Saddlebags and Babies

Life as a Midwife in the early 20th century

I’m up to my elbows in dirt, digging roots and tubers, ginseng, snakeroot, cohosh, all manner of medicinal herbs. Homebase is a rustic, log cabin nestled deep in the Appalachians of eastern Kentucky, just off what will be known as the Daniel Boone Parkway. My partner is a sure-footed copper-colored steed I call Penny. We spend our days and nights traversing remote mountain hollers to treat the sick, the elderly, children, and women in labor. I work for the Frontier Nursing Service based in Wendover, Kentucky.

I’m decked out in blue twill jods with matching vest, mud on my boots and my horse lathered from the exertion of climbing steep mountain passes. I collect herbs and spend time with elderly nanas who teach me old timey recipes for salves and poultices. Despite my nurse’s training and access to modern medicine, it’s the native plant knowledge that keeps people coming back. Blue cohosh’s good for bringing a baby on. Sweetflag or bitter pepper root’s good for clearing the throat or to treat stomach gas. Whitetube stargrass (aka white colicroot) helps colic and rheumatism. I know these plants intimately: I’ve learned when to harvest and the proper drying process. I know salves for nettle stings or bug bites. I treat burns, the janders, and insomnia. My patients are anywhere between the cradle and the grave.

One evening I find Thomas at my door. He’s a young man from Camp Creek He tells me Hazel Begley of Camp Creek is in labor. I know Hazel. She’s expecting twins. She lost her first baby to the pressure and I worry twins may take it out of her. I load my saddlebags and tack up Penny. Her copper coat gleams like a shiny coin in the evening light. People call this time of day ‘near the edge of dark’. Yes, it is. I mount up and ride into the setting sun. Crossing the Middlefork, water’s low, lapping Penny’s legs. Last time we had to swim this stretch as heavy rains flooded the riverbank. Penny’s ears prick forward, nickering as we trot across. We’re both relieved not to be swimming.

Hazel and Wyatt’s homestead sits in a small clearing around the bend. I smell woodsmoke before seeing plumes from their chimney guiding me in. Wyatt greets me in the yard, deep lines etched into his brow. Hazel’s moans reach my ears, low and full throated. He takes Penny and nods for me to go inside. He’s a man of few words. I remember his devastation when they lost their last one. I find Hazel inside hunched over a rocking chair, using the arm of the chair to rest her enormous belly. That’s the only enormous thing on her. She’s a mite – ropy arms and stick legs, poking out her damp cotton gown. I see where she lost her water and is trying to clean up the mess with a mop.

“Hazel, leave that. Let me take a look at ya.” I take her arm and lead her to the cornhusk filled mattress. Her body shines, perspiration dripping from her face. Another contraction seizes her. Her fingers clench mine and I encourage her to breathe in, slow and steady, then release the exhale in short puffs. She tries to copy but struggles with the pain. I wet a clean cloth and wipe her face as she lays down for me after the contraction’s subsided.

It’s a long night. She’s dilated but one of the twins is breech. I manipulate her belly from the outside, while she crouches on all fours on the mattress. She’s a good patient, willing to do what I ask despite her suffering. Wyatt watches from the corner. He coos words of encouragement and I see the love between them in those brief moments when they catch each other’s eye. His terror is palpable. He knows women die doing this. Before I walked in, he pleaded, “Please don’t let her die. I can’t live without her.” I squeezed his shoulder and nodded.

Ten hours later in the wee hours of the morning, Hazel gives birth to a boy and girl – Lester and Lucy. They’re just under six pounds, caterwauling like a litter of puppies. Lester’s lively and ready to suckle, while Lucy’s sleepy. They both have their momma’s dark hair and deep blue eyes, at least for now. I see Wyatt’s chin on Lester and Hazel’s calm expression in Lucy’s face. They look healthy, with all ten toes and good sets of lungs. I spend quite a bit of time sewing up Hazel. She bled heavily, but that seems to have been staunched and her color and pressure are improved. She’s weary and allows me to get the babies nursing, while she drifts off.

Wyatt brings me a cup of coffee and sits on the cherry wood stool gazing into the fire. He turns back, tears in his eyes as he watches his exhausted wife sleep, snuggled with his precious children. He doesn’t say much aside from thanks and more thanks. I feel his appreciation from the look in his eyes down to the mud he’s tracked in on his boots. I give him instructions for wound care and for helping Hazel get the babies latched on. He’s clumsy in his attempts, but his heart is all in. He cradles Lucy’s head as he guides her mouth to Hazel’s nipple. Bitty Lucy takes a few tries before she gets the hang of it. Lester seems to have it all figured out and gorges on her other side.

I stay long enough to be sure Hazel’s bleeding has stopped and the twins are eating well and sleeping. Wyatt pays me with a freshly butchered chicken and some ginseng – valuable commodities in this impoverished mountain community. I look forward to a roast chicken dinner later and the ginseng root is worth its weight in gold. I thank him as he leads Penny to me, saddled and ready to go. Sun shines through the trees, a hint of fall in the air as I ride back across the Middlefork towards home.

