The Loft

A horror short-story

The mirror showed a reflection that wasn’t my own. It showed me a man that was tired and haggard, suffering the toll of his mother’s funeral. And that much was true. I was tired, and no longer able to face condolences from people who probably thought I was better off without her.

But that face in the mirror did not feel like mine. And all my life, it never had.

When I was a child, my mother told me, Peter, your father has schizophrenia. She claimed that was why he’d left us. She also told me that it could be inherited, and that I could expect it to claim me, one day. You can imagine how that kind of pronouncement goes down with a child. All through my youth, I was certain that I would be next. That the disease was coming for me. That kind of knowledge seeps into every part your life, making you doubt your own reality — which, ironically enough, is a symptom of the disease. Even when I was at uni, studying genetics, there were days when I thought to myself, What if I only think I’m studying genetics. What if I’m just coming to this university and everyone is putting up with my presence, and the whole thing is a delusion? And then I began to wonder if wondering meant that I was becoming paranoid: another symptom. Round and round.

But in the end, it wasn’t true. At least, not true of my father. I learned this when I was old enough to start wondering where he was. Who he was. So, I found him. It turns out he was a drunk. He had arms covered in bad tattoos and a voice like sandpaper. And he wasn’t remotely interested in me or what I’d been up to. At first, he was convinced I wanted money, even though I probably had more money than him. Then he was even more afraid I might want a relationship with him. And before I arrived, I had. After about ten minutes, however, it had become clear that I no longer wanted any such thing. All the same, I stood my ground long enough to ask him about his medical history, and to ask if he was managing the illness. And he had no idea what I was talking about.

—That’s fucking rich, he said. It’s your mother that’s sick. You two ought to stay away from her.

My wife and I had only been married for a few months at the time. I didn’t remember telling him about her, but the “you two” made it clear that he knew. I wondered if he’d secretly been keeping tabs on me. I was his only child, after all. But I found it hard to imagine he had ability to manage such a subterfuge.

The worst part of the meeting was that his words resonated with me.

I knew he was right. I used to say that my mother was eccentric, but as the years went on, it became clear that she was more than eccentric. She was strange. And yes, possibly dealing with something undiagnosed. At times she could be loving and kind, and at others unhinged. If anyone had the seeds of schizophrenia, it was her. Perhaps lying about my father was as much projection as it was spite. But I hadn’t seen it. How could I? When you’re young, you depend upon your mother. She is your model of how the world is meant to work. And so in the rollercoaster of her moods, at least for the first decade or so, I blamed myself for anything bad. I thought unpredictable road trips, and weeks where we ate the same meal over and over were normal.

There was nothing I was ever able to do to make her see a doctor, even when I was old enough to move out. At her best, she complained that she didn’t feel comfortable with them. At her worst, she said they were quacks and charlatans, and she would rant about the many ways in which a doctor might try to kill her slowly with pills.

I was the one that ended up speaking to therapists. I told my psychologist about my problem with mirrors. How I avoided them or covered them if I could. Naturally, I had them in my house out of necessity. Everyone has to brush their hair and look presentable. My wife knew how I felt, of course. And it worried her for a time. But luckily for me, it became a kind of quirk she could manage. We had a variety of mirrors that slide out of sight or were covered when not in use. And that worked okay for both of us.

Here is what it is like: When I look into a mirror I see someone that looks exactly like me, but is not me. That is the best explanation I can give. I know that the person in that reflection is me — he looks like me, moves like me. But I feel in my bones that it is someone else. Not a reflection, but a figure standing on the other side of the glass. I don’t get this effect from videos or photos. Only mirrors and other reflections.

When I told my psychologist, I had put it off for so long that I had become electric with the fear that this was schizophrenia rearing its head. But she didn’t seem to think so.

—It’s possible, of course, she said. It’s possible that this is a low-level symptom. But because you are managing it, and because it has not changed or worsened over the years, and it is so specific in scope, it seems like something else. I’ll do some research. It resembles body dysmorphia, in some ways. The sense that you don’t belong in your own body. And yet, you don’t feel this way when you look down at yourself, at your own hands and legs, right? Without the mirror?

—No. Just in the mirror.

—There may be traces of a phobia, perhaps. But, Peter, if it is not impacting your day-to-day life — outside of worrying about it, of course — I don’t see any reason to prescribe anything right now. But we will keep an eye on it, naturally, and see if anything changes.

When I’d maxed out my insurer’s allowance for therapy, I stopped going.

My mother died of a stroke. They’d found her collapsed in front of the full-length mirror in her bedroom. The house had been my grandmother’s before it was ours, but she had passed on before I was born, leaving me and my mother to tramp around in a house too large for us.

