Dream Fandango

Westward Expansion, Outlaw Legends, & Reframing Tiburcio Vasquez

"That weapon will replace your tongue. You will learn to speak through it. And your poetry will now be written with blood." ~ Exzebache (aka “Nobody”) to the outlaw Bill Blake, Dead Man, 1995.

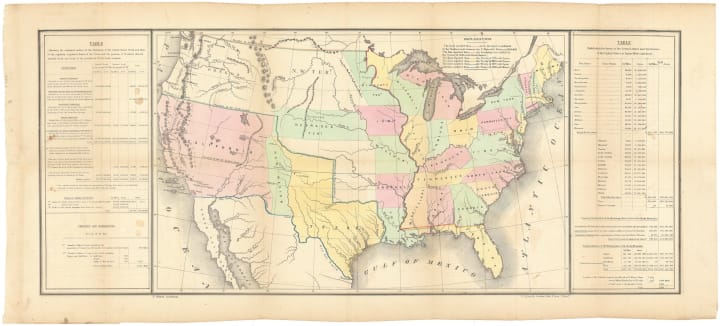

The criminals of 19th century California have become legends. From this, the study of California outlaws emerged as a resource-rich field despite near-ubiquitous practitioners’ warnings regarding this topic’s tendency towards misconception. It was misconception that caused and finished the career of Tiburcio Vasquez, outlaw to California, and it is misconception that has rule over his legend. Jean-Luc Godard’s malevolent supercomputer, ∝-60, expounds that the social-philosopher/rebel “type” will be made extinct and, what’s worse, will become legendary. Such skewed cultural myths, social legends, and folklore tales have invited an ever-increasing pool of historians to build California outlaw histories that more closely approach authenticity to extra-legal events of this era. Vasquez’ life parallels, collides with, and was informed by the shift from Alta California to the California Republic. United States expansion into the northwest territories of Mexico— Texas, the Four Corners, Nevada, and California— bore a massive and culturally manipulated body of evidence, as creatively illustrated by cartographer Ephraim Gilman in 1848. A historiographical study of California outlaws, especially Tiburcio Vasquez (b.1835, d. 1875), offers a kaleidoscopic omni-lens to help unpack the social and cultural impact, then and now, of Pacific Westward Expansion from the Jackson presidency and into the Industrial dawn of the 20th century.

In 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner presented his “Frontier Thesis,” later to become The Frontier in American History (1921,) in which he says, “The appeal of the undiscovered is strong in America… American democracy… gained new strength each time it touched a new frontier. Not the Constitution, but free land and an abundance of natural resources open to a fit people, made the democratic type of society in America.” His use of words such as “undiscovered,” “new,” “free,” and “fit,” highlight the heart of Turner’s enterprise. For Turner, liberty was a natural result of American interaction with land, while he also sought to synthesize themes of overarching Americanism “with a single, coherent story,” for a new century. Turner’s poetics bemoan “a changed world” at the end of the American wilderness and frontier with its explorers and pioneers, whom he reveres, in preparation for a new dominance by industrial globalization that promised, finally, to civilize the west for its Anglo inheritors.

Turner’s Frontier Thesis is at times environmental in discussions of water and land use, as well as more traditional in its focus on emerging national population centers, and broaches acceptable and convenient social history in discussing the developing role of the individual in American society. On frontier pioneers, “These men had means of supplementing their individual activity by… extra-legal, voluntary association… one of their marked characteristics… [With] an authority akin to that of law… [they] were… not so much evidences of a disrespect for law… as the only means by which real law and order were possible in a region where settlement… had gone in advance… of organized society.” Turner is describing a Roy Bean current that has run through southwestern history. Here, he indicates a legal crystallization carried forth by American settlers in a new land, without indictment of “evidences” to their illegality— he ties concepts of lawlessness together with the physical, social and cultural conquest of California, pointing to cattle-raisers’ and squatters’ associations, mining camps, vigilantes and lynch mobs, and other forms of informal and impromptu law, justice, and militant force seen on the California frontier and explored in greater depth through subsequent histories.

Figure 1 — Ephraim Gilman, Map of the United States (1848).

By 1940, Cora Miranda Baggerly Older picks up on these themes of law and Americanism in Love Stories of Old California with a view on Tiburcio Vasquez that is at times romantic, and in the main lacking in trustworthy scholarship. Older offers a smattering of issues at play in mid-19th century California and identifies important elements of this social culture— the mission system, Indian revolts, the gold rush, lynch mobs, horse thieves, Vigilante actions, insurrection, and resentments held by the descendants of Mexican pioneers— before introducing Tiburcio Vasquez. Older describes Vasquez’ familial links to political power in San Francisco, San Jose, and Monterey, and indicates his level of education by noting his study of poetry and guitar in “good Monterey schools.” Predating the term, Older then offers Vasquez as a social bandit who “lived recklessly, robbing rich gringos and often giving his plunder to the poor… [and who] found at every Spanish-Californian ranch a refuge, friends, and facile loves.”

