My mother died in the spring, on a Tuesday. I noticed a new voicemail when my shift ended, quickly forgot about it, and remembered only when the same number called again the next morning. I woke, parched and bleary, to the rumble of my phone vibrating against the dresser. I retained no images of my dreams, only an oppressive feeling of having forgotten something. I brewed a cup of coffee and drank it all in slow, deliberate sips, eyes glued to the scrolling blur of my phone screen, before listening to the voicemail.

Afterwards, I listened to it over again immediately. Then I began it a third time, but cut it off halfway through. I put my phone on the table, then picked it up again. I could hear my neighbors through the walls. Their front door thudded, and then it was silent but for the calling of the crows that flocked to the birch tree out front in the mornings. Before I called the coroner’s office back, I called my mother. The log showed that this was something I hadn’t done in seven months. It wasn’t that I expected that she would pick up and tell me it was a mistake. I didn’t expect anything. I wasn’t thinking of anything.

—

It was her. There wasn’t much more to it than that. A heart attack. She’d been old enough, but not too old. She could have lived for longer, probably, if she had wanted to. She looked like a witch, lying there in that cold room, with her long, white hair and the veins showing blue beneath her skin. There were the sunspots on her cheeks. There were her ankles and her feet. I hadn’t seen her in a long time, but still her body was familiar to me, as good as a part of my own. We had only been able to love each other physically, in a childlike way, before I had grown old enough for speech to supersede touch, and reason to temper emotion.

I left the morgue in the midst of a very quiet panic attack. It was one of those days, typical of spring, where the weather turns from rain to shine and back again in the span of fifteen minutes. It had been drizzling when I’d arrived, with a mist like breath hanging over the streets, but by then the rain had subsided and the sun was bright, refracting through the glass of all the cars and storefronts. A slick of oil down the center of the road glinted with shifting rainbows. I noticed that I was shaking, and clasped the fingers of one hand around the wrist of the other.

My mother had been saying for years that she couldn’t wait to die and go to heaven. Since I’d been a teenager, at least. That was all she’d wanted out of life: for it to be over, the pain gone, the work ended. Now she had gotten her wish. And me?

—

For me, there was twenty thousand dollars.

Few things could have surprised me more. It wasn’t an overwhelmingly large sum of money, but it was a lot more than I had. It was also, more importantly, much more than my mother was supposed to have had. She had been living on government benefits and, occasionally, money that I would send her, for years. She had used up all her savings long ago, and had even spent the money that Grandma had left me for college, all of it gone before I turned 18. I had forgiven her for that, surrendering to the tide of love and obligation, but forgiveness hadn’t, at any point, been enough to make us close.

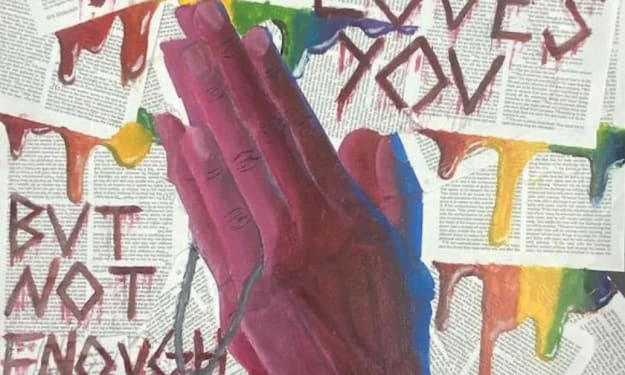

On and off, we’d be in contact, but most of our relationship was distant. She would send me photos of her pets, or forward me conspiracy theories, warning me against everything and anything: vaccines, cellphones, witchcraft, microchips, birth control, sugar. She sent me websites that supposedly showed online communications from God, the Virgin Mary, and various saints I’d never heard of. She was always praying for my eternal soul, either because I was seeing a woman or, if I was seeing a man, because I was having sex before marriage. At times we went years with barely any contact at all, blowing up at each other any time we did speak.

Although our arguments took the form of politics and religion, our issues were deeper, of the flesh. My mother was a labyrinth without an end, a riddle with no answer. The harder I tried to understand her, the more impenetrable she became. When relations between us were smooth, it was because we didn’t discuss anything but gardening and animals, the weather, the seasons. The simple material of life, those silent processes which express neither opinions nor fears, love nor hatred.

Again and again, she expressed her wish to simply die and go to heaven. Again and again, I confronted the barren reality of the future facing me: that we would never be close, never understand one another, and that when she did die, as everyone must, I would wish I had done more, tried harder, been able to reach her and, in turn, be reached.

Now it had happened, I felt nothing of the sort. I felt nothing at all, not even glad that I could start paying off my student loans and stop living paycheck to paycheck. The void that had lain between my mother and I for so many years was now only mine.

