Please Steal My Book

Or: Why I Write For Free While Inviting Others to Profit

Within the tilted world of would-be authors, there are a few people who don't have a good grasp on their circumstances. There are, of course, those who are convinced that literally everyone wants to steal their book, but there is another group that is much more jaded while remaining no more realistic in their outlook.

There are certain conversations draw this particular group to the surface. Go to any writer's forum and start talking about your latest book giveaway, maybe mention that you're thinking of serializing your next book on your blog where anyone can read it. As sure as gravity draws us all back to the surface, so will they appear with a snort and an eyeroll and a snarky "Oh, you'll never make money that way, stupid." They'll then follow this up by bragging about the $17 they made on KDP last year, perhaps followed with a abbreviated tirade on how they could have made twice that if people like you weren't destroying the industry.

It's one of the less charming groups you'll encounter on your path of failure. At least the kids scared to death that you want to steal their Dragonlance fanfiction have the excuse of naivete, but the latter are driven by pomposity more than ignorance. They feel that they should be rich, and it must be someone's fault that they're not - and you, filthy internet novelist that you've revealed yourself to be, are as good a target as any.

But what's so wrong about wanting to be paid for what you do? In a media environment defined by "payment in exposure," where writers have been devalued even as more demand is put on our skills, shouldn't we stand firm on this point? Shouldn't we stand against all those people, both inside and outside of the industry, who insist that it's egotism to want even a token payment?

There are a lot of people who will tell you that you should never work for free...and that includes me! I've certainly been paid for my writing - sometimes a lot, occasionally far more than it's worth, but more frequently a good faith pittance. I will take money if you offer it to me; I'm always going to prioritize paying markets over non-paying ones, exposure be damned.

And yet, I also give away just about everything I do for free. Those paid-for stories land on my own site or someone's else just as soon as the rights revert back to me. All my novels end up there as well - don't even look for them on Kindle Unlimited, the new home for people who want to sell their work but aren't confident that they can get a customer to part with $0.99.

I'm even so casual about all of this that I won't kick if you try to profit off this free material.

So what's the deal?

The deal is that the world is more complicated than the simple rules we try to live by, and that world is complicated enough for more than one kind of writer. You have, on one hand, journalists - people who make a living at this sort of thing, or at least aspire to. These individuals should never, under any circumstances, work for exposure. They should get paid, and they should get paid more than I do for my work.

On the other hand, you have fiction writers, and this is the group from which most of those charmless people are drawn. For most of us, making a living with fiction is less an aspiration than a pipe dream, one that's way off in the distance. Closing that distance requires a lot of exposure, and that money you're making - a trim fraction of what a journalist would expect to pull in - is important symbolically more than practically. With luck, you'll pay the bills one day, but right now what you need is to get published in the kinds of markets that are important enough that they will pay you. That's how you win the race.

Of course, there's nothing wrong with refusing to touch pen to paper without cash money being involved, but that's ultimately a strategic choice. I have my own strategy, and I justify it on two grounds: One pragmatic, one principled.

Seriously, You Can Steal My Books

Most of what I do comes with this banner attached:

That's a Creative Commons license. It means that I am giving you permission to use the associated work, subject to just a few requirements. To wit:

- You must include my full name.

- You must link back to my website.

- If you change anything, the product must also be Creative Commons with an SA (Share alike) license.

And that's it. Do those three things, and you're good to go. Oh, and go ahead and assume that everything I have on Vocal is under that license, even if it isn't explicitly tagged as such - this article certainly is, and you are thus free to use and reuse it as you wish.

Lots of writers use Creative Commons licenses, but mine is a little different in what it lacks: A non-commercial (NC) restriction. That's exactly what it sounds like - NC licenses don't allow reuse for monetary gain. Mine does.

Again, I hear the chorus sound: Are you insane? No, friend, this is all part of that strategy I mentioned. I'm not going to judge the many other people who employ NC licenses, who have some valid concerns (albeit concerns that aren't convincing to me, obviously). This is as much marketing as it is principle.

The Strictly Business Reason I Do This

A lot of this comes from the world of music.

Aspiring musicians are frequently given advice to the effect that they should think of themselves as selling a service rather than a product. This shift is something that musicians have been facing for a while. Most will put the big turning point around twenty years ago with the rise of file sharing, but I'll argue that the predatory nature of the industry has made music-as-service a reality for much longer than that. Lots of major albums made little to no money for the artists, who had to make their money through ancillary streams - concerts, merchandise, and licensing.

To my eyes, writers are reaching the same place where musicians were two decades ago - not because of piracy, but because of increased competition and natural shifts in the market. For a certain type of practical, money-oriented author, it's still realistic to make money selling books. It's even viable for a particular breed of genre writer capable of turning out five readable manuscripts a year. But for the rest of us, living as we do in a world where a "successful" novel may only make a few grand per year, the money isn't in the book. It's in the reputation that comes with the book.