Despite high praise for Older as a “thorough scholar” who “has left little for anyone else to work on,” Older’s love story provides no clues to the sources she consulted as she presents an account (very likely a semi-fiction) of love shared between Tiburcio Vasquez and Rosario, the wife and mother of two to Vasquez gang member Abdon Leiva, who ultimately testified against Vasquez at his murder trial. Older relies heavily on an analysis of changing conditions in California via the Mission system, with the briefest mention of disease, environmental, and military analysis, and transitions into the body of her work by stating, “Now for the first time women colonists entered California. With women came romance.” This serves to reveal Older’s text as an early and flat foray into the field of women’s history. A gender analysis of this passage paints the outlaw Vasquez as a volatile force working against the traditional American social structure (that of Leiva’s nuclear family) through the chaos of raw emotion. For instance, Vasquez is undone, according to Older, by his blind love for and tireless devotion to Rosario.

While Older sets up the story of the fall of Tiburcio Vasquez by indicating such larger elements of power as the Mission system, Westward economic expansion, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, she concludes on a confused note that relies on the legendary aspects of Vasquez’ life, marking with dramatic lamentations the reactions of Mexican-Californians to the death of the Don Juan of California and “their defender.” Because much of this narrative stands as unverifiable and her sourcing is nearly non-existent, Older’s narrative offers little credible new information about this era, either on gender roles in California at the time or on the factors that shaped Vasquez’ life and crimes. However, in this, Older does present a kind of color to the wider picture of outlaw studies, both to conditions present in California during the mid-19th century, as well as to the same issues of social injustice and gender roles that emerged and developed in America prior to the mid-20th century.

In 1944, the collected articles pertaining to Vasquez penned by former San Francisco Chronicle journalist and “King of dime novelists” Eugene T. Sawyer (b. 1846, d. 1924) were re-published as The Life and Career of Tiburcio Vasquez, the California Stage Robber, and Murderer. Much of this pamphlet originally appeared in articles for the Chronicle in 1874. In fact, Vasquez allowed interviews from only three journalists, one of whom was Sawyer, resulting in the 1874 publications of three similar histories on Vasquez, all featuring interviews with the outlaw being held under custody. These pamphlets, including Sawyer’s, comprise the first attempt to present the full scope of the life and crimes of Tiburcio Vasquez. In the end, Sawyer’s writing deals in the main with the spectacular, the conflated, and the newsworthy tidbits. Though Sawyer’s account reads with an air of primary authenticity, evident in his interviews of Vasquez, it becomes clear that, in the end, Sawyer’s bias and manipulation of subject are as pronounced as in the case of Older’s history. Ever fascinated by his love life, approximately 1/6 of the pages in this short collection attend to accounts, stories, or rumors regarding Vasquez’ sexual career. In the book’s introduction, Joseph Sullivan notes that Sawyer “gives to [Vasquez’s captor] Sherriff Adams a more important part… than would appear to be justified,” as a result of access to Vasquez obtained by Sawyer through Adams. Regardless of its interests, Life and Career attempts to recognize that 19th century California “Mexicans, although in the State, are out of it. They still preserve a sort of international independence, and keep their affairs to themselves.”

In this light, Vasquez— who is described paternalistically either as “a dandy in dress and appearance,” a “wily rascal,” or as “this little Spanish fighting-cock,” and whom Sullivan claims had little “trouble activating a landless Juan, Pedro, or Miguel to assist his varied tasks,”— represents a typical Californio response to American incursions, although he moved beyond convention as he employed “semi-guerilla” tactics in such expressions. “Vasquez operated in a period of stress and strain. Even the conquerors were not yet in adjustment to their environment,” Sullivan explains. He then places Vasquez into a long line of historic “redistributors”, and active respondents to “wars, migrations, [and] empire-changes,” by invoking the names of William Quantrill, John Hancock (as a rumored smuggler turned patriot), Jesse James, Pancho Villa, Jean Lafitte (as a frontier double-agent), even the “dragon pirate” Sir Francis Drake. Sullivan notes the swell of Californio and Mexican admirers of Vasquez who brought prayers and admiration (and even professed love) to the detained outlaw, as well as the exceeding courtesies granted Vasquez by his captors, an elite body of law enforcers who were present in overseeing his detention and final execution, as evidence of his import.

Sullivan and Sawyer’s approach to Vasquez (Sullivan dedicated Life and Career to the Battling Bastards of Bataan) is dualistic and born of a tension highlighted in Hobsbawm’s 1959 study of “two extreme types of the ‘outlaw,’”: “The classical blood-vengeance outlaw… a man who fought with and for his kin… against another kin… [or] essentially a peasant rebelling against landlords, usurers, and other representatives of… the ‘conspiracy of the rich’… Thus, all members of the… community, including the outlaws, may consider themselves as enemies of the exploiting foreigners who attempt to impose their rule.” Hobsbawm does not investigate American outlaws, although ideas raised in this and other of his works permeate into studies of Vasquez and southwestern lawlessness.

