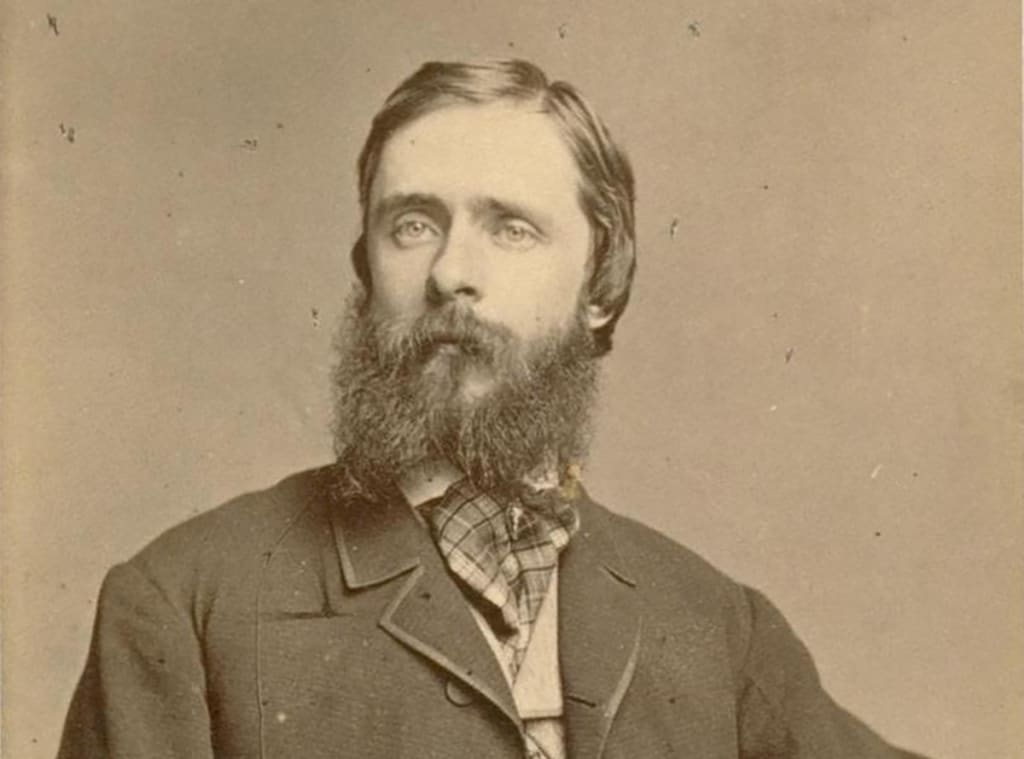

Who Was Fitz Hugh Ludlow?

As the first authentic cannabis culture literary celebrity, Fitz Hugh Ludlow wrote from experience.

I was never particularly interested in 19th-century literature. There were so many things our English teachers didn't tell us, especially when it came to the counterculture underground books of the Victorian era. They never mentioned that Charles Dickens, for instance, wrote his last novel stoned. Several key scenes in The Mystery of Edwin Drood were set in an opium den and hash lounge. Or they'd ramble on and on about John Greenleaf Whittier's "Snowbound," never mentioning his interesting little poem "The Haschich." Sometimes we'd get maybe an hour of English class devoted to an excerpt from Thomas De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1822), because it was the first great English drug tale and influenced all the Romantic writers. But we never heard about, America's first great drug writer, Fitz Hugh Ludlow.

It was different during Ludlow's lifetime, when he was one of the most famous writers in America. Born in 1836, he grew up in Poughkeepsie, New York, where from a very early age his favorite hang-out was the neighborhood apothecary's shop. After reading De Guincey's Confessions, he started experimenting with every drug he could get his hands on—chloroform, ether, opium, stimulants, the whole range of strange anesthetics and potent medicines on the apothecary's shelf. At the grave old age of sixteen, he wrote, "he sat down like a pharmaceutical Alexander, with no more drug worlds to conquer."

One bright morning in the early 1850s, however, the drug store owner showed him a shelf of new bottles which had arrived from Tilden and Company, one of the biggest manufacturers of plant drug extracts. "Conium, taraxacum, rhubarb—all what is this? Cannabis Indica?" Ludlow asked.

"That," said the friendly druggist, "is a preparation of the East Indian hemp, a powerful agent in cases of lock-jaw." Fitz Hugh Ludlow immediately uncorked the bottle and started to take some, "Hold on," said the apothecary: "Do you want to kill yourself? That stuff is deadly poison."

After reading several dispensatory articles about cannabis Indica, Ludlow learned that it was the hasheesh and cannabis which travelers had written about, used by millions of people around the world every day. Purchasing the bottle, he first tried 10 grains of the extract. Nothing happened. A few days later, 15 grains, and again no effect. Gradually increasing the dose, Ludlow had to take 30 grains (almost 2 grams) of the extract before he got off. He spaced into an "infinite journey" of intense hallucinations and his career as America's first great cannabis connoisseur was begun.