—

Along with the money, there was the contents of the apartment. She lived west of the city, out in the woods, where the birdsong lay like grace over everything and trees were just beginning to bud. I took an hour to get there. It was a tiny place, cramped and dark, with small windows. It was full of junk, interspersed with a few stray antiques that might have been worth something. I would pack things up and get rid of them in the coming weeks, but that day I came because of the cats. There were four of them. The lease had allowed only one. The landlord had been calling me every day, insisting I come and take them away if I didn’t want them going to the city pound.

My apartment didn’t allow any pets. Still, some weird compulsion drove me to take them home, along with a few boxes of photo albums and keepsakes. On the kitchen table, next to the moldering cup of coffee she had never finished, was a small, open notebook, with an uncapped pen resting in its crease. I took that, too.

It was plain black on the outside, just like the notebook I kept. Her handwriting was as it had always been—messy half-cursive, a pain to interpret. I fell asleep that night with it open on my chest, the cats each hiding in separate nooks and crannies, terrified of me and their surroundings.

When I woke, there was cat pee on the bathroom floor. In a state of exhaustion, I instant-ordered a load of pet supplies online, including two litter boxes, telling myself by way of justification that it was coming out of the twenty thousand. I opened the back door and left it that way, and slowly, one after another, the cats trotted out. Half of me hoped they wouldn’t come back. The other half, ridiculously, was looking for some sign of my mother in their eyes, the rhythm of their movements. Kindness to animals was my mother’s one enduring, inarguable virtue. She’d loved those cats with an openness and intensity that she hadn’t, perhaps couldn’t, love another person.

I called out of work that day and slept heavily, dully, collapsed in a blind, dreamless sleep. The sky outside was gray when I awoke, and rain was crashing hard atop the roof, spilling over the eaves. The back door was still open, the place was cold, and three of the four cats had found their way back inside. Two were orange, one was a tuxedo, and the last, still missing, had long white fur. On the front doorstep, half soaked, was my delivery. I fed the cats bowls full of kibble, which they ate up greedily, without offering any thanks. When I tried to pet them, they either shied away or scratched, but they must have accepted the apartment as their new home, because although they came and went, they always returned. All except for the white one.

I knew she wanted a Catholic burial, and there was enough money for one, but I didn’t know who to invite or how. Instead of trying to find out, I sat with the journal, decoding it with an obsessive devotion. It was full of the same kind of paranoid nonsense that she had often texted me, referring to politicians and the pope, celebrities and people in her apartment complex who were out to get her. Much of it was indecipherable, even once I got the hang of making out her script. There were calculations, prayers, grocery lists, doodles of flowers and birds. The cats were mentioned often, by name, but I had no clue which name belonged to which. I tried each out on the three I had, interchangeably, and was met with indifference. Slowly, however, they grew used to me, and I to them. I kept myself inside almost the whole first week of my bereavement leave, watching the cats come and go, the dogwood outside the window bloom, and rereading the journal.

I was mentioned a lot, too. In dreams, in prayers, even as if she were addressing me. She had written over and over again how much she loved me, missed me. It was as if I were the center of her world, as if we were much closer than we had been in reality. When I first realized this, I felt nothing. It was only after having read the journal dozens of times, trying to find some explanation for the source of the money she had left me, that it sunk in.

I was sitting on the back steps, just feeling the sun on my face, when the weight of her words settled in. It was like getting the wind knocked out of me.

When will she call? She will call. I’ll call her. My girl, my beautiful girl, my little angel. Lord God, have a little mercy on her.

I began to cry softly, then harder, fully, with my entire body, wracked by sobs that had been held tight inside me for the last six days. Sounds came out which I couldn’t understand, and the knot in my chest unraveled, fell apart. I cried so hard and for so long that I didn’t think it would stop, at first smudging the ink in the notebook, then clutching it to my chest the way I had not clutched my mother in years. I thought of her body, her ankles and feet. The palm of her hand against the palm of my hand, clean laundry, out-of-tune lullabies, the way her eyes crinkled when she smiled. I cried until I physically couldn’t any longer.

Opening my eyes, I saw that the sun had moved behind the clouds, and my shadow had faded into the pavement. A few yards down, looking at me from beside the chain-link fence, was the white cat. It looked dirty and thin, but its eyes were bright and curious. My breath caught, my heart thrumming fast. In its uneasy, insistent, impenetrable gaze, I saw my mother looking back at me.

—

The leasing agency found out about the cats, and gave me the choice between getting rid of them or moving out. I decided to keep them, for no good reason at all. I knew, at least, that with the twenty-thousand it wouldn’t be hard to find a new place.

About the Creator

Jaye Nasir

I'm a writer living in Portland, OR. My work focuses on mysticism, nature, dreams, sex, and the places where these things overlap.

Contact [email protected] for inquires.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (1)

Powerful. I enjoy your writing. You were the shiniest star in our fiction workshop. Fungi and Ghosts 4evr. -- Mark