It was no mansion. Just an old row-house in south London. It was narrow but deep, with two floors and a loft for storage. I was always fascinated by the loft, but my mother would never let me go up there. She used it frequently, carrying things up or taking them down. But she told me the floor was unfinished, and I would crash through the ceiling to my death if I put one foot wrong. And that was graphic enough to keep me from loft exploration, even in my teen years.

Now she was gone, and it was down to my wife and I to deal with the house. We had gone round and round whether or not to sell it. In the end, we realised it was worth eight-hundred thousand pounds. That was enough to pay off our own mortgage and leave us some for a rainy day. And I had no particularly fond memories of the place. It wasn’t going to be hard to let it go

And so began the job of going through my mother’s often scattered and strange belongings and getting rid of them, or, in rare cases, keeping them. It was tedious work. Made all that much stranger by some of the things we found — a flute that had been covered in some kind of short fur. (If my mother had a single musical bone in her body, it was news to me.) There was an entire set of plates with bulldogs on them. These, I could only imagine, had been my grandfather’s, because they looked nothing like anything mum would have kept. There was a rusted horseshoe caked in dirt. The list went on.

I had taken a break from the sorting, and sat on my mother's bed for a rest. The large mirror she’d died in front of dominated the room, and as much as I tried to avoid its gaze, it was difficult not to glance at it. There he was. That person that was not me. The illusion felt stronger than usual, much stronger, and I attributed it to the stress and emotion of the last couple of weeks. I sat staring at myself — something I had not done in years — studying that face, that body. My hair had thinned. It was the colour of straw, and not far from the texture of it as well. The lips thin and bloodless. My eyes ringed with circles.

The image stared back and then heaved a soundless sigh.

I started and sat forward. Had I sighed? I didn’t think I had, but I must have. I leaned closer. The face in the mirror seemed to be happy. Happier than I felt. Was this my face? I grimaced, and frowned and stuck out my tongue, and the mirror did the same. But when I relaxed back to what I felt was an unsmiling face, the image in the mirror again had the trace of a smile. And more than once I had the impression that the eyes, when I looked at them, took just a little longer to meet mine than they should.

My wife brought me out of my reverie, shouting:

—Peter, do you have the key for this?

She was in my old bedroom, now turned into a guest room — a change I could not comprehend, since my mother had never had guests aside from us. But I suppose it was better than having June lie in my childhood bed surrounded by posters for Snow Patrol.

In the tiny closet next to the fireplace, she’d found a locked briefcase. I had never seen it before.

—How do we open it? she asked.

—No idea. I haven’t seen any keys. Only the door and window keys.

—What do you think is in it?

—God knows. I just hope it’s not something from the taxidermy.

In the end, we found a screwdriver and simply pried up the lock. It gave with a snap, and the case fell open. To my relief, it was filled with papers. The house deed was in there. So that was good. There were a few bills, whether paid or not, I had no idea; bank statements; a few letters from various sources.

—Oh, look! said June. I’ve found your birth certificate.

She held the yellowing paper up, and as it slid between her fingers we noticed there were two.

—Two copies. That’s thorough, she said.

I took them from her and read the top one. Sure enough, there it was. Birth of Peter Lionel Whitsun. St. Mary’s Hospital. The twelfth of November. My mother and father’s names printed there. I had always hoped that it would show the time of my birth, but it did not. I flipped to the second one. It was identical. And I was about to put them both aside, when something caught my eye. A misprint, perhaps. The second one had the name Jonathan Serge Whitsun. I stared at it again. Every other detail was the same. The date, the parents, the hospital. Only the name and the registration number were different. What did it mean? Had they changed their mind about my name? Issued a second birth certificate?

But there was another possibility — one that rang true as soon as I understood what I was looking at. The truth I had always known without knowing.

I was a twin.

There was a clatter from upstairs in the attic, followed by the sound of pattering feet. Rats or mice. But it made the both of us jump.

In my mother’s bathroom, brushing our teeth before bed, we were still shaking our heads with the shock of it. And yet, I think I had always known.

—What do you mean by that? June asked.

—I think I always felt like there was something missing in me. Or like I wasn’t quite complete. I just ignored it. I always thought it was just another quirk, you know? That I was that weird lonely kid, always on his own. I always wanted a brother, but it was more like I always felt I had a brother and he was just … away. You know?

—No, I definitely do not know. That’s bizarre, Peter. I mean, even for you.

—Cheers for that. Oh! My father knew, didn’t he! That’s why he said “you two.” He didn’t mean you and me. He meant me and Jonathan.