In recognizing a need to give southwestern studies “legs to stand on,” John Myers Myers’ The Deaths of the Bravos (1962, Boston, MA: Little, Brown) attempted to chase down “history’s unicorn.” Myers approaches frontier history as “properly one chronicle,” and his bravos “had in common… a willingness to stake their lives against whatever they wished to achieve.” Again, Myers notes the influence of legend, lore, fancy, and projection as he attempts to synthesize the travels and exploits of prominent southwestern pioneers, frontiers- and mountain men, war criminals, outlaws, and indigenous Americans. “By and large,” admits Myers, “what went on in the early days of the American West transpired while historians were looking the other way.” He notes the influence of oral tradition on histories of the West, which he claims offers as much to “formal history as do the Norse sagas.”

Myers asserts that his work is informal, although its bibliography (which “does not include the numberless newspaper and magazine articles examined…”) enumerates eighteen pages of biographies, memoirs and journals, encyclopedias, corporate, topical, regional or state histories, print journal compilations, government and legal record books, military and religious histories, Indian studies and histories, as well as local committee documents. Clearly, Myers is striking a balance between narrative and historical representation, and his book reads like a vast collection of short stories featuring the full cast of characters from the Old West (including Joaquin Murrieta, save for Tiburcio Vasquez). Myers ties together the disparate travels of Mexican and American pioneers and trailblazers, Indian leaders and raiding parties, Mormon settlers and rebels, profiteers and miners, mountain men and outlaws, politicians and military generals, and he includes a list of “Leading characters and events” that reads like a quick summary of the book.

Myers describes San Francisco’s population explosion through an influx of forty-niners, gamblers, power-seekers, and other Atlantic coast transplants, and talks of how, even in 1849, California was “confident of becoming a state. It had the assurance of gold behind it” He notes several young transplants to California who came by ship carrying lengthy criminal histories, and who nonetheless gained access to California power by sheer determination and self-organization. This reality permeated California from the cities to the mining camps, Myers explains, “The fact of people converging in quantity on an area [that] had not been legally and politically prepared for their advent… the gold-seekers… were illegally in business… The federal government had not [set] up any system of laws by which land could be held… The forty-niners… made up their own laws and, borrowing from Spanish politics, chose alcaldes… At first organized to act in civil cases related to mining, these popular courts began to handle criminal matters, too… For minor offenses they flogged the perpetrators; for major ones they hanged them… They were not a court then… but a blood-stirred crowd… A gang calling themselves The Hounds began operating. Pretending to be volunteer police… they were vicious predators.”

Myers draws out the sordid affairs of California’s Vigilance Committees, which he describes as a Whig response to legal procedures advanced by California democrats. Myers illustrates a court structure in which any and all participants, including the defendant/prisoner, the judge, and the attorneys, as well any spectators, and even the Governor, were often armed with one or two pistols and even double-barrel shotguns. From this, Myers describes the creation of “the People’s Court,” a California entity in which none of the participants carried their own names into proceedings, but were referred to by number. Despite this, and the fact that “San Francisco was bloodied… by murders whose number would have shocked Nero,” these courts were relatively ineffective in prosecuting actual crimes or criminals. Instead, early Anglo California justice conveniently served the farcical whims of those who controlled it.

Building from this, Myers addresses land issues in a chapter featuring Roy Bean, Joaquin Murrieta, as well as the “horse barony” of the Anglo “Destroying Angel,” Jack Power. Myers describes Los Angeles as “half a Mexican town” and the unofficial capital of California, and asserts that by 1852 the surrounding environs had become the “stamping grounds of a bilingual mixture of native Californians, American settlers, Mexican bandits, whites who had been chased out of gold camps for cause, and a corps of professional gamblers.” With such a colorful contingent amongst its citizens, Los Angeles boasted a regional gambling fraternity, headed by Power, and a multitude of local horse thieves, of whom, says Myers, Power was rumored to be the great orchestrator. Myers forwards a common notion of the time that Murrieta was, in fact, a soldier for Power, who owned a San Gabriel horse ranch. To this point, Myers offers, “Previously property titles had been acquired in almost any old fashion, so the move to regularize real estate ownership uncovered many overlapping claims, not to mention cases where there was no legal ground at all for asserting possession… For an unsung reason, Jack Power was one of those adjudged to have come by his ranch improperly.”

