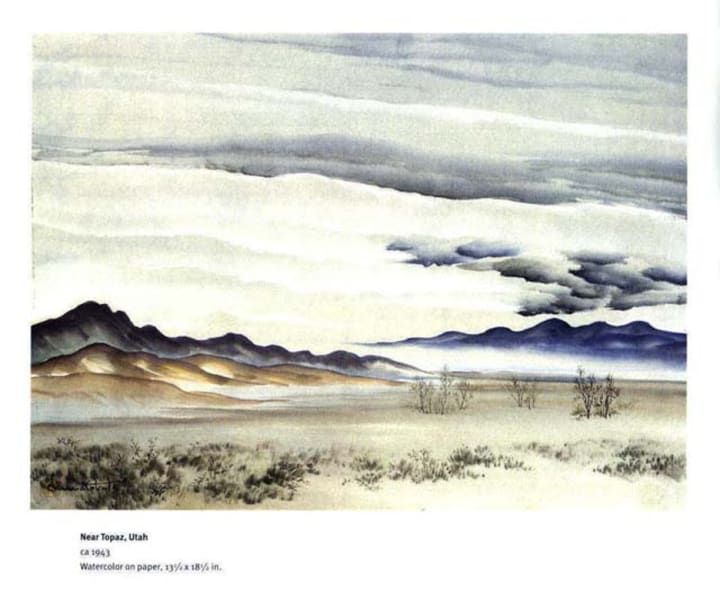

So. If I cannot be brought to the window – so temptingly close, not even 6 meters away, with the golden crest of Mt. Topaz glinting beyond the dusty pane – then what is near must suffice.

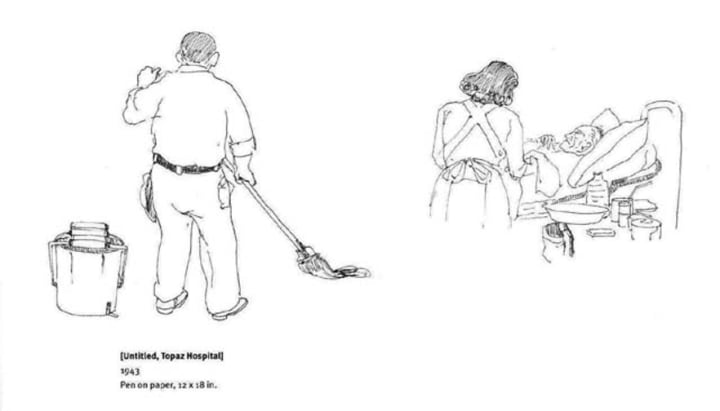

The beds closest to me are rumpled, unmade but uninhabited. The room is quiet with some small, repetitive utterances: the squeak of the janitor’s mop on the floorboards, the restless flip of another patient’s copy of the Topaz Times, the nurse’s murmurs as she completes her rounds. It strikes me suddenly, how isolated I am in my pain. My bed is an island in a storm of rumors.

No matter. I will sketch their backs. The janitor’s leaking bucket, his sagging pants. The crisscross of the nurse’s apron straps as she bathes an old woman with a rag. The craggy wrinkles of the old woman’s face, cracked and weathered like the desert floor. I study her, squinting my one good eye as my pen runs across the page. I look over my work. Sigh in disgust. The sketches are amateur. Uninspired.

