Above: The Nineteenth-Century painter Daniel Maclise imagines William Caxton around 1476, demonstrating the first English printing-press to King Edward the Fourth and his royal family. The girl directly in front of the Queen is Elizabeth of York, whose marriage to King Henry the Seventh would end the Wars of the Roses and usher in a long-overdue era of peace. A more tragic destiny awaits the King’s two sons, situated at the very centre of the tableau, who today are remembered as The Princes in The Tower.

1) Introduction to the Period

The Middle English period of British literature begins with the Norman Conquest of 1066. From around the year 1100, we see the development of a native language in Britain made up of the French of the new ruling class, the Latin of the Christian Church, and remnants of Old English spoken by the common people. There is as yet no standard English, and different regional dialects vary wildly all across the nation.

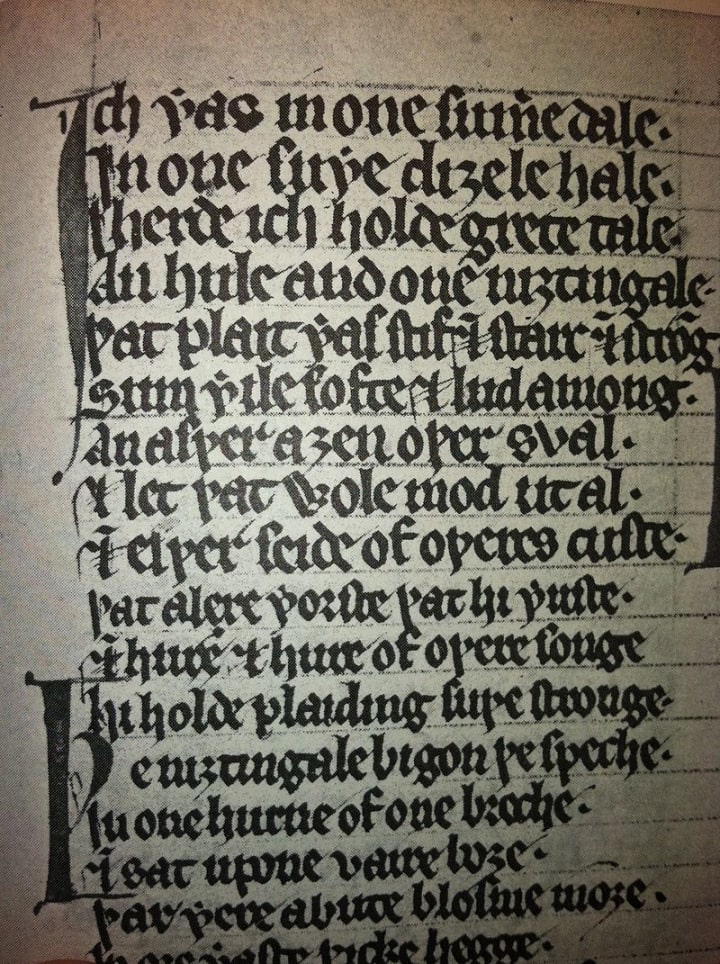

The Early Period of Middle English runs from roughly 1100 to 1300, and its most significant text is an anonymous long poem titled The Owl and the Nightingale. An era of somewhat greater literary diversity follows from the end of the Twelfth Century to around 1500, which is usually designated the Later Middle English Period. It’s here we find the Fourteenth-Century poems Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Pearl, both written anonymously and some believe by the same poet. Many of the first known names of English literature also begin to emerge at this time. These include Sir Thomas Malory, of whom we will hear more later, and William Langland to whom is attributed the poem Piers Ploughman (c. 1370). Above all else, however, the Later Middle English Period is also the era of Geoffrey Chaucer, now considered the father of English poetry.

2) The Arthurian Legends

During the Middle English Period emerges perhaps the greatest of all British legends: the story of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. The epic poem Beowulf occurred earlier, but although it was composed in Britain its influences are mainly Scandinavian and German. King Arthur therefore is considered by many to be the first home-grown hero of the British Isles. Unlike Beowulf, however, there is no single text of Arthur’s story. Rather, his is a legend we can follow as it gradually takes literary form, over a series of diverse written accounts spanning the Twelfth to Fourteenth Centuries.

It is not known whether there really was such a person as King Arthur, but if he existed, he would seem to have some kind of Welsh warrior-chief from the Sixth Century AD. His tomb is shown at Glastonbury Abbey in Southwest England, on the border with Wales, but experts do not consider it to be genuine. What is certainly real however is the literary Arthur who exists in the collective imagination, informed through a collection of accounts known as the Arthurian Legends.

According to these tales, King Arthur was the mighty protector of Britain and the noblest hero the country ever knew. The story begins in a time of darkness when Britain was without a King. In London there magically appeared a sword, embedded in an anvil that sat atop a stone. It was prophesied that he who was able to pull the sword free would be the rightful ruler. The strongest men from across the land tried one by one to free the sword, but they could not so much as move it, until a mere boy called Arthur Pendragon drew the sword from the stone and thereby became King Arthur.

