Clichés are a dime a dozen???

Yes, but their origins will blow your mind!

Aaaah, clichés. You’d have to be as blind as a bat not to see them. They’re everywhere. I'll bet your bottom dollar you’ll say and hear many every day. That's just how the cookie crumbles.

I wondered who the first gossip was to observe that “love is blind but the neighbors ain’t,” and how the saying withstood the test of time, becoming a cliché. After some investigation, I found that clichés actually have fascinating origins.

But a quick history lesson first. Bear with me, it’s quite interesting. The word cliché originated in France, thus the accent over the 'e.' French printers used a “stereotype,” which was a cast-iron plate to reproduce words, phrases, and images. The noise these plates made sounded like a click, or “cliché” in French, so the printers adopted the term. The word eventually came to mean a phrase that gets repeated often.

When an idiom, proverb, or phrase gets repeated over and over and over until it rolls off the tongue, that's exactly the point it becomes stale, tired, easily recognizable – a cliché. I will admit though, sometimes it really is easier to say “break a leg” than “go out there and do a great job.” In a nutshell, they make getting to the point quicker. So, let's get this ball rolling.

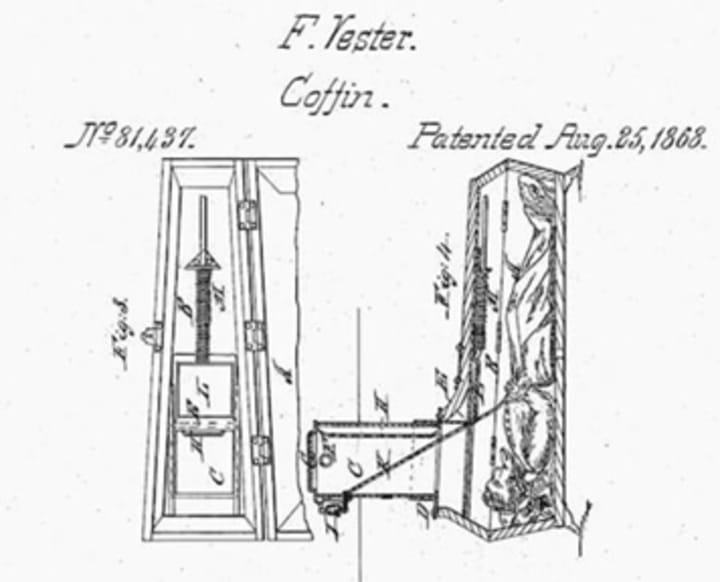

1. SAVED BY THE BELL - Rescued at the last moment from a difficult or bad situation.

You may think this saying came from the popular tv show from the 1980s with the same name, but no. It has to do with being buried, but, not necessarily with being dead. Turns out, it was not uncommon to be buried…alive.

In 1769, Lord Chesterfield quoted "All I desire for my own burial is not to be buried alive." Even George Washington was to have quoted on his deathbed, "Have me decently buried, but do not let my body be put into a vault in less than two days after I am dead."

If you were one of the unfortunate souls who appeared dead, promptly buried, and awoke to find yourself lying in a coffin, you had hope. You had hope because attached to your casket was a bell…just in case. You could reach your hand up, grab that bell and ring it! Ring it like your life depended on it!

Guards were nearby whose core responsibilities were listening for ringing bells and then saving the poor souls from a horrific death. Thus, "saved by the bell."

2. FLY OFF THE HANDLE - Loss of self-control. To react in a way that is unpredictable…most likely angry.

In those old rugged pioneer days, when handmade was the only option, whittlers, though skilled, didn’t always have the precision modern machines have today. Take whittling an ax-handle, for example. It was whittled to the point of “this looks good enough.”

Attaching the ax-handle to an ax-head, however, shouldn’t just be "good enough." It should be e-x-a-c-t. The problem was, the end-user didn’t know it wasn’t an exact fit until it was used. At times, ax heads unexpectedly flew off their handles - making them lethal.

When a person flies off the handle, and unfortunately we don’t know it until it’s too late, he or she can also become lethal. It would be helpful if there was a sound just before they unleash their wrath so we could all run for our lives.

An updated version of this cliché was conceived between 1983 – 1993 when 11 deadly rampages occurred within the U.S. post offices, with the most heinous on August 20, 1986. A postal worker was about to be fired, so he shot and killed 14 co-workers, wounded five others, and as the SWAT team arrived, killed himself. "Going postal" became the new "fly off the handle."