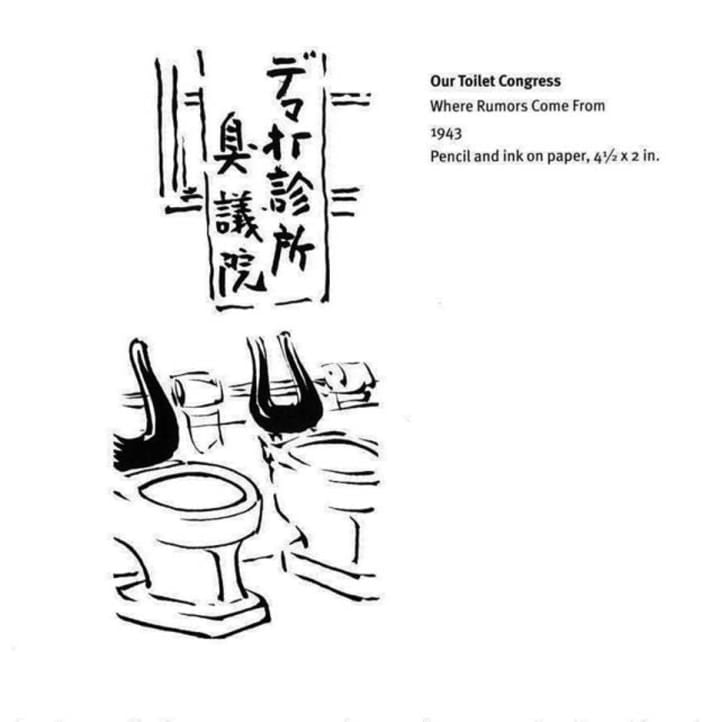

I throw the pen down, leaving the old woman’s bed unfinished. Anger runs through me deep, like an undercurrent. I dive in and allow it to swell. All I had done was for the good of the camp, for my fellow internees. I just wanted to give them something beautiful. They looked around and saw only the bad. The horse stalls they shoved us in back at Tanforan. The bathrooms, with their doorless toilets and stagnant chlorine puddles. The neverending dust that clogged our lungs and wormed its way through the cracks of our shoddily built walls.

