The 'Violet Protest' Was An Art Campaign We Needed – Even If Its Audience Hasn't Yet Responded

Artist Ann Morton Protests Divisiveness and Promotes Eight Core Values to Heal US

Thanatophobia: fear of death or dying. Athazagoraphobia: fear of being forgotten or forgetting something. Disposophobia: fear of losing something. Three terms I recently learned. Three terms that have likely crept up behind each of us over the past two years. On some level, most have had to reckon with thanatophobia. Many have felt afraid of forgetting to wash our hands, or not touching our face, or socially distancing. Most of all, perhaps, the fear of losing something precious (and perhaps it's not even a thing)—community, connection, sovereign democratic liberty Herself—has been staring down every American for years now. Each unfolding news cycle brings us ever closer to that final back-breaking hay straw. “This…” we’ve each likely said aloud at some point since January 2020 (whether hyperbolically or in earnest), “...this is what’s going to finally upend the country forever.” With different experiences of the pandemic, the rallies for social justice, and the election fallout—even different truths about them—each of us has been compelled to reckon with a fear of losing America (or integral parts of Her). Sadly, this fear might be one of the strongest unifying factors in our present condition as a country.

Consider these words: “It was hard to be moderate in immoderate times.” Also, “Sectional conspiracy theories were eroding cross-sectional trust inside and outside of Congress, destroying any hope of a middle ground.” While these chilling lines from Joanne B. Freeman’s 2018 book, The Field of Blood, might accurately describe current American political culture, the Yale Professor of History and American Studies was actually writing about centuries-old, pre-Civil War animosities. Throughout her book, subtitled Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, Freeman deftly relates the mid-19th-century fracturing of America to our modern cultural and political infighting. We should all be organizing community reading groups to discuss it. Her book is a warning that things could become again as they once were by bloody schism. The author acknowledges how Trumpism and the Republican assault on truth, representative democracy, and the American narrative parallel the pro-slavery political playbook of achieving victory through taunting opponents, bullying, and open threats of violence. A further Freemanism for your consideration: “As a representative institution, the U.S. Congress embodies the temper of its time. When the nation is polarized and civic commonality dwindles, Congress reflects that image back to the American people.” Even further, still: “Democracy is an ongoing conversation between the governed and their governors; it should come as no surprise that dramatic changes in the modes of conversation cause dramatic changes in democracies themselves.”

