Kokushinsan: Shadow of the Mountain Prologue - Childhood

I used Japanese Shinto. Works or something different?

Below the sharp, snow-covered peaks, an ocean of golden barely bent and ripples traveled among the fields. A dusty veil helped make those labyrinths of rock, ice, and snow seem a distant world. Up in the thin air of the Himalayan mountains, work was tedious and the yield was difficult, but at times like these, it was a better life, even in the shadow of Kokushinsan.

Himeo heaved for breath and thrust his sickle into the late summer harvest. The yellow tares toppled. He labored, sweating, his head spinning, and his arms quivering with each mighty swing. His father was next to him. He thrust his sickle in. The stocks fell. The same labor, but he did not heave for air, his head did not swim. His muscles flexed and were glossy with perspiration. Himeo, nearly a man, would never match the strength his father yielded. His dark, narrow eyes were stoic and his face unreadable as he harvested with natural intensity. Himeo tried to keep up, but his lungs burned, his heart pounded, and his legs wavered.

There was a reason for Himeo’s father’s silent and stoic nature. Yes, his father had the emotions of a stone, but the other field workers, too, were grim-faced and tense. They didn’t whisper amidst each other, and each breeze descending from the mountains, chilled by the snow it coursed over, only darkened the expressions of each man. It wasn’t until the clank of the lunch bell rang from the village below that the men made any sign of true hesitance. They stood tall from the waist-high barley. They all looked down the tiers of fields built into the hillsides toward the small hamlet. Some of the men glanced at one another, but none let their true fear betray.

Even from the highest of the barley tiers the cars in the village center were visible. The convoy was a long line of black, unwelcomed vehicles. Men in green uniforms held guns and wandered between the raised houses like aimless ants. Himeo looked to his father—who, usually, never displayed his thoughts. Now, however, his father had a glare. If that’s what it could be called. His eyes were narrower, and his frown was deeper set.

The bell continued to beat and the men returned their tools to the wagons and pulled them down to the village. Melting snow still cumulated in the shadowed nooks of rocks, bushes, and knolls. A late summer storm two nights previous. The runoff trickled onto the rutted pathways and made the downhill journey slippery, but the men navigated the mud with everyday ease. When they entered the village they dispersed to their homes. No words were spoken, only wayward looks. Himeo followed his father nearly running to keep up with his brisk pace. At the lower elevation, even though it was a short distance down, his breathing came easier.

At their house, a modest wooden and mortar home with small, high windows and a wide entryway to endure harsh Himalayan winters, a group of four soldiers stood at the base of the stairs leading to the landing and house interior. Himeo’s father gave no sign of dislike, like, or even acknowledgment of the men’s existence. Himeo was a knot of turmoil. He glanced back and forth between the men, too nervous to speak, and too frightened to stand as tall as his father did. They ascended the stone steps, slid the front door open, and entered their home.

On a typical day, the house smelled of baked barley flakes, a warm fire, and a hearty, soup ready for consumption. This time, however, with the windows shut up, the dim cool of an invaded home caused goosebumps to rise on his arms. And to his fear, in the entry room, four men kneeled at a table sipping tea. Himeo’s heartbeat quickened and his throat caught. He looked at his father who, even at the chances of the horrible news, remained unfazed.

Himeo was about to say something, anything, but his father looked at him and that was enough to keep him silent. Himeo’s mother entered the room with a steaming kettle, but when she saw her husband, her eyes widened. She shook her head. Even his mother couldn’t hide the dread the entire village held.

The waiting men followed his mother’s gaze and stood. His father stepped forward, fell to his knees, and took a deep bow until his forehead touched the thatched, tatami floor. Himeo did the same and when he came back up, their eyes were down to the ground. Submissive. Obedient. His mother, too, kneeled and set the kettle on the table, and bowed her head.

“Mr. Tsumimoto Takae,” said a lean, muscular man in military dress with a general’s decorations, “We come with news of our final verdict.”