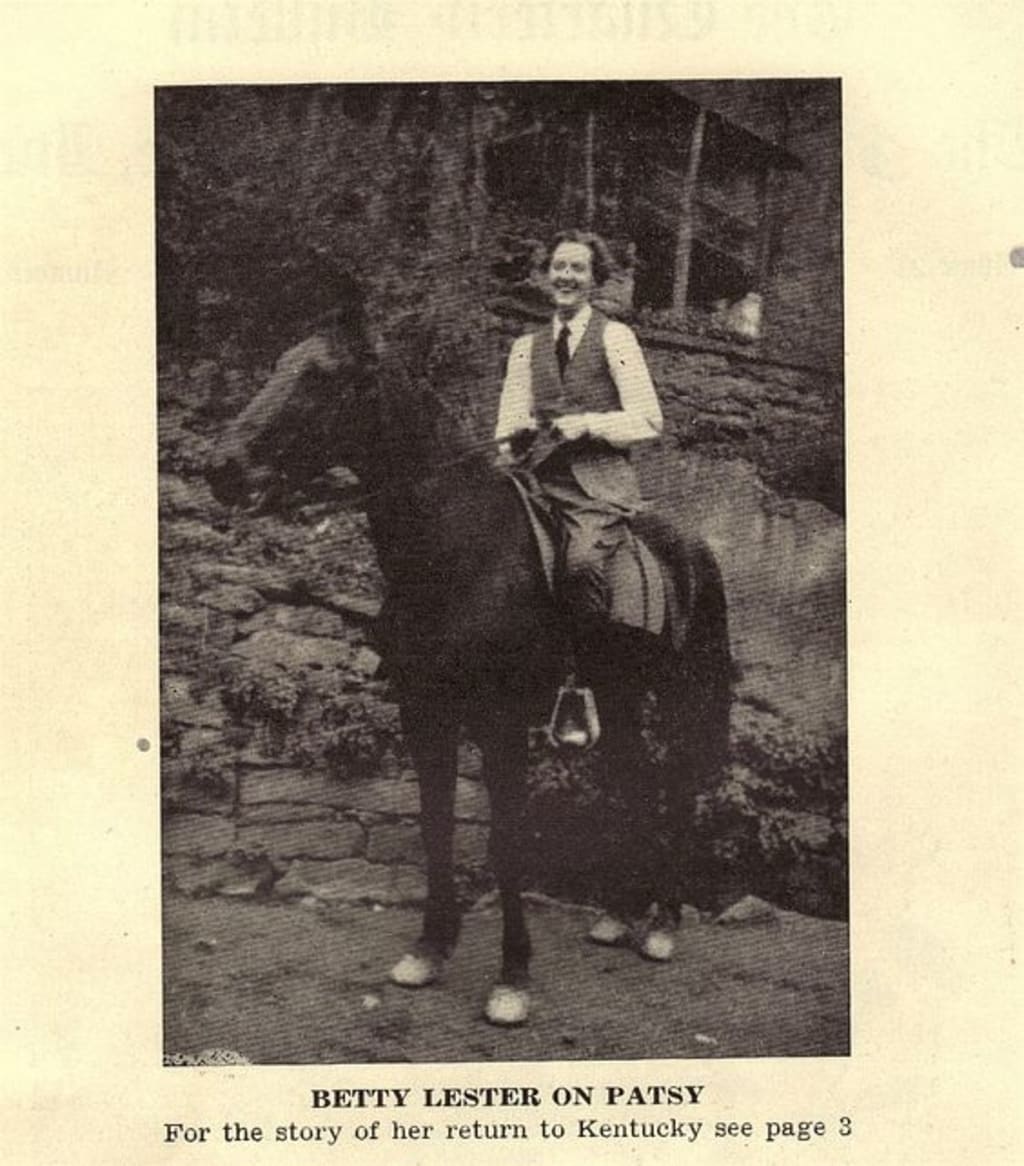

Post script: Thirty three years ago, following four years of undergraduate studies at Denison University, I moved to Hyden, KY where I worked as a literacy tutor for the Frontier Nursing Service, an organization providing health care to remote mountain regions. Mary Breckinridge founded the organization in 1925 after witnessing the impact of nurse-midwives in Russia where she lived for a time while her grandfather (VP John Breckinridge, under President Buchanan) served as Ambassador.

Despite the 65 year gap from the time I was there (1990-91) and Mary’s early days of bringing in nurse midwives from England, I too saw the benefits of access to quality healthcare. I met folks who’d been delivered by an FNS midwife. I heard stories of women saddling up in the dark, fording creeks and rivers, saddlebags flapping as they rode up mountain hollows to aid in the delivery of a newborn or to treat black lung disease with tonics and medicinal herbs.

This story is inspired by the work of those early midwives and Mary Breckinridge.

About the Creator

Cathy Schieffelin

Writing is breath for me. Travel and curiosity contribute to my daily writing life. I've had pieces published in Adanna Lit Jour. and Halfway Down the Stairs. My first novel, The Call, comes out in 2024. I live in New Orleans.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.