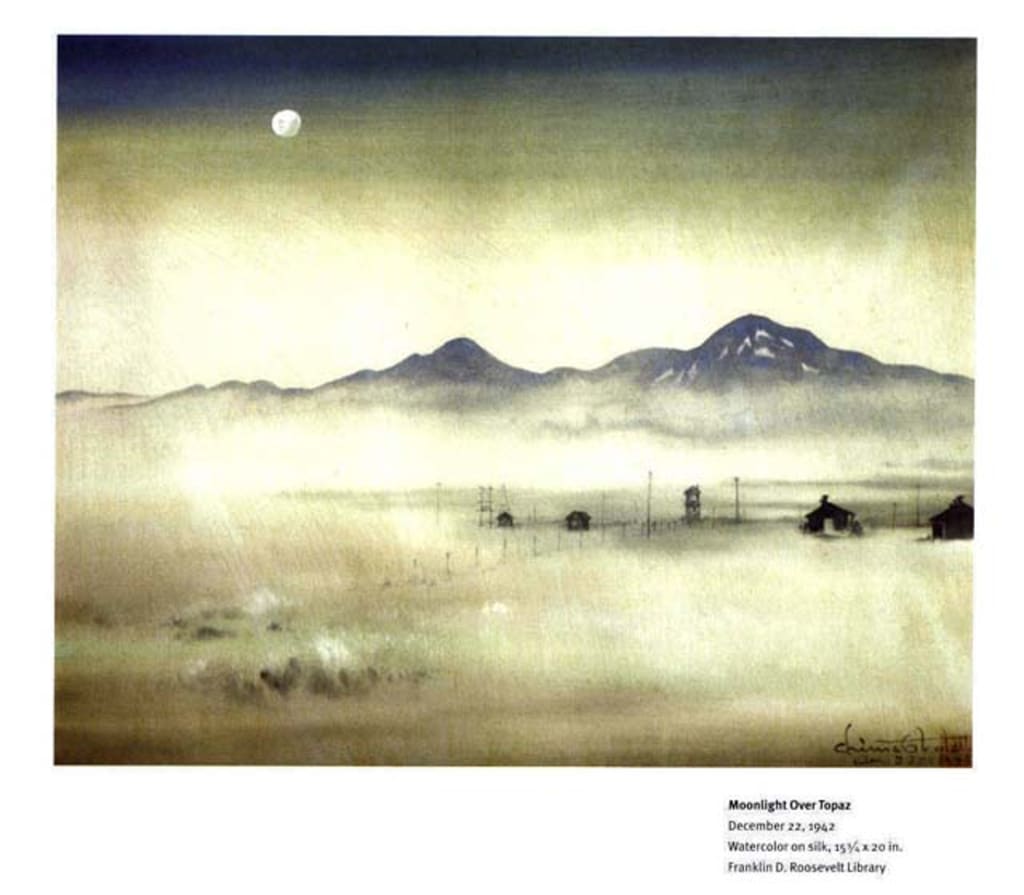

I wanted to show them the horizon of the desert, the silver light of the moon, the pure blue sky that answers our prayers over every dust storm. Did the loyalists truly think I was happy here? That I didn’t feel their indignities too, that I wasn’t human like them?

Another sigh, this one deeper and cleansing. I run my fingers carefully over my face, noting the rippling stitches and swollen divots, my new geography. I wonder how I look now. Most likely as ugly as the feelings that I nurse. In the art school, I just tried to give them something beautiful. This was my repayment.

I pick the pen up. Begin again, with Haruko’s ikebana arrangement first. There is splendor all around us, even in this barren hospital. I will find it.

6. May 18th, 1906. San Francisco.

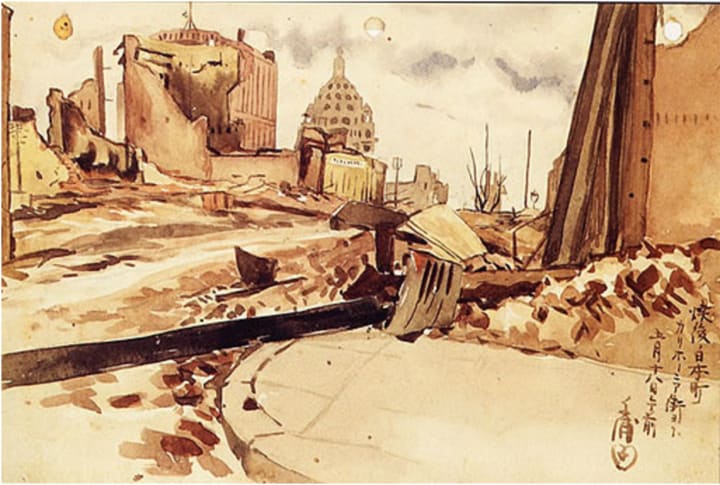

I hold my sketch against the burnt husk of Japantown, comparing the two ruins. I am happy with my choice to use the sepia ink, with just dots of black along the exposed beams to show fire-twisted nails. But something is missing. What?

I have the ash on the ground, piled like snowbanks. (How funny, I think. San Francisco’s first snow!) I have the telegram pole, toppled – and the bare, solitary lines of those still standing on the horizon. The half-crumbled walls like ripped leaves of paper. I shudder to remember my own home, not two blocks away from where I sit now. How the chimney fell into the living room as I watched from a doorway. Too scared to even scream as the earth rolled under my feet. I shake my head and return to the comfort of my sketch.

The dome of City Hall still looks impressive from this distance, the last sentry of the old skyline. But according to one of the officers from the Grand Marshal’s camp, it won’t stand for much longer. “It’s only the bones now,” he’d said at dinner as I served the men. “The fire just about ripped through it.” I’m especially proud of the dome’s fade into the smoggy sky.

Ah, yes. There is the missing link. The fire has long since burned itself put out, but its smoke still smothers the city. Thick clouds choke out the sun, casting everything in a muted light. Fitting for the view, I suppose. Not ideal for the clarity of my sketches. I soak my brush in water, then dip its tip into black ink. Very lightly, I dot at my skyline. A grayish haze emerges over my ruins.

“Time’s up, Obata,” one of the officers calls to me. “We have instructions take you back to the camp for the midday meal.” He approaches me and appraises my work in the fading light. “Wow. Almost looks pretty, on paper like that.”