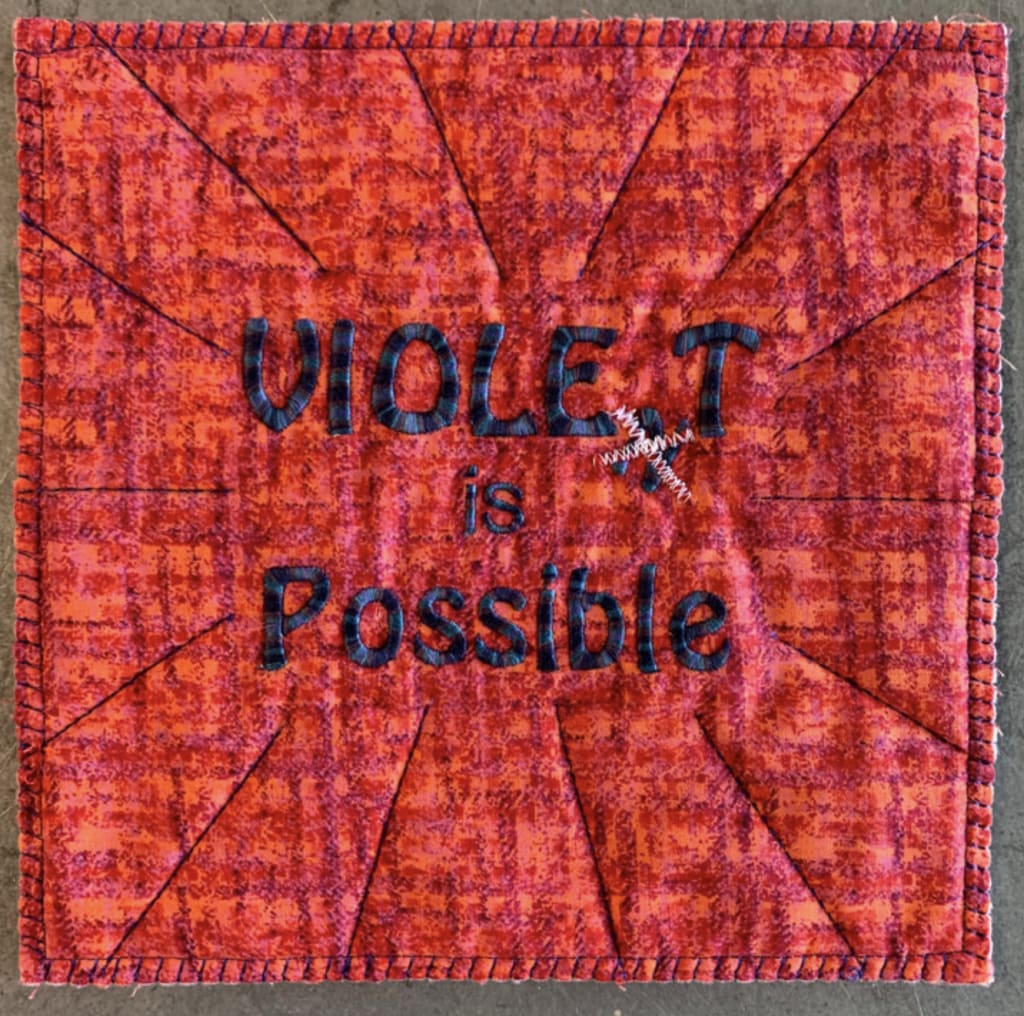

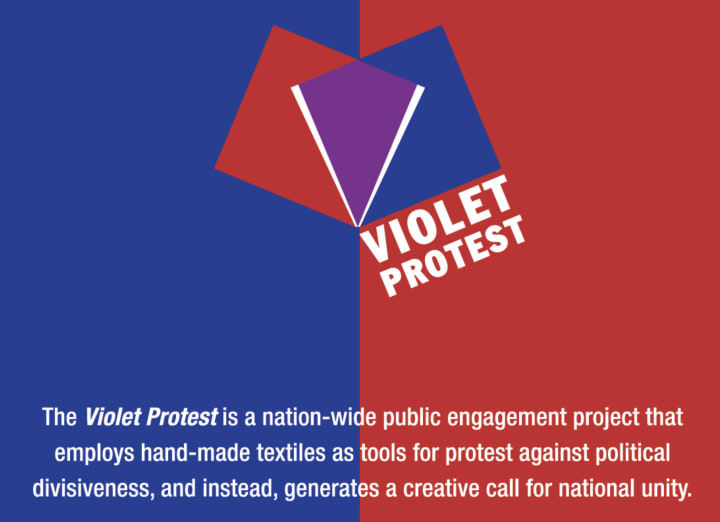

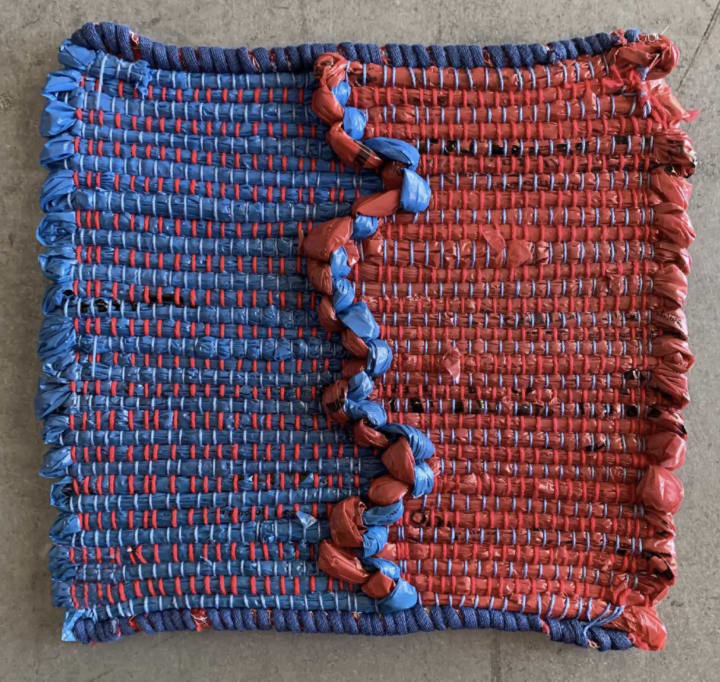

I recalled Freeman’s book in January while viewing a presentation—through a monthly Zoom meeting of the Southern California Handweavers’ Guild’s Tapestry Study Group—by Arizona-based fiber artist Ann Morton about her recent public art intervention, the Violet Protest. As per its website, “The Violet Protest is a public effort to send bundles of hand-made textile squares to each and every member of Congress in support of these core American values: Respect for the other; Citizenship; Compromise; Country over party and corporate influence; Courage; Candor; Compassion; Creativity.” Each square measures eight-by-eight inches and is composed, more or less, of equal parts blue and red material, colors of which when blended become violet ("...one letter away from violent," as Ann pointed out during the presentation). Violet Protesters, therefore, became maker-advocates of open bipartisan dialog and American unity.

Auspiciously, Morton launched Violet Protest in January 2020 and accepted square submissions until September 2021 from all fifty states, D.C., Puerto Rico, all U.S. territories, and Canada. In a real sense, squares made by Violet Protesters represent a time capsule of recent national turmoil, an archival American history of the pandemic. Each square is a historical artifact reflecting a unique perspective on American values; each shows a part from the larger timeline of recent transformative events. All told, more than two thousand maker-advocates in the Violet Protest produced around 13,500 squares that represent roughly 60,750 hours of handwork (clocked at around 4.5 hours per square).

During much of 2021—from Spring to Autumn—the efforts of Violet Protesters were displayed in nearly 10,000 square feet of the Phoenix Art Museum, with the exhibit expanding weekly to accommodate new arrivals. Each textile square represents hours of optimistic mindfulness by someone somewhere in North America who believes we are still united based upon shared values, that we can craft hope and inspiration together. The outpouring displayed in the installation is staggering. Examining one square at a time feels like looking at different interpretations of the same emotion. Each conveys love like hearing a single meditation among a throng. Synesthesiatically, each sounds to the eyes like a specific proud cry from out of a migrating flock. Looking at one is like appreciating a unique cleansing drop of rain in a summer afternoon downpour, then another.

