On the Muscle of Music

Tennessee Ernie Ford always follows too close behind me after we leave the gym. Credit where credit’s due, Ernie died in 1991 but his voice still sounds amazing.

As I hobble down two flights of stairs, triceps aching and the persistent pain returning to my lower back, Tennessee Ernie Ford sings into my ear all the way to the back lane exit.

Some people say a man is made outta mud

A poor man’s made outta muscle and blood.

He does this every time I work out too hard. I ignore him best I can, but he taunts me all the way down the street.

You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt.

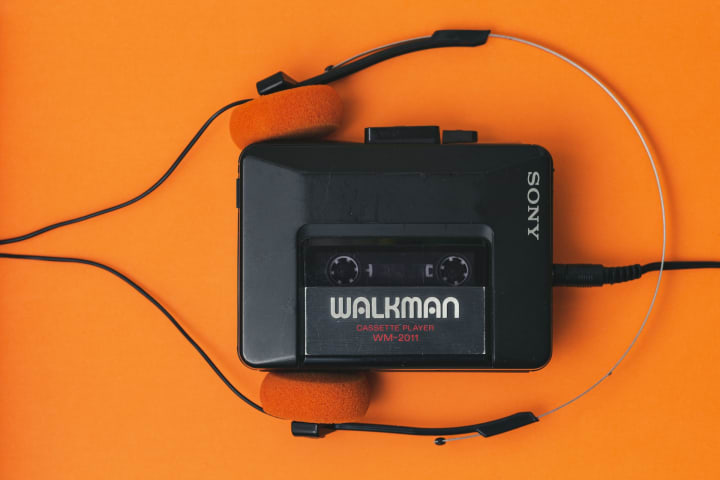

He sings the same old song every time I lift enough to know I’m gonna regret it. It didn’t used to be this way. I was an amateur bodybuilder in my teenage years, like my dad was in his. Back then, my imaginary gym buddies were Springsteen and Benatar urging me through my Sanyo cassette player to shake it off by Dancing in the Dark or running with the Shadows of the Night. But I’m not a teenager anymore and there’s a price to pay these days for pushing my limits.

He’s still singing when I turn the key in my door but, by now, I sure don’t feel like I have one fist of iron, the other of steel. More like two slabs of bruised meat hanging from hooks of rubber.

Ernie sings to me in the shower as I wash away the pain. He finally relents when I pour a whiskey and settle at my desk with something else to distract my mind, to paraphrase Dylan.

My whole life’s been like that. Lyrics buzzing round my head nearly every waking moment. My brain summoning uninvited lyrics from the back catalogue of my mind, playing on repeat, the song changing with my mood.

When I’m manic, Strummer calms me with Gangsterville. Billy Bragg has serenaded me with something from Worker’s Playtime when I’ve been heartbroken. When I’m feeling cool, Keith Richards keeps it going with Take It So Hard. Strange choice maybe, but you don’t argue with Keith.

When I’m melancholy, Bruce returns with How Can A Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live. I know it was originally a Blind Alfred Reed, tune but The Boss always sang it better.

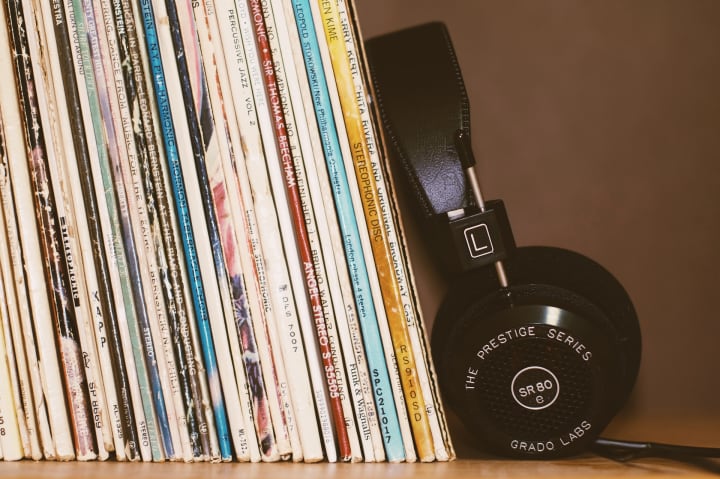

It’s no real secret why. Music was the connective tissue of my community growing up. We didn’t all have the same tastes. Almost none of us did. I was the only one who loved Buddy Holly the way Gene loved The Who. Ricky dug The Cars. Toni was into French cabaret by singers I wasn’t sophisticated enough to appreciate, no matter how patiently she tried. But, between classes, we’d endlessly debate who was the best, then press our case by swapping bootleg tapes.

We didn’t have much, but we had enough pocket money to buy a record or CD every couple weeks and we had older bothers whose collections we raid long enough to commit their platters to BASF cassette.

By the time I left high school, I had a respectable collection of vinyl scavenged mostly from flea markets and discount racks. It broke my heart when I had to sell it to pay rent when I hit on hard times in ’92.

When the ’90s fashion revival hit a few years back, it was accompanied by a wealth of think pieces that tried to zero in on the definitive traits of Generation X. Those articles were, on the whole, bullshit.

We were told we were the cynical generation. If you had to live through 1989 as a young man, you would be too. Apparently, we were also slackers. News to those of us who skipped school to protest apartheid, Tiananmen Square, and a wilfully lax response to the AIDS crisis. There also weren’t a whole lot of yuppies on my side of town.

It was our relationship to music that really defined us. In the schoolyard, in the clubs, even on the sidelines of a protest, we found time to focus on the music that shaped our lives and the way we saw them.

Springsteen once said hearing Like A Rolling Stone for the first time “kicked open the door to your mind” and he was right.

In the days of mixtape seduction, I gave a girl a copy of Darkness on the Edge of Town. She gave me Talking to the Taxman About Poetry in return, which turned me on to socialism.

No small wonder, then, that my first paying gig as a journalist was as a reviewer for a street press music magazine. Still the best job I ever had. I’ve written better things in bigger places but there’s something sublime about Ted Nugent’s record label going to the effort of sending me a review copy of Spirit of the Wild just so I could shit on it in print.

Even when I moved on to political speechwriting, I’d ‘sign’ even speech by sneaking unattributed nods to song lyrics in the script. I’d have a particularly conservative politician reference Woody Guthrie and The Clash, figuring they’d never listen to them.

I pushed it a little too far when I decided to insert as many song titles as possible from Roxy Music’s greatest hits album, More than This, into a single speech. I worked in Out of the Blue, Street Life, Let’s Stick Together, Same Old Scene, More Than This, These Foolish Things, and even Avalon, but conceded defeat when it came to Love Is the Drug.

I spent the next week living in fear of being found out when, a split second after hitting send on the email, I had a horrible thought:

This seems like the kind of guy who would be a big fan of Roxy Music.

If he ever twigged, he never let on.

But what was I supposed to do? Music was everything. Music gave us thought. It gave us hope. Gave us life, and the power to Choose Life.

That sound in our head — those songs — are a reminder to keep the choices and the promises of my younger years alive.

I can’t be the only one.

There must be millions of us for whom the music of our youth is the prism of our perception. Music not so much of the people, but for the people. Forever.

If you’ve read this far, maybe you’re one of them.

And if you’re the guy who paid a dishevelled punk in a flannel shirt five bucks for the red vinyl limited edition of U2’s Under A Blood Red sky at a flea market in 1992, I have one request.

May I please have it back?

About the Creator

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.