Himeo’s mother’s lip quivered, she clenched her kimono with trembling hands.

His father bowed again.

“As you know, it has been three months since our armies invaded China. This time, we intend to take the land, which is rightfully ours. This, the world has determined, is called the Second Sino-Japanese War. We’ve come to ensure our victory.”

His father remained still.

“Behind me is Chief Priest Shigenoku. Along with him are mountaineering expert and photographer, Mr. Mugiya Dakotsu, and geologist and mountaineer, Dr. Hara Fumo. As proclaimed by the emperor’s brother, Prince Runihito, we will come upon the mountain, Kokushin, to appeal to the interests of goddess Kokuyama-Hime for success in our campaign against the Chinese inferior. Chief Priest Sigenoku has a gun blessed by the emperor and will carry it as far as the shrine and with his status shall seek access to the mountain.” An older man in the highest of Shinto ceremonial robes bowed. “From there, Prince Runihito, with the priest’s blessing, will carry forward with Mr. Mugiya and Dr. Hara with the assistance of five able-bodied men to the mountain’s summit. Atop the summit, a shrine will be erect, an offering made, and our great people will have the lands to expand and glorify our great empire.”

A heavy silence fell upon the house. Himeo held his breath. His mother held hers and was on the verge of convulsions. “Along with Mr. Tanaka Kurou, Mr. Shizuno Omihiro, Mr. Kunihiro Nagare, and Mr. Kunihiro Arou, you, Mr. Tsumimoto Takae, have been chosen as an elite citizen amidst the village. You have the blessing and duty to assist in guiding our beloved prince, our great emperor’s brother, to the summit and back safely with the blessing of the mountain.”

“No!” Himeo’s mother gasped. The men glared at her and she clenched her mouth shut, but the tears still formed in her eyes. A single droplet escaped and glided down her cheek. His father had his eyes closed, took deep breaths, and clenched his worn clothes so tightly, his calloused knuckles whitened.

“We leave immediately. We told all villagers to prepare for the journey should they be selected. Grab your supplies.”

The brevity of the situation collapsed upon Himeo. His eyes widened, and his mouth gaped open. His father, to take on the mountain, to, to… he almost screamed out but his father clasped his shoulder with a strong, sturdy hand. His father opened his eyes and glared at the floor. He shifted to stand; a dreaded hesitancy.

“You can't!” his mother cried, “The mountain is locked. The goddess lets no one summit.”

“Silence woman!” the general snapped, “How dare you speak out of line and doubt the emperor’s campaign. This is why the village was created, to appease the goddess of the mountain. We have the cause, the right, and the means to succeed.”

“I can’t lose him. No one can summit. You’ve tried before. No one has made it. You can’t. I can’t lose him.”

“Silence!” the general bellowed, but at this point, the woman was in tears. Himeo’s heart threatened to burst. His father clenched Himeo’s shoulder so tight it hurt. His eyes betrayed more fear for his wife than the expedition.

Himeo’s mother stood up and the men gasped. “I won’t let you parade him to his death. I won’t stand by and let these foolish notions of war destroy my family. He’s my husband. I can’t lose him. No one deserves to go up there!”

“Soldiers!” the general called. The front door slid open and hurried footsteps rushed in. Faster than Himeo had ever seen, his father stood and swung around.

“No…” his father pleaded but two of the soldiers fell upon him. The other two, treating the scrawny Himeo as nothing but a child, kicked him aside and fell upon his raving mother. She screamed, thrashed, and kicked but the men seized her. The other two soldiers pushed his father against the wall. The man struggled, but when Himeo was about to stand he cried, “Don’t, Himeo.”

The woman was restrained, she cried for her husband. She begged the general to reconsider, but the man narrowed his eyes and motioned toward the back of the house. “Teach this woman what it means to speak out of line, to speak against the empire.”