Following their exhibition in Phoenix, squares were grouped into stacks of about 25, placed into cardboard boxes (along with the names and locations of their makers and any letters to Congresspersons they’d included), and mailed off to all 540 members of the 117th Congress at the end of November 2021. After processing an artistic outpouring from across North America, Ann Morton and the Violet Protest Steering Committee waited for a response from Congress. From anyone in Congress. And they continued to wait. And wait. And as of early February (at the time this article is being written), the Violet Protest has yet to receive any response at all from anyone in Congress. Democrat or Republican.

Sometime after November 2021, more than 13,000 intricately beautiful and endlessly fascinating textile squares—each made with compassion and more than a smattering of engaged patriotic craftsmanship—made their way inside the Capitol building via the USPS, and there they (theoretically) remain and sit today. Unanswered. A vast, mind-boggling display of love for the promise of our democracy (that insists upon stirring deep emotional feelings in any viewer) has seemingly all but gone unseen, unheard, and unattended to by those for whom the effort was directed. Violet Protesters emphatically invited those in power to embrace a crucial set of values, yet their breathtaking call has gone unreturned for months. The recipients of this new national treasure remain silent and unstirred, at least for now.

In the face of divisive political rhetoric, cultural attacks on academics and science, exploitative media, disaster capitalism, global systemic failings, cancel culture, and inflamed conspiratorial neo-fascist nationalism, Violet Protest defiantly and creatively implored its audience to reconsider their own efforts, actions, and creations toward national reconciliation. One maker at a time, one textile square after another—stitched, knitted, woven, quilted, crocheted, embroidered, dyed, beaded, zippered, felted, and beyond—each square crafted with dissent against division, bristling with fortitude for our future. I buzzed as I scribbled notes during Ann Morton’s presentation. Questions formulated. I wanted to talk with everyone involved. I suddenly wondered, who really is the audience? Is Violet Protest ultimately intended for Congress (as its mission states), or is it a feel-good visual for the internet; the makers; perhaps a reforming cynic like myself; exhibition visitors at the Phoenix Art Museum; or was it all actually for the artist, Ann Morton? To whom does this effort speak, and what does it articulate? My political mind folded over on itself.