3. LOW MAN ON THE TOTEM POLE - To be of the lowest status.

Upperclassmen of frat houses, military, and sports organizations often tell new recruits they're the low man on the totem pole to force them to perform a multitude of nasty duties. It's a “fun” way to initiate newbies.

But like many other clichés, this one got misinterpreted along the way, thanks to radio comedian, Fred Allen. In 1941, Fred decided to use this saying as an introduction to a humorous book full of self-deprecating essays written by his friend H. Allen Smith. Unfortunately, Fred didn’t do his due diligence about the meaning, because the exact opposite of his interpretation was true. A blunder insulting the Native American Indian.

Native American Indians would use a single tree trunk, often red cedar, to carve and then paint human and animal figures to represent their tribal history and legends. The truth is, the bottom six feet of the tree was considered the most valued. The most valued because it had the widest girth and was at eye level - easy to walk around and admire.

Furthermore, while apprentices helped craft the totem pole, they were only allowed on the higher, less important part of the trunk. The bottom was where the most prominent carvings were done, and carved by the master - because of its importance.

4. WHAT AM I, CHOPPED LIVER? - A person who feels they are being given less attention or consideration than someone else.

In medieval times, the liver was considered an inferior part of an animal and generally fed only to other animals. Occasionally it was served as a side dish during a feast but was deemed less desirable than the main course. Because liver was given a second-class status, it became the object of having little importance or of being ignored altogether.

"I love being ignored," said no one - ever. Instead, you'll hear the most sarcastic tone asking, "What am I, chopped liver?"

5. GOT YOU BY THE SHORT HAIRS - To be trapped by an opponent in a position one can't easily escape.

Come on, get your mind out of the gutter. This refers to the hairs on the back of a person’s neck. The saying can be found in Rudyard Kipling’s Indian Tales from The Drums of the Fore and Aft. He wrote of the British Army occupying in India; and a soldier making an explicit reference to short hairs, located above the shoulders;

"Up my back, an' in my boots, an' in the short hair av the neck - that's where I kape my eyes whim I'm on duty an' the reg'lar wans are fixed... They'll shout and carry on like this for five minutes. Then they'll rush in, and then we've got 'em by the short hairs!"

Holding someone by the back of the neck hairs? Clearly, the enemy has been caught.

Ok, now your mind can go in the gutter. Over the years, this cliché evolved into a more vulgar, graphic, definition. It undeniably means the hairs south of the border, with the same meaning of being trapped by an opponent in a position one can't easily escape. This interpretation is not only more widely recognized, but one that is crystal clear.

6. FIGHT FIRE WITH FIRE - To respond to an attack by using a similar method as one's attacker.

In 1595, Shakespeare was the first to write about fighting fire with fire, meaning to use more extreme methods than one normally would.

The phrase became more common in the 19th century when American settlers would have to be on guard for grass or forest fires since they had no effective fire control equipment. As such, settlers deliberately started small controllable fires, called "back-fires." A literal representation of “fighting fire with fire.” A preemptive strike, if you will. Burning debris ahead of the fire would deprive it of fuel, thereby reducing the chances of it spreading into a larger wildfire. Now firefighters routinely use fire to fight fire.

When you hear someone saying this, you’ll see fire in their eyes because they are determined to meet their threat with an equal threat.

7. THE WHOLE SHEBANG - All of it.

First of all, what’s a "shebang"? Walt Whitman considered it a hut or rustic dwelling, and years later, the Marysville Tribune defined it as a house or office.

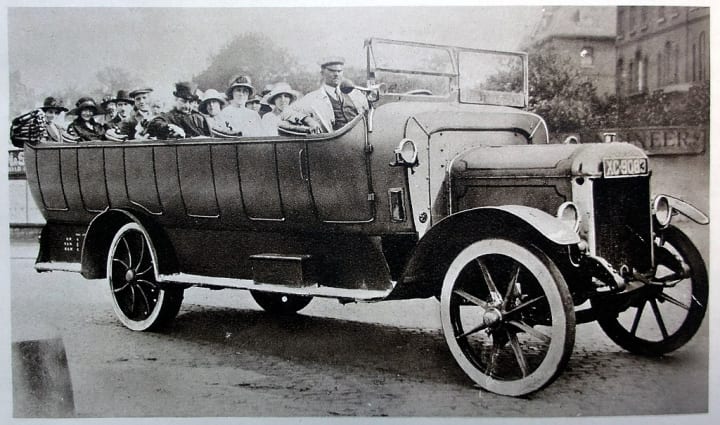

But in 1872, Mark Twain used "shebang" to refer to a form of vehicle. In Roughing It, he wrote; "Take back your money, madam. We can't allow it. You're welcome to ride here as long as you please, but this shebang's chartered, and we can't let you pay a cent."