Being an "independent" writer ain't cheap these days. Ten-odd years ago - back when I still thought I could sell a book as a product - this was both easier and cheaper. Say I wanted some reviews - all I'd need to do was schedule a short free period, send out some emails, add my name to some free referral services, and it was done. These days, you'd better have a budget, because there's plenty you'll need to buy - vanity articles linking to your book, a useless but nice-looking press release, promotion for your giveaway on premium lists (you'd be surprised what it costs to spread the word about a free book), a book trailer no one will ever watch, copies to give away to people you hope will give you good reviews, maybe even a few bribes to some "influencer" accounts.

This is what it takes to stand out when there are hundreds of competing titles coming out each day. It might take thousands of dollars just to get to the table and roll the dice once. That strikes me as a bad deal, so I found an alternative:

I pay you on contingency: You do the promotion, you keep the money.

Go ahead, steal everything I've ever done. I doubt you'll make much money on it, but maybe you will. In that case, good for you? And more importantly, good for me! In all likelihood, whatever benefit I've accrued to my brand is, in the long run, worth more than you made - and the money you made was money I wasn't going to make anyway, so it's all upside for me.

Here, listen to me ask - nay, demand - that you steal one of my books and try to profit from it:

And how might you make that money? Let me give you an example (and a subtle hint): Podcasts. There are a lot of fiction podcasts these days, some of which are very popular. Many writers, if they find that these podcasts have rendered their work in audio, will pitch a fit. I won't, though. You guys are the best, and whatever money you can squeeze out of a short story that's been rejected 20 times already is more than I would have made - and in exchange, I get lots and lots of new readers.

That's not a bad deal, huh?

Oh, but would that it worked this smoothly. Podcasts aside, there isn't as much of a market for Creative Commons writing as there is for Creative Commons pictures, video or music - all of which can be broadly reused for other projects. People who think of themselves as creatives always want to do the writing themselves, and only want help with the other parts. Leveraging the greed of others likely won't get me as far as I'd like.

Which leads me to the other reason I do this - the heavier, more principled one.

The Deep, Emotional Reason I Do This

I write in a few different genres, but what you'll be most familiar with from what I've posted here is my speculative writing - concept-driven science fiction. This material has its roots in variety of sources, mostly things I'd read or seen that seemed like they called for exploration.

In short, this work isn't personal. Some of the other pieces, however, are.

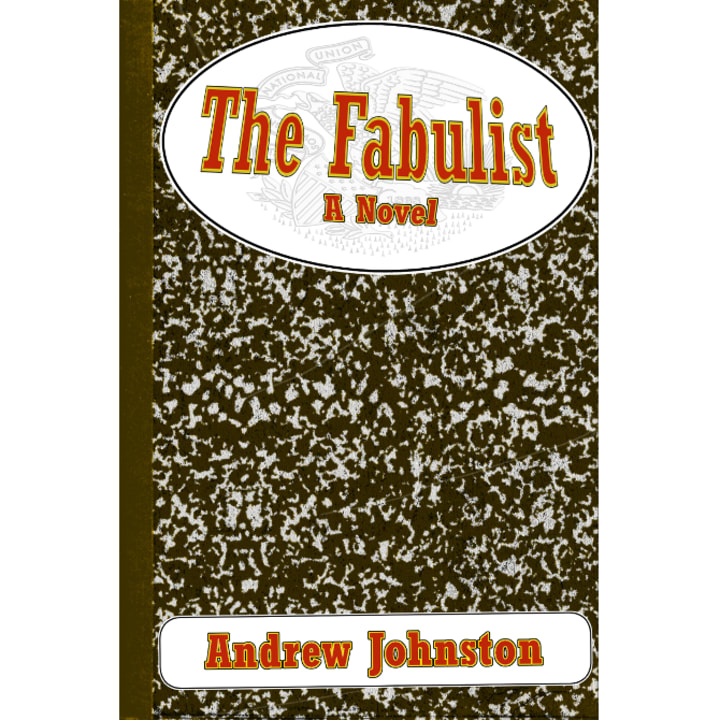

About two years ago, I wrote and posted an essay on my writing blog titled "Why I Can't Let The Fabulist Die." This concerned one of my novels, the best in my opinion and one of the few that seemed like it had a real shot at success. This came after the manuscript had been rejected by over 200 agents, after I'd tried and failed to sell it myself - resorting to cheap, ineffective stunts, one of which I detailed here - after I'd rewritten it from the ground up, had it rejected by dozens more agents and publishers, and was down to giving it away for free to scraper bots.

The question I meant to answer was "Why the hell am I trying so hard to promote something that's been a disappointment for six years?" The answer was simple: This is a story born from pain. It doesn't deserve to be ignored.

So I made a deal with the world: I shall give you The Fabulist for free - and other works that I care deeply about, other works that were born of my suffering. If you think this is worth money, then I'll take it from you, every cent you care to part with. If you don't think it's worth money but you're willing to spread the word, I'll take that, too. And if it's worth nothing more than a read-through, and you get something out of it? Then good for me.

My work is worth exactly what you think it's worth. I trust that someone out there will see real value in it, and will pay to see more like it. I have that much confidence that, in the long run, this will lead somewhere good. I have the much confidence because I believe in what I do, and I've never stopped trying to improve.

And if I'm wrong? Well, I'm only out $17.

About the Creator

Andrew Johnston

Educator, writer and documentarian based out of central China. Catch the full story at www.findthefabulist.com.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.