Stick In The Mud

Everybody in Rome Just Settle Down

Sometimes a Republic on its way to becoming an empire could really use an intractable stick-in-the-mud to run things.

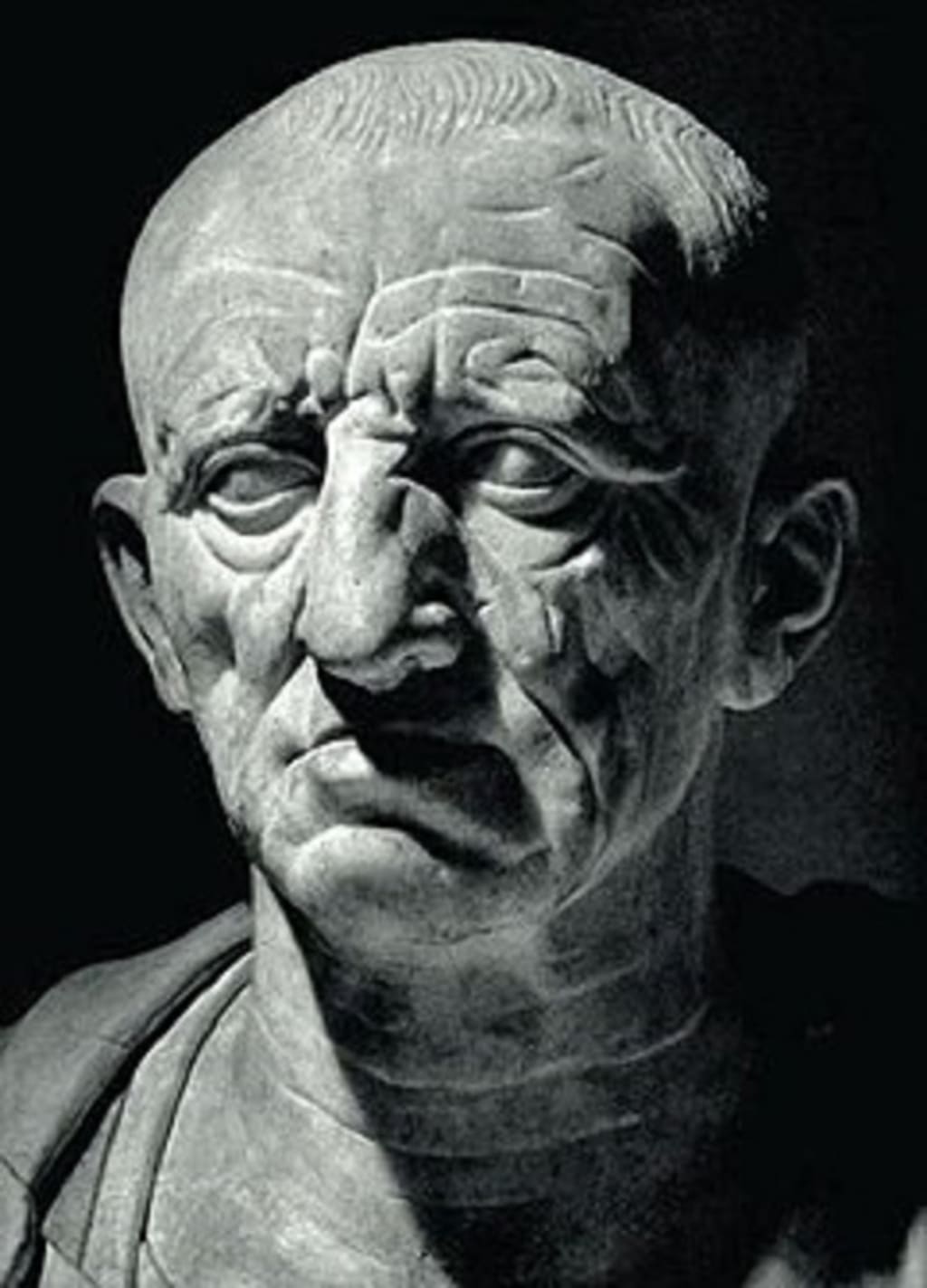

Cato the Elder was a simple fellow of simple tastes. He farmed his estate with his own field hands, dressing and eating the way they did. His penchant for tough living gained the admiration of his neighbors, who often enlisted his support to settle disputes, which sparked his career as an orator.

