When My Guide Is Lost

what would it take for him to look at you that way?

Miraculously, you’ve survived. Even more miraculous though, is the survival of your best friend, who, secretly, you’ve always loved. The two of you happened to be together when the downtown area of the major city in which you’ve both lived near your entire lives was bombed. Because you were far enough outside the city you are not killed by the initial explosions but expect to be dead within the next 48 hours because you know that these kinds of bombs release colorless, odorless, and tasteless gasses that kill everything within many hundreds of miles. These are the kind of dangers you and your friends have long known about and come to terms with and there is a prearranged meeting spot. Everyone is there within a few hours, but you learn that some of your friends have already died.

You all chose to meet at a well-known hiking spot where you’d spent much time together as young adults. You are surprised to find that many other people have also chosen this to be the place they’d like to die, and the trail’s highest point, where you’d intended to go, is too crowded. Your group resolves to find a nice spot in the woods, and some of your friends are already feeling faint. You find a clearing, and all of you huddle together and shakily start taking stock.

There are long, warm embraces and words of comfort spoken. You tell each other again and again how much you’ve loved and appreciated each other and there are a few confessions of deeper yearning among your friends besides your own. After you express some huge oversimplification of the obsession you’ve had for your friend all these years, the two of you share a tender kiss, which he instigates. It’s an unclear response, but you don’t press for clarification. There are similarly polite grievances for romantic potentialities between members of your group, and then there are a few hours of waiting, passed in quiet reminiscing.

Your friends die in twos and threes. There are suggestions of burial, but you’ve brought no shovels. The slowly diminishing group moves from one place to another after every other death until it’s just the two of you, and after a few days and when all the food and water you’ve brought with you is gone, you decide that you ought to head out of the woods.

It doesn’t even take you that long, you were right near a road you have been down many times. There are cars everywhere, and he thinks it would be a good idea to take one. You pull the bodies of two girls who you can still recognize as former classmates, never really your friends, hardly even acquaintances. Now the strange gasses from the bombs have turned them a dark green, their flesh shriveling, dry and fouled.

He’s set on taking this car because he knows it to be the one with the highest gas mileage in sight, he also thinks it’s probably the most well made of all the cars the two of you could have chosen. You lay the blankets you have been sleeping on over the front seats of the car so that the fluids of the girl you sat at lunch with once don’t soak your already damp jeans. Then you drive back into town.

You get food, another, bigger car he deems adequate that didn’t have anybody rotting in it, some spare gasoline and a sturdier set of camping gear then drive away from your hometown. The roads, surprisingly, are hardly ever blocked.

Back before the bombs, you were so desperate for your friend. You’d rehearsed saying, though you’d never have really said, things like: If you’d just let me taste it once, I’d never ask you again. It would be like a treasure to me, I would remind myself from time to time that I’d had it, putting my hand gently to my throat as if feeling for a heart-shaped locket filled with clandestinely collected locks.

His tender, sad goodbye kiss in the forest had been a huge shock to you. The only kind of love he’d ever shown you previously was the love shared platonically between friends, and of course he’d never had any kind of romantic relationship with a person of your sex, and had never hinted at a desire to. You plan never to bring up your confession unless he does, and indeed the very first night, driving with no certain direction in mind, he suggests the two of you get in the backseat and that you do whatever it was you always wanted to do to him.

It’s a disappointment for you both, you lack the passion he’d hoped you’d show him, and he’s so awkward and hesitant, you can tell he’s thinking this is his only option now, and he doesn't want it in the least. Once the two of you give up, you offer that this is the first night, that it will probably get better. He says nothing. The two of you drive a little while longer around the occasional car stopped on the highway before you break the silence to say: It doesn’t have to mean anything. Of course it does, he says.

There’s a lot of time to just be quiet, apart or together. You try listening to music but they’re all sounds from a passed away world. Neither of you can figure out how to make the movie theater projectors work, and many reek from being the places people chose to entomb themselves. Same with the museums, libraries, public parks, architectural marvels, and natural wonders.

Food loses all significance, it becomes like paste and ash and the packaging is impossible to understand. The images on the bags and boxes, once familiar, become alien and bizarre. You pick up a darkened and wet box of burger patties and think of the photographer who maybe cooked one, had it set up under the lights in their studio, and snapped the now warped image that appears on the box. You wonder how much they were paid for their work. You wonder where they went to die. Then it occurs to you, there is no money anymore, no debts. Is oblivion a kind of justice?