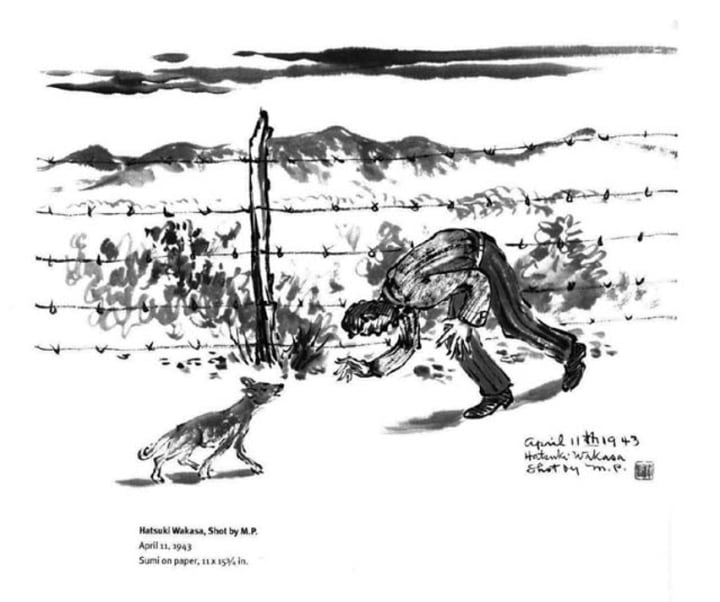

7. April 11, 1943. Topaz.

Director Ernst looks more ill than I feel, though I’m the one in the wheelchair. He sweats, pacing the length of the small administrative office a nurse wheeled me into. I am still too weak to stand on my own. “I’ve only got five minutes. A lot of fires to put out today, but I’ve got to make a choice about you now. It’ll take time to get things in motion, you see.”

“What are you talking about?” I ask. I know already. Rumors spread like wildfire even in the hospital, away from the open plan of the camp’s bathrooms (where I believe all of Topaz’s gossip is born).

“An old man tried to escape, walked too close to the fence, got himself shot. If he’d just listened – if he’d just stopped when asked…” he seems to be preparing himself for an inquest already, the implications of his words shifting with every clause. “You’ve got to leave. As soon as we can get the paperwork through. It’s a riot out there, and I don’t know yet what that means for you.”

“Is that necessary?” Even as I protest, I cannot help but feel an ashamed excitement. The outside world beckons to me. Art exhibits, trips to the wild, real toilet paper, the possibilities are endless. But still I feel an allegiance to the camp. To the art school I have built with Matsusaburo. To the moon’s silver outline on Topaz’s clime.

“Look, Obata. It’s for your safety. The folks up at the WRA didn’t tell me what your deal is – I don’t think I want to know, truly – but they’ve told me I’ve got to get you out. Do you have somewhere to go?”

I internalize this, glad now that we are meeting in the private office. To have this overheard would only serve to spur on the more damaging whispers. That I work for the FBI, that my job is to keep the internees placid and complacent. Not true. But in order to make the school so successful, I had to cooperate with WRA officials – how else could I get the tools for leatherworking? The iron for the sculpture class? Even the rulers and protractors for architectural drafting?

And when the loyalty oaths came, what was I supposed to do? Say “No,” I would not support this great, free country? I had chosen America long ago, had chosen its cliffs and lakes and forests as my home. I would gladly suffer anything just to see Yosemite once more. I made my allegiance to America out of love, love for its nature and love for its people. But would I die for them? Would I die by my own?

Director Ernst checks his watch. “I need to know now. If you stay, I can’t protect you.”

I make my choice. “I have a son in St. Louis. I can go to him. But my family comes too.”

Snores come from every side of the long room, but I sit awake. The words whispered by one of the nurses come back to me. “It was Hatsuki Wakasa, out on a walk with that stupid desert dog he loved so much. Dog chased a scorpion to the fence, he chased the dog. Guard yelled a warning. Didn’t know crazy old Wakasa was deaf. Or didn’t care. Shot him clean through the chest. Dog barking and howling the whole time.”