I arranged to speak with Ann Morton on a morning in early February. I wanted to discuss possibly organizing a series of roundtables with some of the maker-advocates—the VPs (Violet Protesters) as they’re called on the website—or implementing an exit survey for the VPs as a kind of debriefing of their experience. I was eager to talk with the artist, whose website describes how she explores themes of “social divides we’ve come to accept as normal cultural paradigms… homogenization… [and recognizing the] insignificant…” via public art interventions.

After discussing my intentions to write about the Violet Protest, I learned more about how she organized the project and a bit of specifics about participant outreach. Ann Morton engaged existing fiber arts networks, associations, and learning spaces to promote the project. Turns out that, in the 21st century, this Union of States can still be rallied through fiber arts; and fabric artisans are, indeed, a patriotic bunch. Still, my contrarian brain eventually steered the conversation toward the thing I’d been avoiding. “I have to ask,” I blurted after a time. “What was the political makeup of the VPs? Was this really a project for Red and Blue dialogue, or is it really just Red that needs to change?” Ann laughed, and I think I understand why. She stayed cool, though, and said she believes the political affiliations of participants to be around 75-25%, Democrat to Republican, while those numbers differed state by state.

“This was about crafting dissent,” she explained. “Historically, it tends to be that two factors define those who participate more often in craft-based protests: they’re typically liberal, and usually female.” She pointed out that a short documentary film is being made about the Violet Protest, and that the videographer is conservative. “It's very important to me that we have that perspective and viewpoint around during the project,” she said. Lamenting, Ann also described how it’s possible that some of the early VPs who leaned conservative may have lost interest or faith in the project as it went on. “This all started as an activist effort to bring blue and red together to promote dialog and unity, and along the way, there was a little bit of Republican pushback—to things that were said in the newsletter or on our Instagram page [about events that were happening in the country].”

Looking over the Violet Protest Instagram account, it’s easy to see what Ann might be talking about. More recent posts often show a textile square “Destination of the Week” and include a caption that often relates the work to current events or news items (captions for these “Destination” posts have grown more pointed and forthright when compared with earlier “Squares of the Week” which were posted while the project was underway and whose captions were more bipartisan). A recent post shows one of 5 handmade squares by Helen Geglio of South Bend, IN, which was shipped to Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming. This square is made of perhaps a dozen swatches of blue and red fabric stitched together or mended. The caption states, “Helen’s square speaks to the mending our country… needs… but to do so, each side must be held steady and in place to receive the mending stitches. No matter the politics, Rep. Cheney seems to be holding firm—looking beyond the rips and tears to the repair that is possible.” Considering the RNC censured Rep. Cheney, along with Rep. Kinzinger, because of her candor and courage in putting country over party and corporate influence, the caption is a brave dissent against divisiveness that honors citizenship and compromise, yet it likely sparked conservative ire.

Another post from just a few weeks earlier in December shows a square made by Darlene Khosrowpour of Pflugerville, TX, which depicts red and blue silhouettes on a white background with a large dialogue bubble between them that’s filled by red-blue shapes (a triangle, a spiral, a diamond, and a stylized heart). The square is dedicated to Senator Ted Cruz of TX. Its downright partisan caption reads, “There’s lots of talk in Congress—but really how much listening is there? It’s easy to grandstand, but harder to hear what your colleagues are saying.” It turns out that focusing on values and really meaning it isn’t a steady, straight line. It doesn’t mean ignoring uncomfortable conversations, but rather leaning into them and, occasionally, shining a light on lapses in those values. That Conservatives who joined a movement promoting honest dialog might grow disillusioned when that honest dialog needs to reckon with the words or actions of GOP politicians is, well, lamentable. The Violet Protest is also only a call to action. A bard can only sound the horn, after all; the listener must hear the cry and respond accordingly as best they can.