When he was a senior at Union College in Schenectady, NY, Ludlow wrote an essay on "The Apocalypse of Hasheesh" for Putnam's Magazine, one of the fast-growing literary monthlies (others were Harper's and The Atlantic Monthly) which were revolutionizing American journalism by bringing articles on contemporary affairs quickly via the railroad to an eager mass market. A year later (1857) Ludlow expanded the essay into the first comprehensive discussion of cannabis use in world literature, and the first full-length American drug classic, The Hasheesh Eater. Published by one of the most prestigious presses, Harper and Brothers, the book was avidly read all over the continent: my own copy of the original edition came from the Placerville gold camps of northern California in 1860.

The book established Fitz Hugh Ludlow, then twenty-one years old, as one of the most promising writers in America. He went to New York and was quickly accepted among the writers of the Gotham Literary Circle, several of whom—like Thomas Bailey Aldrich, who later became editor of The Atlantic Monthly—were inspired to try the drug. Significantly, Ludlow's book and personal presence amidst the major authors and journalists of the time had the effect of arousing nationwide interest in "hasheesh" both medically and recreationally. People were hungry for any interesting diversion from the deepening controversy over slavery which soon led to the Civil War, and doctors everywhere were soon prescribing cannabis extracts and tinctures for migraine headaches, nervous tension, and even tetanus, cholera, and tuberculosis. Opium use became so widespread during the Civil War that addiction was called "the soldier's disease," and when opium and morphine supplies ran out, almost any substitute like cannabis was used to kill pain.

Ludlow himself suffered from tuberculosis and went West for his health in 1864. His account of the journey, The Heart of the Continent, correctly predicted the exact route of the transcontinental railroad. He toured Yosemite with a famous painter, Albert Bierstadt, and when he arrived in San Francisco he was ionized as one of the greatest authors alive. There he met the struggling, unknown "Golden Era" group of writers—Mark Twain, Joaquin Miller, Bret Hart, and others. At a time when Mark Twain's reputation was local and floundering, the famous Ludlow wrote a "high encomium" on the young author, which Twain later reciprocated.

One question the history books have not been able to answer is whether Ludlow turned Twain on to hashish. Interestingly, the next story Twain wrote was "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," a wild tale about two guys who fix it so their entry wins the frog-jumping contest in a gold camp by filling the local frog champion's stomach with buckshot. It's just the sort of thing two high-spirited young pot heads might do to the rough-and-tumble miners, but I suppose we'll never know for sure.

Ludlow returned East and devoted the rest of his life to writing stories for the leading journals of his day, including a powerful treatise on opium addiction, "What Shall They Do To Be Saved," in which he recommended cannabis is one of several possible agents to cure addiction. Still suffering from ill health, Ludlow himself became addicted to opium. In a last desperate attempt to cure his tuberculosis, he went to Switzerland in 1870 to consult the best European doctors, but it was too late. He died in Geneva on September 12, 1870, one day after his 34th birthday.

The most important thing Ludlow left us, of course, was The Hasheesh Eater. The book imprinted America's most important Transcendental and Gotham writers with graceful, extravagant, and sometimes horrifying visions of hashish. The effect on American culture was more profound than contemporary historians usually care to admit. A great number of physicians, pharmacologists, and literati experimented with the drug, and they in turn inspired the first generation of widespread cannabis use in America. By 1876, when America was celebrating its first centennial, the Turkish exhibit at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition featured well-dressed American gentlemen smoking hookahs and 8' long Turkish hash pipes. The same year—only twenty years after Ludlow's essay, the New York police began describing the "Hasheesh Hells on Fifth Avenue," where fashionable young women would go to turn on. By 1883, luxurious private clubs devoted to hashish smoking existed in all the major cities from New York to San Francisco, Boston to Chicago, Philadelphia to New Orleans. The so-called "drug experts" who insist that cannabis use in America began in the 1920s should do their homework a little more carefully.

Fitz Hugh Ludlow was the first writer to describe the long-term effects of chronic cannabis use, and it is because of this that he illuminates our own era. The "hasheesh" he took was, in fact, Tilden's cannabis Indica, a thick resinous extract rather similar to the hash oils in current vape pen cartridges. The experiences he described under high doses of this tincture are nothing less than psychedelic trips into new dimensions of inner space. His work thus assumes more than mere historical relevance to present-day hallucinogenic drug use, of marijuana, hash oil, or acid.

About the Creator

Frank White

New Yorker in his forties. His counsel is sought by many, offered to few. Traveled the world in search of answers, but found more questions.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.