Grocery stores are silent and stinking. Your friend can do something he’s always wanted to, and stand in the now not so cold corridor behind the cases of frozen food. You tell him, annoyed, that it only seemed magical and forbidden because he’d never had that childhood impression dispelled by having worked in there restocking the cases.

You spend days wandering in any direction, through fields and towns and cities, looking for anything or anyone. But you always meet back at whatever designated spot you’ve agreed on having found very different things, but never what you were looking for.

When the two of you do talk you complain about your aimlessness, long for your old lives, and muse on suicide. He says the two of you need to have some kind of destination. You say maybe people survived in other places, that the two of you should try heading to the coast where you might find a boat and get off the island continent. This seems as much worth trying as anything, so you start to drive in that direction.

The wastelands are littered with bodies, you take to wearing masks soaked in fragrant oils you find in a hippie shop in a city, its owner having sat until the end behind its counter. Most people, especially in rural areas, stayed at home. This is how you find the first other creatures besides yourselves and the occasional insect to have inexplicably survived. A dog barks when you enter the house of his owner, a woman who sits crumbling on her couch. The little dog jumps up from his indentation next to the corpse and stumbles around your legs. The woman had long ago had food and water dispensation systems installed so that she would never have to remember to feed the dog, the tanks were nearly empty and you refill the one for water with your own gallon jugs, knowing that there was somewhere nearby where you could get more, and find an unopened bag of kibble to empty into the one for food. You take what you want from the house and leave him to wait for his stiff friend to awaken from what he might still think is a deep sleep. In the same town you find three more dogs, one skinny and stray that won’t come near you, and two who had clearly survived the bombs, but were dead from being sick on the putrid meat of their master’s bodies. Next you see deer poking their heads out of the roadside woods. Birdsong comes at some point without you hardly noticing it.

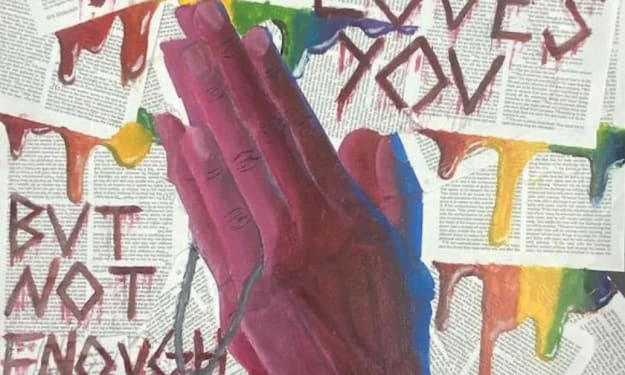

Around this time your friend starts saying that God has been speaking to him. You’re not sure what this means. You’d always thought of him as smarter, better equipped for life, a natural leader whose confidence and insight were always valuable. Now you start to see tendencies you’d previously only glimpsed get swollen and agitated. You start to suspect he’s losing his mind. He starts to take impractical items from houses and stores. You wonder why until you find him making shrines, at first just near your campsites, then everywhere. He starts growing a beard, wearing robes, intermittently fasting. He finds a big stick and starts using it as a staff. He spends more and more time alone and talks to himself around you. You start to suspect he regards you with contempt for not having heard the same message. Eventually, he says two cars would be smarter and jokingly you say: where’s the romance in that? He looks at you piteously and says what do you need romance for? You burn all your notebooks and think little of the scribblings therein. It’s only as you're watching them shrink and curl that you remember the outline you traced once, many years before, of the key your friend had given you to his house so you could let yourself in any time.

For the rest of your life, you will wonder if God really did speak to him, and not to you. If he was truly chosen, and not you.

You arrive separately at the coast and set up your own camps, though the two of you are still seldom more than a mile away from each other. He seems to occasionally be checking to make sure you’re still there.

Then it comes roaring low over the cliffs: a plane that bears the internationally recognized symbol of peace, you wonder if it truly is flying to bear this message. You are glad that you are not the one who has been put in charge of whatever the new world will be, you wouldn’t know the first thing about how to run it.

The two of you are rescued deus ex machina style and taken to a distant settlement where other survivors have been congregating. Your friend goes on to have a very lucrative career selling the book he writes, which is quickly regarded as a new kind of sacred text. You’re dismayed to see that as people rebuild, they try only to make things as much like they were before as possible. People just wanted their old lives back, and didn’t dream of new ones. They printed new money, and set up all the same old systems of commerce and government. They wore outdated fashions and did things like build exact replicas of old buildings and houses. The miracle did not inspire them.

About the Creator

Pat McNabb

poet on Coast Salish & Duwamish land

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.