“This was always about motivating people to make. There’s a visual spectacle, but it also has a social purpose,” Ann said. “It helped people feel like they were doing something worthwhile, something to occupy their time, but also something to believe in – a personal belief.” That belief, likely, was unique to each Violet Protester. The project promoted eight core values with a call for bipartisanship and produced so many different interpretations along the way, its efforts ultimately landing somewhere in a mail pile in one of the hundreds of Congressional offices in the Capitol. Ann remains, and astoundingly so, optimistic about the lack of response from Congress. “Whether we hear back from any of them or not,” she said, “I have to believe that [the mission to affect change] will happen. And we may never know [if Members of Congress saw the squares].” Ann described how the hopeful energy that makers put into each square made it into the Capitol, to their intended Congressperson. “The energy is there,” she says, reassuringly. “And my understanding is that all of the Congressional office staff, they all talk to each other. So, you know, they might all be asking each other, ‘Did you get that big box full of little squares?’ and things like that. Those conversations might already be happening.”

Part of me wants to call Congressional offices every day, or fly out to D.C. with a stack of question cards and a notebook and knock on doors in the building, but that may not matter. Not in the slightest. Instead, perhaps I need to recall Joanne B. Freeman, yet again, and how Congress “embodies the temper of its time.” Perhaps it’s really up to me to have those red and blue conversations. To push those with whom I disagree to acknowledge a need to lower the tempo and actually dialog. If there is a way to create unity in this country, it may mean we’ll need a lot more of these kinds of projects. “The energy in the [exhibit] room [at Phoenix Art Museum] was palpable,” Ann Morton said when asked what it was like to hold that space for nearly a year. “I’ve worried,” she continued, “about splitting up all of the squares from the display—about getting them into separate boxes and mailing them out to Congress—I’ve worried about twenty-five squares holding the energy of all of them. It was amazing to see them all together.”

Before we finished our conversation, Ann Morton agreed to share a set of quotes the Violet Protest committee pulled from letters and notes the VPs had included with their submission(s). Sometimes these writings were for the artist, Ann Morton, but more often they were intended to reach, along with their textile square, a sitting member of Congress. Reading through these collected words from the makers themselves gives a sense of the kind of palpable energy in the exhibition hall that Ann had described; a little of what it must have been like to stand in that room in Phoenix. They talk about how much this project helped them make it through the year. They say how America is unfinished; imperfect; a work in progress; a developing story; a multifaceted display of patterns, setbacks, and intricate beauties. So many of them stitch together inspiring textile-based metaphors or similes or imagery about our country and its people. The makers talk about how this project needs to be seen and heard and acted upon. More than anything, the VPs repeatedly called on the powerful, the political agents in Congress, to wake up and acknowledge the project’s core values.

Ann Morton is almost nowhere to be seen in this entire project. She is behind everything and all the while standing at the forefront with a bright smile. How could she not be elated after sparking so much hope and creativity and action? In the end, the intentions of Ann's Violet Protest were to engage the public in bipartisan activism coupled with an accumulated meditative focus on the eight core values through tens of thousands of hours of production. The squares, like their makers, represent a range of beliefs and political allegiances; they might be evidence of the kind of change we need; an act of outreach as the product of rebellion.

Like the creators of The Pussyhat Project (to highlight Women’s Rights), or 'The Local Love Brigade' postcard writing campaigns (to support those who have been targets of hate), Ann Morton is a community hero for concocting a giant excuse for people all over the country to begin to think differently about political discourse. She gave Americans a reason to be makers, to share knowledge and techniques, to reexamine their own roles in healing and building a better future, to consider one another as equals rather than as opponents or enemies, to inspire their children, family, or even themselves. The Violet Protest wove creativity through towns and communities across all fifty states and beyond at a time when we had such a dearth of examples of unity. For myself, this project reminds me to go deeper into my values and actions, to reach out rather than recoil. This project helped regular people practice kindness and inclusivity for a combined total of more than 60,000 hours; it inspires these same practices in those of us who only came across the project after it concluded. Clearly, there’s a demand for Violet Protest; certainly, we need more opportunities like it to combine our talents and co-create. This campaign gave Americans a chance to craft a better story about unity; a narrative that combined the best of what we are and want to become; a plot we can develop in unison based around uplifting everyone through eight unflinchingly American values. Respect for the other. Citizenship. Compromise. Country over party and corporate influence. Courage. Candor. Compassion. Creativity.

About the Creator

Philip Canterbury

Storyteller and published historian crafting fiction and nonfiction.

2022 Vocal+ Fiction Awards Finalist [Chaos Along the Arroyo].

Top Story - October 2023 [All the Colorful Wildflowers].

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.