I spat toothpaste into the sink.

—He thought I knew about him, I said.

—You should go to the hospital. They might have other records of it, June said.

I looked into the bathroom mirror, and the reflection stared back. Then it glanced at June and back to me.

June shrieked.

—Jesus-fuck! What the hell was that? How did you do that?

—I didn’t! Oh, god.

Panic had its claw round my throat. But through my racing pulse, I realised what had happened.

—Wait. You saw it? You saw it move?

—Yes!

Her face was white. Panicked. So was I. Nothing like that had ever happened before. Not so clearly. But now ... now I knew I wasn’t insane. It wasn’t schizophrenia or a phobia or body dysmorphia.

—We need to go home now, she said. Now!

—It won’t matter. This is what it’s always been like with me. The mirrors. This is just the first time anyone else has seen it. And the first time it’s moved so obviously.

—Peter, I don’t care. I want to be home. Now.

And so we went home, and June did not open any of the mirrors that night. And neither of us slept.

At the hospital, they did in fact have records. And yes, they told me. Two healthy twin boys born that day to Mrs Whitsun. Identical. No complications. The mother a little dehydrated and distraught, stayed for one night. No other medical records, not that they could have shown them to me. But they were understanding of the situation, and did a search. They did not have any further information on the twin named Jonathan.

Before leaving, I went into the toilet and stared at the figure in the mirror. Again, he seemed pleased. Happier than I felt. A mischief played around his eyes, but if they flickered in any directions they shouldn’t have, I didn’t see.

I didn’t want to return to my mother’s house. And June simply refused. I couldn’t blame her. I had been living with this for years, and even I was now living in a darker place. I was strangely happy to have learned that I was not losing my mind, and happy to learn about my missing twin, if only because it filled a kind of gap that had always felt like it was there. But the mirrors were worse now. Something had changed, and the reflection was not merely uncanny — it was unpredictable. Searching for something. Yearning for something.

I continued selling and donating the objects and furniture from the house. The mirrors watched me, judging. Sometimes pleased, sometimes frowning. And so I gave them away, too, on social media sites to whoever wanted them. I was sure to cover them and stand out of the frame, if the person wanted to check it before taking it away.

The large mirror in the bedroom was last to go. As I approached, I took a breath and stared into it. He was there. Jonathan. I knew it was him. All of those feelings made sense now, and it was clear that I was looking at my twin. He followed my movements with uncanny-perfection, but after a moment he began to blink at different times. Then he raised one hand and pointed upward.

—What the fuck do you want? I said.

And he mouthed it back simultaneously, still pointing upward. Both my hands at my sides.

I threw a cover over the mirror, and carried it down the stairs and out to a waiting van that had come to pick it up.

The house was beginning to feel free. Most of the furniture was already gone. All of the mirrors were gone. I did not know what would happen when all this was over. More therapy? If that thing in the mirror was Jonathan, then surely Jonathan was dead. And if I was being haunted, well, how did anyone deal with that? Would it ever end?

There was the rattling of tiny feet in the loft again. I was going to have to go up there soon. I had no idea how many things had been stored away up there.

But my phone rang, its tone echoing through the empty the house, and when I answered, it was not a voice I recognised. It was a woman with a booming east-end accent.

—Is this Peter?

—Yes. Who’s this?

—It’s Rebecca from Children’s Social Care. You alright? Listen, so I was contacted by Wendy Roberts down at St. Mary’s, and she told me about your situation. See, I remember you...

—You remember me?

—I was there. When your mother took you home, she was struggling, because your father left, right? So, they sent me in to check up on her. And then again, after your brother died. Poor little thing.

—So ... so, what happened?

—Did she never tell you?

—No.

—He drowned, love. In the bath. Your mother, she was run ragged. Fell asleep whilst trying to give you both a bath. Little Jonathan, he just slipped under. Right there in front of you. Poor little tyke. Of course, you were too young to understand what was happening. But your mum, she woke up and found him like that, and then called me a few days later for help.

—Do you know what happened to him. To Jonathan. Is he buried somewhere?

—Oh, I can’t say. In cases like these, she’s probably had him cremated. That’s the usual. But you’ll have to try the cemeteries maybe. Sorry I couldn’t help more. But I thought you might want to know the situation at least.

—Why did she never tell me this?

—Don’t know. Some people just think it’s easier on the little ones to not tell them. And sometimes when they’re older, it gets even harder, because you have to explain why you didn’t tell them in the first place. Vicious circle, innit.

We ended the call, and while I was grateful to know what had happened, everything had become even darker. There were shadows in the room that had not been there before. I had watched my brother die right in front of me, and I never knew. And he has been there with me ever since. Watching. Waiting.