He came to the attention of a nearby nobleman named Lucius Valerius Flaccus, a man always on the lookout for fresh talent, as well as for men who held to the old Roman virtues of conservatism and austerity. Hellenic influence from Rome’s more recent conquests in Greece were believed to be bringing an unwelcome element of decadence and luxury into the Roman Republic. In writing a guide to better living for his son, Cato wrote that the Greeks were “a worthless and unruly tribe.”

Flaccus accurately surmised that Cato was the poster child of Roman virtue.

With this new political sponsorship, Cato took his show on the road to the Roman Forum, where he launched a career in politics. He was appointed to several high-level positions, ending up as the praetor of Sardinia. Here he put his conservatism and austerity into practice, reducing operating costs, adhering to strict public morality, administering impartial justice, and severely punishing the crime of usury, or charging exorbitant interest rates.

There was a revolt in Sardinia during Cato’s tenure. I’m sure it was purely coincidental.

Regardless, Cato put the revolt down the way he did everything else—quickly and efficiently.

Cato was elected consul in 195 BC at only thirty-nine years old. The hot-button issue of the day was the proposed repeal of the Lex Oppia (Oppian Law), which restricted the luxury and extravagance of women in order to “save money for the public treasury.” Under this law, women were not allowed to own more than half an ounce of gold, wear garments of multiple colors, or drive a carriage closer than a mile from the city.

I can’t wait to see how this plays out.

Cato made a speech chastising the women of Rome, telling them that letting them wear fancy clothes would cause some women to feel shame and others to delight in petty victories. He said that a woman’s desire to spend money was a “disease that could not be cured, but only restrained.” He claimed the removal of the Lex Oppia would render society helpless in limiting the expenditures of women. He went on to inform them that women who had become accustomed to opulence were like “wild animals who have once tasted blood in the sense that they can no longer be trusted to restrain themselves from rushing into an orgy of extravagance.”

The women of Rome, at that moment rioting in the streets in their monochrome garments, were no fans of Cato the Elder.

The consul, tone deaf to the situation on the ground, went on to berate the hapless husbands of these angry women, telling them that they should man up and not let their wives browbeat them into repealing the law. Somehow he managed to get out of that scrape alive, probably because the law was repealed when the mob of women besieged the lawmakers and wouldn’t let them leave until the Lex Oppia was no more.

The word “Cato” means “common sense that is the result of natural wisdom combined with experience.” Whoever gave the family that surname was quite a diplomat.

He was made a censor in 184 BC, and this was Cato’s time to shine. The current meaning of the word “censorship” derives from Cato’s tenure in this office. He became the conscience of Rome, expelling Senators from their positions for moral failings. He enacted stringent regulations against luxury, showing off, and having a good time, going so far as limiting the number of guests one could have at a party. He took another swing at the piñata in 169 BC with the passage of the Lex Voconia, a law that limited what he considered an undue amount of wealth in the hands of women.

Cato the Elder, still a big hit with the ladies.

He also managed to display his contempt for all things Greek. He used his oratorical powers (and his uptight view of the world) to obtain the release of the celebrated Greek historian Polybius and his friends, who had been imprisoned in Rome. His key argument was that the Roman Senate had better things to do with its time than discuss whether a few Greeks should die in Rome or in their own land.

Cato persisted in being a thorn in the Roman side to the end of his days. No matter what speech he was giving in the Forum, he always ended it with the line, “Carthago delenda est” (Carthage must be destroyed).

Don’t like Greeks. Don’t like opulent females. Don’t like Carthage.

Gotcha.

Thanks, Cato, you giant pain in the neck.

About the Creator

Stacey Roberts

Stacey Roberts is an author and history nerd who delights in the stories we never learned about in school. He is the author of the Trailer Trash With a Girl's Name series of books and the creator of the History's Trainwrecks podcast.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.