The men forced her back and she tried to resist. She screamed and Himeo’s father tried to push back on the soldiers. He broke free for a moment, pushed one aside, but the other jabbed his stomach with the butt end of a rifle and sent him to the ground. Spittle fell upon the tatami floor. His father resisted but was hauled back to his feet.

The rear door slid open. Himeo trembled, frozen in place. Feet kicked at the floor and door frame, and his screaming mother’s cries grew muffled. His mother cried again, but this time, she sounded gagged. There was a pause and then her screams, a pain that ratcheted through the house, torqued the air with intensity. His father broke into another fit, and for the first time in Himeo’s life, he saw his father cry. He bared angry teeth and tried to struggle.

The two soldiers reentered the room. One had his father’s pack, stuffed to the brim for a two-month expedition. They grabbed his father and forced him outside.

“Don’t worry, son, you’ll see your father again in two months. Now, tend to your mother,” said the general as the chief priest, the geologist, and the mountaineer, grim-faced, followed the soldiers out.

Himeo’s mother’s moans carried from the back. He got to his feet, his knees weak, and he fell again. He stumbled, half crawled, half walked to the back where a cold draft from the icy mountains leeched into the dim. He found his mother bent over, weeping, and rocking back and forth. Her hands were to her mouth and blood drizzled between her fingers. Himeo froze on the stone threshold to the kitchen. He looked at the ground, back up at his wailing mother, and vomited.

He stood up, his hands trembling, connected to his aching heart by two skinny limbs that did too little to protect the family. If his father never returned his family would die. He turned around and raced to the front door. He stopped at the top of the steps and watched as the black vehicles, his father inside of one of them, drove off towards the entry of the mountain.

Across the single avenue, Himeo made eye contact with Sumiya. She wore a flowery kimono and her hair was bundled up with green hair sticks. She stood at the entryway of the Shizuno family. Her younger, child-brother and her mother were behind her pale as a Westerner. Tears streamed down the girl’s face as she too watched the caravan move on towards death. Himeo’s heart ached. Even when she cried she was so beautiful, and she, too, was to lose her father to the mountain.

Before he realized what he was doing, Himeo tumbled down the steps and chased after the black convoy. Sumiya, her family, and other villagers from their doorways called after the pathetic excuse of a man. Still, Himeo ran. His lungs already burned by the time he reached the outer limits of the village. His legs wobbled as he climbed the steep hills past the tiers of half-harvested barley fields. He had to stop at the upper level. His lungs gasped for air and his head swam in liquid delirium. Tears, stringy saliva, and snot dripped from his face. He leaned against the rock and wiped the drizzle on his sleeve then continued at a weak jog up the rocky terrain where the tire tread was visible in the mud.

When the snowpack started to appear and Himeo was kicking through ankle-deep snow, the convoy of vehicles passed him. The drivers and passenger soldiers with hollow, humored eyes glanced at him as they slid by. He tightened his resolve, despite the numb hands, the burning lungs, and the nausea.

The evening hour drew upon him when he finally reached the upper slopes. His feet, numb and aching, sunk into the snow up to his knees. He broke through a patch and then raced, stumbling across the stones and the tufts of yellow-pressed weeds. His “jog” at this point was nothing more than a foppish walk.

Upon the rise of the hill, he came to the entry of the mountain. Two stone-stacked pillars stood on opposite sides of a faint foot trail. Long lines of rope were tied to the pillar tops and anchored to the ground. White paper tassels hung from the lines. At the base of the pillars were miniature, orange torii gates, candles frozen but melted from previous burns, and withered vegetables as a tribute for a Shinto shrine. The expedition had already entered. His father was gone.