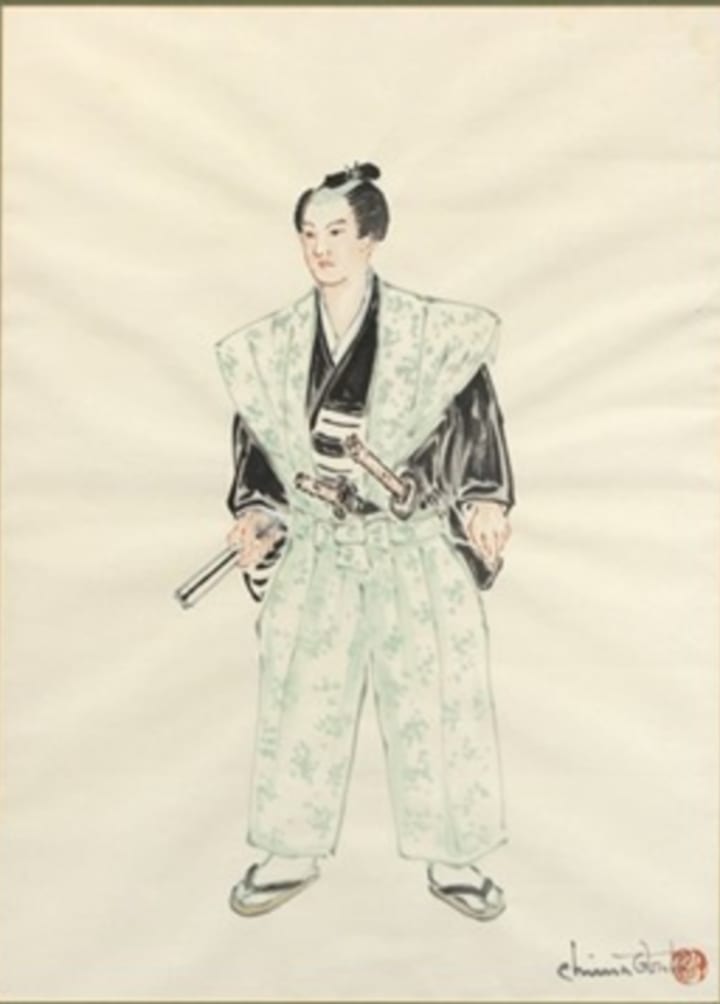

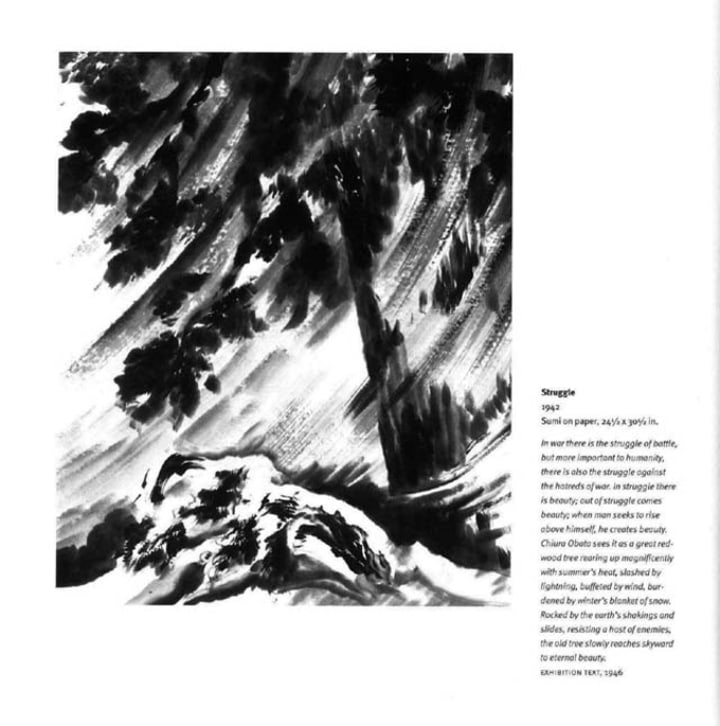

I find my set of brushes. I pour some water from Haruko’s flowers into the palette dish and grind at my ink stone. Enough of the moon’s weak, waxing light falls into my lap to make my cheap paper glow in the darkness. I paint Wakasa, tall and thin. Snapped over at the waist, dark pants and dirty shirt. Spider fingers spread in surprise. Mouth open, a pointless shout heard only by his