Here, Myers briefly details a rumor that Joaquin Murrieta was considered by many to be a fabrication concocted by Power, and by as many to be a real outlaw, whether from Mexico or born as a native Californio. What Myers makes clear is that “the reports which admit of his existence are alike in declaring his ferocious hatred of all Americans.” At this point, Myers redirects by stating that many thefts actually carried out by any of “numerous bandit gangs— local or operating out of Sonora—” were ascribed to Murrieta en masse. Similarly, when a Mexican head in a jar was asserted to be that of Murrieta’s, few questions were asked, and no further crimes were ascribed to the ferocious Murrieta— whether a factual character or merely a fictive amalgamation.

This historiography benefits from consideration of Alfredo Mirandé’s Gringo Justice (1987, Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press,) despite the fact that “it is not intended to be a historical work.” Instead, Mirandé seeks to compile “a single comprehensive scholarly assessment of the Chicano [in] the legal and judicial system[s] [of the American West].” Gringo Justice credits racism as “very prominent as a promoting and underlying cause” of Anglo incursion into and revolt against Mexican-held territories and institutions. Also, says Mirandé, such racism informed Anglo treatment of Californios as “lazy… riding, gambling, and “fandango-addicted” greasers.” Mirandé assesses that “the American takeover of the Southwest proved to be [both] a political and military victory [as well as] a racial and cultural triumph [for Anglos].” A “pagan” Catholic adherence is indicated as cause for Anglo-Christian concepts of Mexican inferiority, and the mandate to melt down differences is paired with a “divine imperative” to acquire more than half of Mexico, as well as, “the destruction of Mexican culture.”

Mirandé very quickly condemns persistence of “the image of Chicanos as criminals or bandits” as caused, not by inherent criminality, but from “a clash between… competing cultures, worldviews, and economic, political, and judicial systems,” from which “Chicanos were rendered landless… displaced politically and economically, but… became a vital source of cheap and dependent labor for the developing capitalistic system.” Lacking “the power to shape images of criminality” in California, “Chicanos were labeled as bandidos because they actively resisted Anglo encroachment and domination.”

Mirandé addresses the scholarship of Leonard Pitt, who states that “After a century of slow population growth, during which the arrival of twenty-five cholos or fifty Americans seemed… momentous… suddenly and without warning California faced one of the swiftest, largest, and most varied folk migrations of all time,” through the period of gold-rush, after which time foreigners outnumbered Californios “by a ratio of between ten and fifteen to one.” In his section entitled, “Evolution of the Bandido Image,” Mirandé ties the perception of “Meskins” as lawless alcoholics together with hostilities arising after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and notes Anglo fascination with bandidos while maintaining disinterest in “police abuse or denial of equal protection of the law” as guaranteed under Article 8 of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. “More often than not, the Mexican was the victim of injustice,” Mirandé concludes, noting, “Massive [Anglo] retaliation for crimes said to have been committed by Mexican bandits.”

As concerns Vasquez, Mirandé notes an assessment posited by Ernest R. May, in which he argues that Vasquez turned to cattle rustling and horse thieving in order to afford his “expensive tastes,” while he draws, in the main, from the pamphlets compiled by Truman and Beers (Mirandé does not mention Sawyer’s work), with Vasquez’ assertion that, "…My career grew out of the circumstances by which I was surrounded… A spirit of hatred and revenge took possession of me. I had numerous fights in defense of what I believed to be my rights and those of my countrymen… The white men heaped wrong on me in Monterey County… " Again, Mirandé highlights that Vasquez was a noted “ladies’ man,” and says, “Women were a determining force in his life.”

Adding to this inquiry, we must refer to Patricia Limerick’s work, Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (1987, New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc.). Here, Limerick’s history of the West offers relevant insights into the response of Vasquez to swift Anglo incursions, inciting the words of environmentalist Edward Abbey, who speaks of the tragedies brought upon the land by the Anglo-American rancher. Although speaking of a time after Vasquez, Abbey’s words highlight the direction that American society across the West was heading, many signs of which, no doubt, were evidenced upon central and southern California during Vasquez’ youth. Abbey lambasts the ranchers’ capacity to divide and transform the land, invite invasive non-native grasses and weeds, murder native animals “on sight… and then leans back and grins… and talks about how much he loves the American West.”

Limerick’s work is important in that she highlights previous Western historiography, for which, “Conquest basically involved the drawing of lines on a map.” Limerick describes a transition in Western studies, from Turner’s amorphous and ever-expanding frontier (as a process on American culture), into “a study of a place undergoing conquest and never fully escaping its consequences.” This, says Limerick, opens the West up as “an important meeting ground” of peoples, cultures, ethnicities, religions, and languages. Limerick notes, " Race relations parallel the distribution of property, the application of labor and capital to make the property productive, and the allocation of profit. Western history has been an ongoing competition for legitimacy— for the right to claim… the status of legitimate beneficiary of Western resources." This, Limerick says, has also included a competition for cultural dominance, into which, we can witness, the thrownness of Californios, gringos, and bandidos.