Himeo was about to step through and continue his pursuit, but he stopped just before the entryway. There was no dust in the air, and the wind, a rare moment for the Himalayan range, wasn’t present. The stillness brought a silence upon the land. Trembling, Himeo stood frozen in place. The footprints of the ten-man expedition were visible in the snow. He wanted to press forward, but the fear held him back. A veil cast over the threshold of the gateway. Beyond was the realm of Kokuyama-Hime. The snow resumed its blanket upon the land and rose up with the rugged terrain. Past the gateway was a long, rising canyon topped with razor ridges and unstable snow. Above the walls of stone and snow, rising in the distance like a singular fang, was Kokushinsan. The peak stood unconquered by man.

No wind blew, but Himeo swore he heard a whispering moan echo between the ridge lines. There was a stillness, an essence of life bereft. He fell to his knees, a painful thud upon the hard earth, and tears trickled down his cheeks. The sun began to set and long shadows of the mountains and columns grew until they started to consume. The mountains turned blue, the horizon purple. It was nearly dark when a hand rested on his shoulder and pulled him from his misery. He looked up and saw Sumiya. She had a thick blanket wrapped around her shoulders, gloves on, boots, and a hood drawn up over her head. Himeo looked at his purple skin and his stiff hands. He clenched them but they only made loose fists.

She knelt next to him and placed the blanket over his shoulders. Behind them, Aoyama-san, one of the lucky men to remain behind, sat on a mule-drawn cart. With the thick fabric around him the first shiver set in, the hypothermia threatened. Sumiya waited for a second and whispered something in his ear before Aoyama-san helped her load him into the wagon. In the back of the wagon, Sumiya, concerning the parents they lost, wrapped her arms around him. They cried together.

Himeo was too tired, too cold to think, but as the wagon returned down the hill and the night drew upon them, a wind picked up. Snowdrifts picked up and swirled between the steep stone walls. The paper tassels clattered in the breeze. He could’ve sworn it was an illusion, but the snow, just on the other side of the stone pillars, in a violent tumult, tumbled and swirled and created the visage of a person; a person no taller than a child. It was gone a second later. The wagon descended the hill and the threshold fell out of view along with the distant Kokushinsan summit.

Himeo never saw his father, nor any of those men, again.

Notes:

Thank you for reading the first chapter of my mountaineering horror/thriller: Kokushinsan: Shadow of the Mountain.

Questions to consider:

How is this hook?

Originally I wanted to pull the deity of the cursed mountain from the dead Tibetan religion, Bon. Due to how little information is available (except for what is mixed in with Tibetan Buddhism, there is little known/discovered about Bon), I went with Japanese Shinto and created a cast-out goddess, Kokuyama-Hime. Sister to a real mountain goddess, Shirayama-Hime. I was too excited to write the story during NaNoWriMo, so I went with lore I was comfortable with and it actually wasn’t half bad. Does it work, or in future revisions should I pivot to Tibetan Buddhism and continue my research for clues about the ancient Bon religion and their lost deity?

Do you know any good sources on the ancient Bon religion?

Thanks for reading!

Image: Dall-E2 generated

About the Creator

Christopher Michael

High school chemistry teacher with a passion for science and the outdoors. Living in Utah I'm raising a family while climbing and creating.

My stories range from thoughtful poems to speculative fiction, fantasy, sci-fi, and thriller/horror.

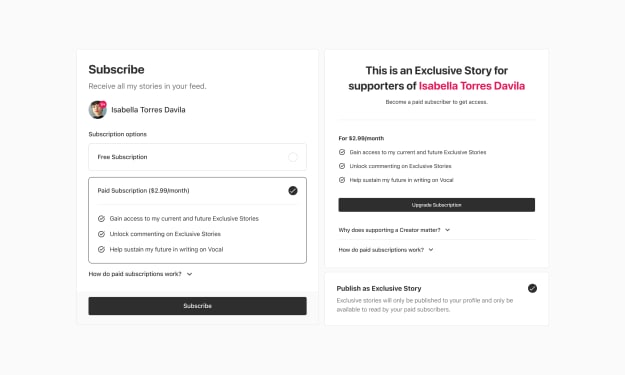

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.