The Problem of Mathematics

Most students hate maths, and we really need to start caring.

Maths. Math. Mathematics. Whatever you call it, chances are you aren't a fan. As a maths graduate turned tutor, all I can say is, fair enough.

Generally considered one of the most important subjects in a child's education alongside English and science, why is it that so many people, young and old, hate maths? Here we shall have a look at the roots of the issue, what steps we should consider to change it, and why this change is so crucial.

The Problem? A Lack of Understanding

"I hate Maths, I don't get it."

Arguably one of the most common sentences uttered in a maths class. Well, that and "when's lunch?" For years on end, this has continued to be an issue that we can't seem to get around, and it stems simply from our self-consciousness as human beings. Many people won't ask for help in front of their friends for risk of seeming uncool or unintelligent and as a result, grades go down, the issues become worse, and we're even less tempted to speak up.

As a tutor, time and time again I sit down to tackle a topic with a student, and within moments we can pinpoint one particular issue they have with it. So we focus on that. And then pinpoint an issue with the refined topic. So we focus on that. Then after a little while of rinse and repeat, we are left with one, usually pretty simple, idea that is, in fact, the cause of this entire adventure. Recently I was tutoring someone who was seriously struggling with differentiation but only in particular cases. And so we kept tracing back the issue to eventually find that she'd missed a few lessons years previous in which the class was first introduced to the concept of multiplying negative numbers. Ten minutes and a small collection of handy notes, "pairs produce plus, mix makes minus" later, and her differentiation was all sorted.

A maths teacher of mine once told me,

'You can go to university and study history, French, English, even chemistry with no prior knowledge. Granted it'll be difficult, but it can be done. That's not the case with maths. Each lecture you take will need you to implement ideas you learned when you were five.'

And while I question his views on other subjects, his comment on mathematics is absolutely correct. Imagine sitting down to an exam aged 18 if you couldn't do the basic addition you were taught aged five? As we move through our mathematical education, the pace at which we're taught new ideas continues to increase. That constant barrage of new ideas gives way to more and more "old" ideas that we need to understand well enough to build on.

So what does that mean? Well, miss a lesson or two when you're a kid and it could really come back to bite you as a teen. Especially if for whatever reason, you're not prepared to put your hand up and ask for help.

How can we fix it?

The easy answer? More one-on-one time between teachers and pupils. The practical, cost-effective answer? Sadly not that.

As a tutor, a large part of my job is to pick out the areas people struggle with, find out why, and tailor my way of teaching to suit their needs. To expect this of a teacher who is probably working with over a hundred pupils as well as setting and marking homework and exams all the while not getting paid overtime is frankly unrealistic. While many teachers would love the time to do so, our current education system just can't support it.

To accommodate for this, we could try revising how we typically spend our classroom time. Identifying how people learn is crucial to mathematics. If we can do this from a young age, then we have the opportunity to group students appropriately and offer teaching tailored to people whose brains work in the same way rather than those who just so happen to be at the same ability level at a particular time. Granted, working out the best way to sort students in this manner would take some time, but this time could then be made back as understanding the concepts becomes easier and topics can be worked through quicker.

Why Though?

So why bother? Why not just let those who are "doomed to fail" do so?

Because who would do that?! Why let people fail, let them build a hatred for a subject that they can pass on to others, when instead we could all just have a half decent time learning a subject. The further we progress into this age of technology, the more and more crucial maths becomes. STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects are at the forefront of progress and the demand for people within these fields is ever growing. We are in desperate need of engineers, programmers, chemical engineers, mechatronic engineers, ecologists, economists, the list goes on, and one thing that these all have in common is that a strong mathematical basis is essential.

Our future (and I promise I'm not exaggerating) depends on the next generation not hating maths. They don't have to love it, we just need them to not hate it enough that they don't give up. All we have to do is encourage and support and maybe keep our fingers crossed?

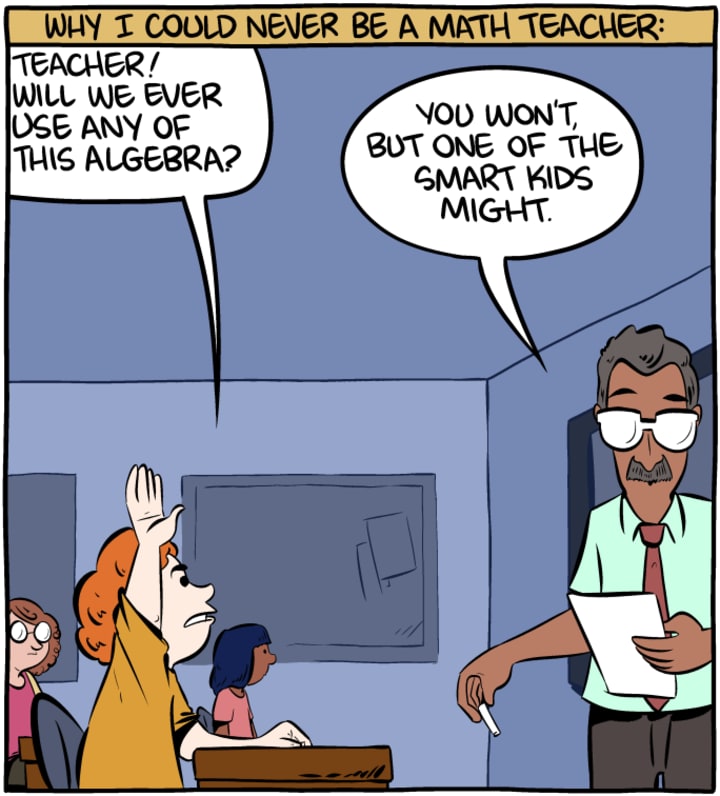

Oh, and if you hear a kid ask why they have to learn something, please don't follow this lead:

http://www.smbc-comics.com/

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.