Arthur’s teacher and mentor was Merlin, remembered as the wisest and most powerful wizard of all the ages. We must come to our own conclusions on the plausibility of this, as with any legend which handles the subject of magic as if it were real, but it should be borne in mind that if there was a King Arthur there may well have been a Merlin too. In superstitious times when most ordinary people were uneducated, scientific or academic knowledge was often revered by common folk to the point where it came to be regarded as supernatural power. The myths that later surround individuals usually embellish or exaggerate their abilities.

At any rate, most versions of the story tell us that through Merlin’s guidance King Arthur was was led to the mystic sword Excalibur, which he claimed from the goddess-like Lady of the Lake (in some accounts Excalibur was the sword that Arthur drew from the stone in his youth). He then founded the court of Camelot, where he lived with his Knights of the Round Table. They were a holy order who followed a strict code of honour, and defended Britain with sword and shield.

However, even as the Knights of the Round Table fought against enemies from without, Camelot was being torn apart within. King Arthur’s wife, the beautiful Queen Guinevere, fell in love with his most trusted knight, Sir Lancelot. Their extra-marital affair was the beginning of the end for Arthur, for what man can fight on when his heart is already broken? In final battle with his evil nephew Mordred, King Arthur fell, and Camelot was destroyed.

Arthur crossed by boat to the Island of Avalon, there to die from his wounds. His final command was that Sir Bedivere, one of the last of his knights, should return Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake. This he did, and it is said that when England’s darkest hour is at hand, King Arthur will return to reclaim Excalibur and defend the country again. That is why we call him “The Once and Future King.”

The earliest surviving Arthurian Legend is Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (which in Latin means “History of British Kings”), written around 1138 AD. This is the first appearance of King Arthur and Mordred. Next is the Norman poet Wace, whose Roman de Brut (French for “Romance of Britain,” completed in 1155) introduces the Round Table and the belief in Arthur’s resurrection. Another French poet, Chrétien de Troyes, wrote his Lancelot around 1180 which develops the story of Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere.

The first Arthurian Legend written in English was titled Brut (meaning simply “Britain”), a verse history composed in the early Thirteenth Century by the priest Layamon. Then from the 1220s comes another important group of Arthurian Legends, written in French by several different anonymous authors and known collectively as the Vulgate Cycle. The most important English prose version of the legend however is Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (“The Death of Arthur”), completed in 1470 and published 1485.

3) Back to Reality

Outside the fictive realms of literature, the Later Middle English Period saw the beginning of vast changes that would throw the British social and political climate into turmoil for the whole of the 1400s and everlastingly shape the course of England’s history. It began in 1377 with the death of King Edward the Third, one of that nation’s greatest monarchs, who had outlived his eldest son by a year. In accordance with English law the crown therefore passed instead to the late Prince’s eldest son, Edward’s grandson, who became King Richard the Second.

One of the King’s other sons was named John of Gaunt, and he had a son too. This was Henry Bolingbroke of the House of Lancaster. He and his cousin Richard were the same age and had been friends as children, but when they were men they became enemies. Ultimately Henry Bolingbroke, angry at King Richard’s treatment of his side of the family, led a revolution and successfully seized power from the King. In 1399 Richard was forced to hand over the English Crown to Bolingbroke, who made himself King Henry the Fourth. King Richard died in his cousin’s dungeons the following year.

No King since William the Conqueror in the Norman invasion had taken and held the English throne through war. Henry interrupted an unbroken line of hereditary succession his grandfather had battled to preserve, and which had lasted for more than three hundred years. Henry the Fourth’s son and grandson became Kings Henry the Fifth and Sixth respectively, and continued the Lancaster dynasty for two more generations.

Sadly though, the violence wasn’t over yet. In the reign of King Henry the Sixth, a man named Richard of York made a claim of his own to the English Crown. York was descended on his mother’s side from Lionel Duke of Clarence, the third son of King Edward the Third. As John of Gaunt, father to King Henry the Fourth, had been younger than Clarence, York argued that that made him the rightful heir to King Richard the Second. So began the Wars of the Roses, as York’s faction and the supporters of King Henry battled for the throne. Richard of York actually died in the fighting and was never king, but his faction triumphed, and in 1461 his eldest son became King Edward the Fourth. The Yorkists would remain on the throne until 1485, of which more in its place.

4) Printing comes to England

During the reign of King Edward the Fourth there occurred a most significant development which would play a major part in Geoffrey Chaucer’s fortunes as an author, even though Chaucer himself had been dead for three-quarters of a century by then. William Caxton, who had witnessed a new invention called the printing-press while he was in Europe, introduced this technology to England in 1476 when he set up his own publishing business in London’s Westminster. For the first time, books in Britain could be mass-produced and circulated on a national scale.