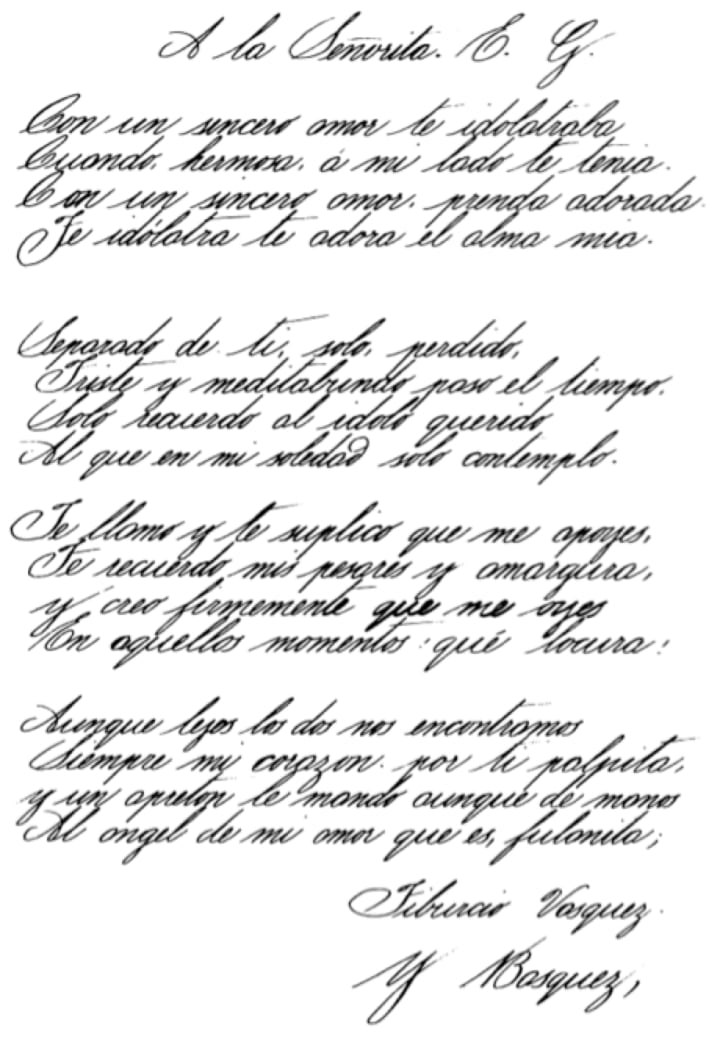

Figure 2 Tiburcio Vasquez, “A La Señorita E.G.” (circa 1874 - 1875)

Modern outlaw studies finally begin to fully address all of these tensions. William B. Secrest of Fresno compiled extensive news items and other source materials, often featuring Vasquez, from the mid-nineteenth century San Joaquin Valley and Coastal areas. From these, he has written a great deal about 19th century California law and justice in several works, notably Lawmen & Desperadoes (Spokane, WA: A.H. Clark Company, 1994), Dangerous Trails (Stillwater, OK: Barbed Wire Press, 1995), and California Desperadoes: Stories of Early California Outlaws in Their Own Words (Clovis, CA: Word Dancer Press, 2000). In one chapter from California Desperadoes, primary source materials and the reader are put to the work of re-constructing Vasquez’ life journey.

Secrest opens with two photos and a painting from California State Library. One is a photo of Vasquez beside his famous quote, “I always avoided bloodshed.” Another is a photo displaying items from Vasquez’ execution in San Jose, including a section of the rope and the tie he’d worn the day he was hanged beside Vasquez’ rosary beads and faith medallions. Third, we are shown a painting of the “adobe village by the sea,” Monterey in Alta California, from the days of Vasquez’ youth when “it housed many desperate characters.” Secrest then continues for thirty pages to incorporate a net of support sources, either primary or as background. We see a woodcut of “the bloody 1859 San Quentin prison break in which Vasquez was involved,” a letter (found in the saddlebag of a man, possibly Vasquez’ cousin, killed under suspicion of horse-theft) signed by Vasquez and addressed to his mother, and numerous mugshots and portraits of Vasquez associates, victims, or manhunters, who are often referenced through extended quotes.

What Secrest does well is to blend sources and viewpoints to make complex a previously two-dimensional caricature of Vasquez as a beloved terrorist. Secrest presents a Fresno Weekly Expositor report, “We could fill the entire local department of the paper this week with the thousand-and-one rumors floating about [regarding the hunt for Vasquez].” The paper laments that “Rumor has hanged two Mexican thieves near Kingston.” Secrest shows an image of a painting of Kingston, on the Kings River, featuring the town’s new bridge, which “had just been completed when [Vasquez’] outlaws crossed over to rob the village’s hotel and shops.” Such interwoven evidence delivers a sense of growth in the valley, and how Vasquez and his attacks preyed upon the sparse and isolated outposts that dotted the map of central and southern California. We can envision how word of mouth worked itself into a mass-furor that stalked the streets with hand weapons. We see the sporadic and inciting government interactions with the law through harsh words coupled with escalating offers of reward for capture that parallel the rise of Vasquez’ legend and popularity amongst dispossessed Californios.