A scratching from upstairs reminded me that I had to deal with the loft and its rodent problem.

The trap door was wide for a row-house. Often they would barely allow a slender person to fit, but this one had been made wide and spacious to allow storage. I could remember my mother pulling it open, and I would watch the ladder extend magically downward.

I opened it, but the ladder required some coaxing. It came down with an unpleasant grind of metal, but felt solid enough. So I lit the torch on my phone and ascended into the loft’s dark mouth. There was a single bare bulb hung above the door, and I pulled the string.

The loft was not at all as my mother had described it. The floor had been finished with plywood. Not a fine finish, perhaps, but there was no danger of falling through the ceiling. I groaned when I realised how much work was still ahead of me. The loft was filled with disorganised boxes, some new, some slumping into decrepitude. It was going to take another week to go through these things.

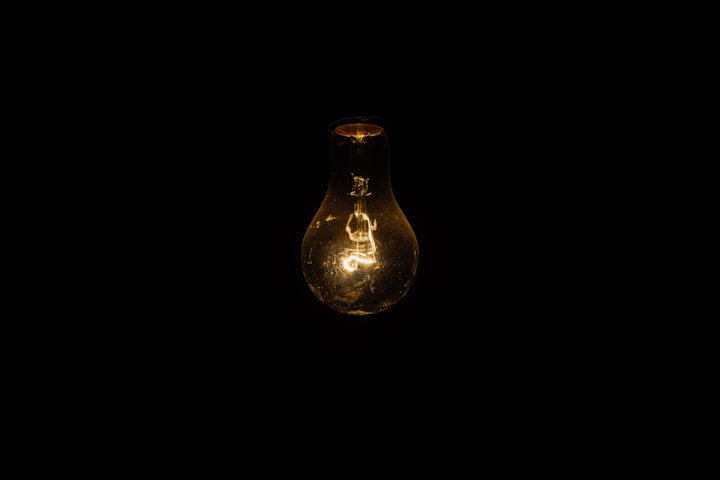

I panned the light around for a little extra illumination and saw a kind of flash at the far end of the loft. A reflection. Another mirror. I stepped over and around boxes, and when I was almost to the far wall, I found a second bulb and pulled the string. It lit with a dim buzz, bathing the area in yellow.

In front of me was a standing-mirror that came up to my chest. And in front of the mirror was what I could only describe as a shrine. In a rough semicircle, there were the stumps of candles burnt down to the floor. There, too, I saw a dusty toy rabbit with button eyes. A blue baby’s dummy. A plastic toy like a rattle. And in the middle of all this was the thing I did not want to see. The thing that made my skin crawl.

It was small. Just a tiny bundle swaddled in a blanket.

I looked up, and Jonathan was there, in the mirror. He was wide-eyed, staring back. Almost afraid. But then I probably looked exactly the same. We stared at one another for what seemed like an hour, then I saw Jonathan nod. It was almost imperceptible. And somehow, he no longer frightened me. I looked down, bent my knees, and scooped the bundle into my arms, my stomach churning at the thought of it.

Now, holding it, I could see the tiny, mummified thing inside. Shrivelled and black. Preserved in some way that I did not want to understand. And I held him there, like a baby. He weighed almost nothing.

—Brother. I said. Jonathan.

I looked up again, and in the mirror he was there. Looking just like me. Holding a similar bundle. But this bundle was moving, pink and alive. He was holding me. I looked like I was screaming.

—I’m sorry, I said.

I’m sorry, he mouthed.

Then the bundle moved in my arms. I saw the head shift ever so slightly to one side, the tiny arm flex. And my fear found me. I could not drop it. Even in my horror, I could not do that to him. But I placed the bundle back where I had found it, back into that horrible shrine that my poor confused mother had built. And I fled the room, tripping over boxes, and scrambling down the ladder.

The last image I saw in that loft was Jonathan, in the mirror, still standing as if I had never left. He was smiling. Smiling as if it was finally over.

◼︎

This was submitted to the Broken Mirror Challenge. I'm not usually a horror writer, but I had to give this one a go. If you enjoyed it, have a look around my other stories. And if you like those, share, tip, or follow! Or all three if that's your thing.

On the lighter side, here are some limericks:

About the Creator

Owen Schaefer

Owen Schaefer is a Canadian writer, editor and playwright living in the U.K. He writes fiction, speculative fiction, and breezy articles on writing, AI, and other nonsense. Attacks of poetry may occur.

More at owenschaefer.com

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (1)

Overall, your story was a pleasure to read and demonstrated a strong command of storytelling techniques. Nicely done!