It appears that Twain’s "shebang" was a variant of Charabanc, pronounced sharra-bang. They were sightseeing buses in Britain, driven as late as the 1920s. In the early 1800s, they were horse-drawn.

Following Twain's reference, the Sedalia Daily Democrat printed an article using shebang to mean “thing.” It was the first time it meant the whole thing; "Well, the Democracy can flax [beat up] the whole shebang, and we hope to see our party united." The whole shebang became a catchy phrase.

Today we have many versions of this including the whole kit and caboodle, the whole enchilada, the whole nine yards, the whole...I know you're thinking of more.

8. GET OFF YOUR HIGH HORSE – Demanding someone to stop behaving in a conceited and self-righteous manner.

Here's another cliché that has been turned on its head. The original reference was literal. “Mounting one’s high horse” meant to be sitting up high, on your horse; a proud, impressive, powerful position.

Elite soldiers and political leaders rode through the streets in fully adorned uniforms, riding their large horses and looking intimidating. They were so high off the ground they could look down on the common folk. Down being the operative word. To the people, the term ‘high on your horse’ meant superiority, untouchable.

By the 18th century, however, respect for people in powerful positions diminished and the phrase evolved from a literal to a figurative one. It evolved so much so that in this era when someone acts “high up,” arrogant, or superior, telling them to "get off your high horse" is meant to be an insult.

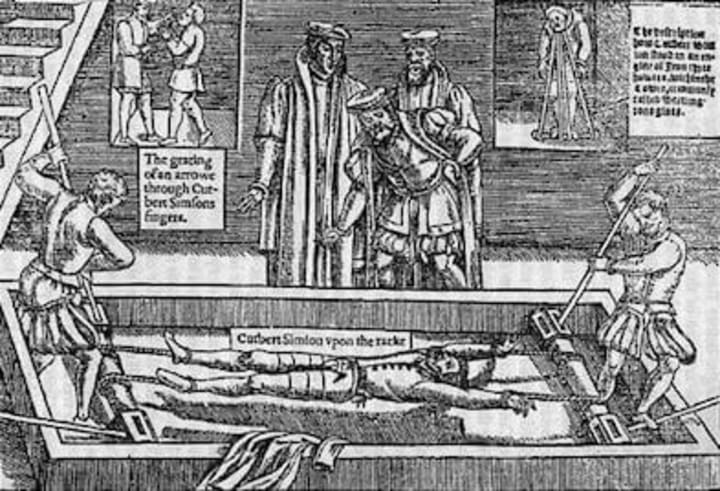

9. RACK YOUR BRAINS - To try very hard to recall or think of something.

In medieval days, the word "rack" was a noun. The rack. It was a framework to stretch things out on. Like people. And not for good reasons. It was for torturing people.

The rack was a wooden rectangular frame with straps attached to rollers at both ends. The victim would be snugly tied in, feet strapped in one end, wrists at the other. The rollers could be turned to tighten or loosen the victim. It was crude no doubt, but presumably effective in getting confessions. If not confessions, then pulling limbs from the body.

Around 1602, Shakespeare, among others, turned the noun into a verb. In Twelfth Night he wrote; "O my deere Anthonio, How haue the houres rack'd, and tortur'd me, Since I haue lost thee?”

The first use of adding brains to the mix was around 1680 in William Beveridge's Sermon; "They rack their brains... they hazard their lives for it."

The brain would be stretching and straining…to think, think, think.

So to that end, dear Reader, I ask that when you want to recommend this article but can’t remember who wrote it, please rack your brains until you remember my name, Donna Hollinger.

That’s a wrap, folks.

Elvis has left the building.

About the Creator

Donna Hollinger

Tennis anyone? Golf? Oh ya, we're busy writing.

Call me when you're done and then we can play.

I'll be outside or at my laptop...or both.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.