It is the work of Secrest, along with the efforts of California bookseller and amateur historian J.E. “Jack” Reynolds, that allowed John Boessenecker, whose recent Bandido: The Life and Times of Tiburcio Vasquez (2010, Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press), to attempt a “full-length biography telling Tiburcio Vasquez’ true and complete story.” As noted by Lori Lee Wilson, Vasquez lived in a California “exceedingly rich in primary sources.” Echoing this statement, Boessenecker promises, “A great deal of information in this biography [that] has never been published before. Outlaws are by nature shadowy and secretive… Researching them is exceedingly difficult…” Boessenecker utilizes “hitherto unknown facts” concerning Vasquez’ youth obtained with help from remaining family and property records from Monterey, Santa Cruz, San Jose, Los Angeles, and mountainous San Benito County. Boessenecker references genealogical records to trace Vasquez and other prominent and supportive Californios.

The research of Boessenecker yields a fascinating and fresh understanding of the role that Vasquez played in California history, and how transitions therein dynamically played out upon his own life. “There was little in the gentle, fun-loving youth that would make anyone suspect he would turn into a fearsome outlaw,” states Boessenecker, a fact which can be seen in Vasquez’ family history. It is revealed that Vasquez’ great-grandfather was the first volunteer to join conquistador Juan Bautista de Anza’s trailblazing expedition from Northern Mexico to the “raw frontier” of Alta California, which the Spaniards hoped to secure against Russian or British settlement. Such actions as presidio-, pueblo-, and mission-building were intended to populate Alta California with Spanish citizens, while they ultimately had little impact upon the isolated landscape of the region, which was subject to violent Indian retaliation such as the Yuma Massacre of 1781. Boessenecker notes that the non-indigenous population of California had only reached about 4,000 by the year 1820. In the interim, “the Vasquez family had helped establish what would become two of the largest cities in the western United States,” those of San Francisco and San Jose. Indeed, Vasquez’s grandfather was the only literate citizen out of all nine of San Jose’s founding households.

Boessenecker’s emphasis on the military and civic service conducted by Vasquez’ ancestors, and their educated working-class roots, place an entirely new layer — and a clarifying one — onto the often-fuzzy image of Vasquez as a sexualized reactionary. Indeed, the picture is not as simple as even Steinbeck put it when he said, “Everybody thinks Vasquez was a kind of hero, when really he was just a thief.” With skill, painstaking research reflecting decades of pursuit, and a myriad of consulted sources, Boessenecker is finally able to flesh out a picture of Vasquez as a confident young horseman who, “like all Montereños, loved to watch ships come into harbor,” and who would grow into an enthusiastic social fandango attendee. This was finally to become his undoing as he increasingly found himself “among bandits” who frequented such dances, along with the unruly Anglo miners, mountain men, and gamblers who would often crash them.

The recent work of Zaragosa Vargas, Crucible of Struggle: A History of Mexican Americans from Colonial Times to the Present Era (New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2011), speaks of broadness in studies of Mexican Americans, both in matters of subject and in matters of scholarship. “The new generation of historians has broadened and developed our knowledge of Mexicans in the United States.” No doubt, Vargas has the tireless and even work of Secrest, Boessenecker, and Wilson in mind, and, to another degree, that of Mirandé. Like these authors, Vargas shares a concern that “there is a dearth of readable and comprehensive surveys of the history of persons of Mexican descent in the United States.” To this goal, his book stays true, providing a wide-ranging and ambitious report on the small and large stories that run the current of Mexican American history.

One of these stories for Vargas is that of Tiburcio Vasquez. Vargas, speaking to conditions faced by Vasquez in his Monterey youth, states, “Nativism made itself felt as Anglos lashed out at Mexicans… Land-hungry Americans dispossessed Mexicans of their lands… often accompanied by force. This Yankee xenophobia affected the Mexicans struggling to define themselves as U.S. citizens.” By utilizing “both legal and illegal means,” Americans swiftly illustrated to Mexicans that remained in the newly acquired states and territories that they were not liked, not considered, and not accepted, as illustrated by Vargas throughout early chapters of this work. Vargas contrasts the “[largely absent] unifying nationalistic sentiment among the Californios,” with “a fervent nationalism… in full force among Americans.” These are realities seen in the early life of Vasquez, and serve to explain the M.O. adopted by Vasquez and like criminals in conducting their crimes against Anglo travelers, couriers, and small towns. Not only this, such realities were seen in numerous conflicts across the Southwest at this time.