The first book Caxton is known to have published was Chaucer’s greatest, The Canterbury Tales, which was subsequently reprinted in 1492 by Caxton’s successor Richard Pynson. With publication the English language began to be standardized at last, for now that it was possible for books to be produced in such number that the whole of the populace would be able to read the same edition, regional variations in dialect began to be smoothed away.

Geoffrey Chaucer, therefore, can be said to have made a very real contribution to the development of modern English. His mode of writing was one of the very first to be seen, adopted and imitated by the entire nation. That is why today, while many Middle English texts can only be read in translation to modern English, any intelligent adult who speaks English can understand Chaucer.

5) New Beginnings

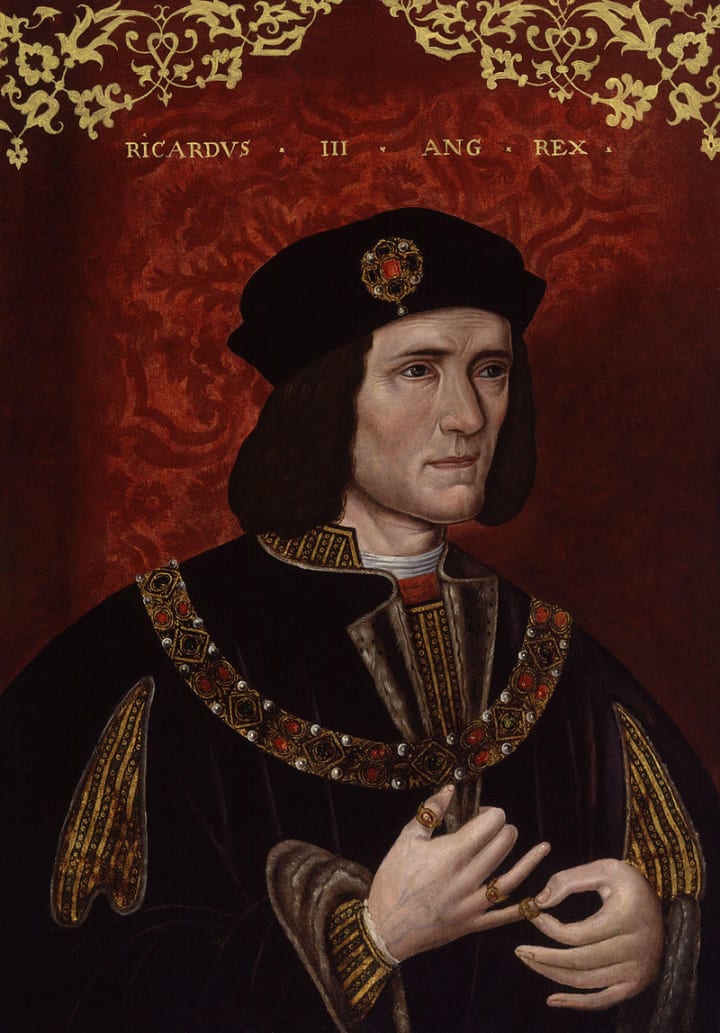

In 1485, England was further unified by an end at last to the Wars of the Roses. When Edward the Fourth died he was succeeded by his younger brother, who became King Richard the Third, and was then overthrown himself in a revolution organised by Henry Richmond of the House of Tudor. As a distant nephew of King Henry the Sixth, who had died under suspicious circumstances and without heir in a Yorkist prison, Richmond argued he was rightful successor to the throne. At Bosworth Field near Leicester on the Twenty-Second of August that year he defeated Richard and was crowned King Henry the Seventh. It was the last time a British King was deposed on the field of battle, and this date is widely regarded as the historical turning-point between the Middle English and Early Modern periods.

Certainly after 1485, new technology and newfound peace were working together to produce for the first time a standard English language. The literary implications of this are obvious, and that is one if the reasons we usually date the end of the Middle English period to around 1500. However, the development and expansion of English literature into subsequent centuries was all built upon the foundation established by those first great authors of the Middle English Period.

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (6)

I'm enjoying this article for its excellent writing and informative content.

It is truly an enlightening piece of art. I have heard about it in passing never knew all the details. It is good to know. The history is truly interesting if one ventures into it. The calligraphy from that time captures the time and effort the people have put into writing it unlike today's world where a click is all you need to send a message and sometimes the message is in such butchered english that it hurts.

I was most fascinated with the Arthurian Legends! I have always had a fascination with the Excalibur! I never knew anything else that you've talked about here so I learned a lot of new things!

Such a fascinating period. Thank you for sharing this, Doc

Quite an enjoyable read. I learned so much!! And I loved the way this flowed, well done :)

Thanks for this very informative and enjoyable history lesson, Doc!