panicked, fox-like dog. Between him and a furious scrawl of desert brush, I paint the lines of imprisonment: barbed wire, stretched thin. A sullen sky, dark and imprecise. Impassive mountains, fading at their edge.

I never fabricate. One of my teachers told me that I must always copy, never imitate. I have always held this as my credo.

But I don’t know what else to do now. This is the only tribute I can give.

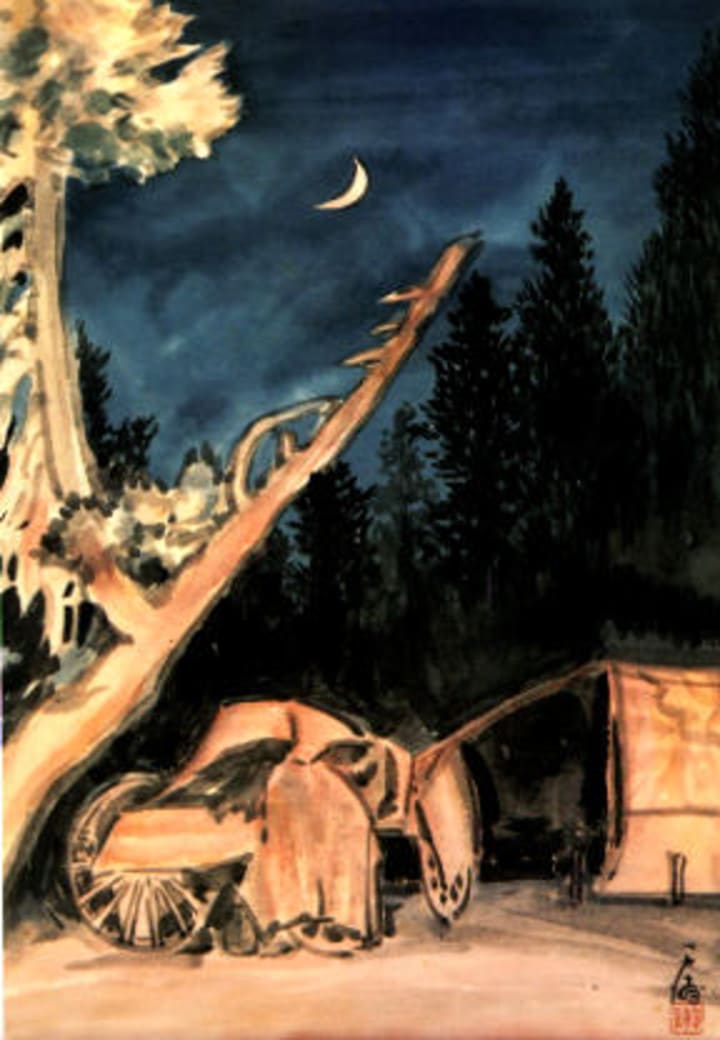

8. 1927. Yosemite.