Vargas handles topics of Joaquin Murrieta and Tiburcio Vasquez by consulting a swath of classic and new histories of the west and of California, noting the practice and use of “blood contracts [between] American adventurers and outlaws to kill Indians at so much a head,” as well as historic land-grant displacement from “the most valuable agricultural and mineral lands in the state,” and how, in the case of Joaquin Murrieta, “a peaceful miner [could turn] into an outlaw [to avenge himself on all whites] after Americans stole his claim and attacked his family.” In these three examples we see outlaw as a tool of progress, capitalizing pioneer as the celebrated outlaw, and outlaw as a vengeful response to specific and widespread injustice. In other words, outlaws were either helpful, necessary, or contrary. The manner with which Vargas synthesizes such a large array of sources is not only engrossing but is also extremely acute. “Legends die hard…” says Vargas, even though, “many Mexican bandits often fell far short of their heroic images.”

No doubt this has something to do with a reality described by Wilson, "Nineteenth-century authors of yellow-covered books generally wrote hastily and usually published… under pen names… Publishers printed them hurriedly (printing errors were common) and on cheap paper; buyers paid little for them and did not treasure them but passed them on to friends… Very popular and often advertised in gold rush California newspapers, [such] books were sold… in San Francisco as well as trading posts near river crossings and at mining and lumbering camps." Just as the legend of Murrieta— through printed half-truths, rumor, and shared second-hand across dinner sets, be they wild or formal, throughout 19th century California— inspired Vasquez in his vengeful pursuits, so too has the legend of Vasquez inspired recurring waves of historians to take up the vengeful act of tracing world and national events back to their roots in the truth.

That outlaw historiography has reached a place of patient persistence— as exemplified by Boessenecker, Vargas, and Wilson— improves the likelihood that the legacy of bandidos will begin to give way to the realities of life faced by Californios, of whom Vasquez is but one example. “With its continuity restored,” asserts Limerick, “Western American history carries considerable significance for American history as a whole.” This, she reminds us, is because “conquest forms the historical bedrock of the whole nation.” All of the historians examined in this study work in different ways with their resources, and rely on a variety of interpretive skills to apply such material to the historical events presented by 19th century California. What becomes clear from a review of these works as a body of evidence is that transition in the American West was a layered affair, like tectonics, in which some stories were given a, perhaps undeserved, uplift of focus, while others were subducted beneath a comprehensive view by heavier weights of narrative.

Outlaw history provides an alternate view on Manifest Destiny, and one that would be welcome in a classroom setting. To give more dominance to the rebelliousness of the residents of the Southwest is to make the story of American expansion and dominance truly come alive, and with a more complete perspective. As Wilson points out, “Bandits never claimed what they did was right or good. Vigilantes and lynch mobs did.” Now, it seems, what is both right and good is to address the failings of dedicated representation conducted by past historians by drawing on new research that completes what was once begun by their hands, although sometimes unsteady. Though not searching for a Turnerian synthesis, certainly the field of history can hope to achieve an appreciation for the complex of layers involved with revealing the often forgotten details of the lives of southwestern Americans in the 19th century, many of whom have become legendary.

Bibliography:

—Abbey, Edward (1986, Jan.). "Even the Bad Guys Wear White Hats: Cowboys, Ranchers, and the Ruin of the West." Harper’s Magazine. pp. 51-55.

—Boessenecker, John. (2010). Bandido: The Life and Times of Tiburcio Vasquez. Norman, OK : University of Oklahoma Press.

—Hobsbawm, Eric J. (1959). Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries. New York, NY : W.W. Norton & Co., Inc.

—Limerick, Patricia N. (1987). The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West. New York, NY : W.W. Norton & Co., Inc.

—Mirandé, Alfred. (1987). Gringo Justice. Notre Dame : University of Notre Dame Press.

—Moreau, Joseph. (2003). Schoolbook Nation: Conflicts Over American History Textbooks from the Civil War to the Present. Ann Arbor, MI : The University of Michigan Press.

—Myers, John Myers. (1995). Bravos of the West. Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press. [Originally published as The Deaths of the Bravos. (1962). Boston, MA : Little, Brown).]

—Older, Fremont. (1940). Love Stories of Old California. New York : Coward-McCann Inc. pp. 242-253, 266-279.

—Secrest, William B. (2000). California Desperadoes: Stories of Early California Outlaws in Their Own Words. Clovis : Word Dancer Press.

—Sawyer, Eugene T. (1944). The Life and Career of Tiburcio Vasquez: The California Stage Robber and Murderer. Oakland, CA : Biobooks. Sullivan, Joseph A. Foreword.

—Turner, Frederick J. (1921). The Frontier in American History. New York, NY : Holt.

—Wilson, Lori Lee. (2011). The Joaquin Band: The History Behind the Legend. Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press.

—Vargas, Zaragosa. (2011). Crucible of Struggle: A History of Mexican Americans. New York : Oxford University Press.

Images:

— “Map of the United States.” Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, RG 233, http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2009/winter/gilman-map.html. Retrieved 21 Sept. 2012. Gilman, Ephraim. (1848).

— “A La Señorita E.G.” Sawyer, Eugene T. (1944). The Life and Career of Tiburcio Vasquez: The California Stage Robber and Murderer. Oakland, CA : Biobooks. Sullivan, Joseph A. Foreword. Translation found at Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. scvhistory.com/scvhistory/vasquez-alasenorita.htm. Retrieved 17 Sept. 2012. Vasquez, Tiburcio. (between 11 May 1874 – 19 Mar. 1875). “A La Señorita E.G.”

Films:

—Foreman, J. (Producer) & Huston, J. (Director). (1972). The Life & Times of Judge Roy Bean. (Motion Picture). United States : National General Pictures.

—MacBride, D.J. (Producer) & Jarmusch, J. (Director). (1995). Dead Man. (Motion Picture). United States : Miramax Films.

—Michelin, A. (Producer) & Godard, J-L. (Director). (1965). Alphaville, Une Étrange Aventure de Lemmy Caution. (Motion Picture). France : Athos Films.

See Also:

—Boessenecker, John. (1988). Badge and Buckshot: Lawlessness in Old California. Norman : University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 108-122.

—Boessenecker, John. (1999). Gold Dust and Gunsmoke: Tales of Gold Rush Outlaws, Gunfighters, Lawmen, and Vigilantes. New York, NY : John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

—Dunne, John Gregory. (1967). Delano: The Story of the California Grape Strike. Berkeley : University of California Press. pp 34-39.

—Enss, Chris. (2008). Outlaw Tales of California: True Stories of the Golden State’s Most Infamous Crooks, Culprits, and Cutthroats. Guilford : The Globe Pequot Press.

—Jackson, Joseph Henry. (1949). Bad Company: The Story of California’s Legendary and Actual Stage-Robbers, Bandits, Highwaymen and Outlaws from the Fifties to the Eighties. New York : Harcourt, Brace. Introduction, pp xii – xviii.

—Phillips, George Harwood. (1993). Indians and Intruders in Central California, 1769-1849. Norman : University of Oklahoma Press.

—Pitt, Leonard. (1966). The Decline of the Californios: A Social History of the Spanish Speaking, 1846-1890. Berkeley, CA : University of California Press.

— “Tiburcio Vasquez Trial and Murder Conviction at San Jose”. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. http://www.scvhistory.com/scvhistory/laws01161875.htm. Retrieved 17 Sept. 2012. “Vasquez: Conviction of the Robber of Murder in the First Degree”. Los Angeles : Los Angeles Weekly Star. (16 Jan. 1875). Page 4.

— “T.Vasquez: Letter from Varnum Westcott to Gov. Newton Booth”. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. http://www.scvhistory.com/scvhistory/vasquez-westcott.htm. Retrieved 17 Sept. 2012.

— “Abdon Leiva’s Version of Vasquez Gang Tres Pinos Massacre”. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. http://www.scvhistory.com/scvhistory/tsc052474.htm. Retrieved 17 Sept. 2012. “Vasquez’ Foulest Crime: Abdon Leiva’s Story of the Tres Pinos Massacre.” San Francisco : The Sunday Chronicle. (24 May 1874).

— “Execution of Vasquez!”. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. http://www.scvhistory.com/scvhistory/sdb031975a.htm. Retrieved 17 Sept. 2012. “The Bandit Vasquez”. Sacramento : The Daily Bee. (19 Mar. 1875).

— “Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey of California.” (1988) California Department of Parks and Recreation, Office of Historic Preservation. http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/5views/5views0.htm. Retrieved 17 Sept. 2012. Last modified 17 Nov. 2004. Accessed Dutschke “American Indians in California” and Pitti, Castaneda et. al. “Mexican Americans in California.”

—Martin, M. "Mexican American Studies: Bad Ban or Bad Class?" [Interview of Arizona school superintendent, John Huppenthal, re: Arizona Mexican-American Studies ban]. Tell Me More, 18 Jan. 2012. National Public Radio. Retrieved 23 Sept. 2012: <http://www.npr.org/2012/01/18/145397005/mexican-american-studies-bad-ban-or-bad-class>

—Stegmaier, M. J. & McCully, R. T. "Cartography, Politics— and Mischief." [Review of Ephraim Gilman’s 1848 Map of the US]. Prologue Magazine, Winter 2009, Vol. 41, No. 4. National Archives. Retrieved 12 Sept. 2012: <http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2009/winter/gilman-map.html>

About the Creator

Philip Canterbury

Storyteller and published historian crafting fiction and nonfiction.

2022 Vocal+ Fiction Awards Finalist [Chaos Along the Arroyo].

Top Story - October 2023 [All the Colorful Wildflowers].

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.