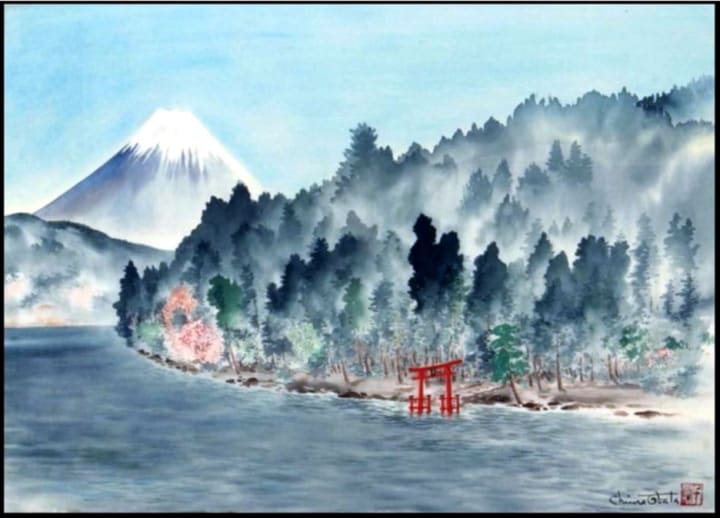

She wakes me past two with her light. The bright crescent curve of the moon, the cosmic daughter of Venus, shines her blessing in the river, on the woods, over me. With a blanket over my shoulders I sit by the embers of our campfire and watch Great Nature wake around me, emboldened by her light.

I had always thought nature was loud. Crickets, birds, wind. But up here it gets very cold. A coyote might howl in the distance, but under the moon’s arc the trees stand very quietly. Like the streams of Sendai, I sense in them a lesson to learn. Endless rhythm and harmony despite all borders – the lines between joy and despair, between strength and weakness, between nations.

This is a dream country. These are the days of the gods. I immerse myself, I listen to what nature has to tell me in its quietness. My feelings become as clear as full moonlight.

I reach for my brushes.

9. April 23, 1943. Topaz.

With a guard at my side, I walk from the hospital to the Main Gate – luckily, only a short distance. Other internees stop and stare to see me. The children wave, some of my students too. Others snarl. “Fucking informant,” a man shouts. The guard twists, trying to see who it was.

“Everyone back to their dwellings! Nothing to see here.”

But he is wrong. There is so much to see here. The sun is setting, but still I take in the spare rays of light gleefully. Above, the swelling moon rises and makes herself known. I admire the desert, as gray and unchanging as ever, with its disarranged hem of mountains.

Haruko meets me before the gate with my suitcase and a pile of papers wrapped in tattered cloth. My sketches, the precious record of my time here. She strokes my damaged face. “It really will scar,” she clucks.

“Not before I see you next, Mama.” A long pause. We do not know yet if that is true, can only hope. But in the warm light of the sun, with the wind whipping at her skirts and caressing us lightly with the desert’s powder, nothing seems impossible.

A car pulls up, the taxi that will start my long journey from Topaz. As I hurry my goodbyes to Haruko, the guard opens the gate and ushers me forward. I hesitate at the boundary to the outside world and admire the camp’s militaristic sprawl.

I feel like running from the guard and bounding into the art school, just behind the hospital in Block Seven. “Look! To the East, the Rockies! So grand, with snow on top. To the Northwest, our Topaz with its color beyond description – paint it instead!” I will miss the Issei, who came into my classroom with nothing – possessionless, homeless, stateless – and left as artists. I will miss the children, who clamored at the doorway even during the fiercest dust storms. I will even miss the administrative work: the desperate letters to officials for funds, the pleas to my citizen friends to send what materials they could, the shuffling of thousands into the capable hands of our few teachers. Without much surprise, I realize that I will miss the whole of this godawful, desolate camp.

How can I explain it? Here, watercolors freeze on paper. Dust storms moan like heartsick men, begging to be let in through our gum paper screens. The sky hangs heavy with us at the end of our depressive days. And every morning, we rediscover the reflected dawn bright against the snow-covered Mt. Topaz. We will learn from Great Nature. Like her mountains, we will endure. Like her sun and her moon, both visible against the pale sky, we will emit our own light. The blank canvas of our dustbowl is scrubbed of vegetation and ready for our grace.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (1)

Beautiful story and introduction to an artist I hadn’t heard of. All I could think while reading this was, no good deed goes unpunished. At least he got as much as he could from the experience, even if his presence wasn’t appreciated by everyone.